For decades in the second half of the 20th century, Mexico City was dismissed as one of the most dysfunctional cities in the Americas, struggling to cope with a population edging past 20 million and an unfortunate geological site. Founded by the Aztecs in 1325 on an island on Lake Texcoco, the city had been built on soft soil which, as well as subsiding on a regular basis, was vulnerable to flooding and earthquakes. As other cities such as Buenos Aires and Rio flourished, constructing ever-higher skyscrapers, Mexico City had to be content with sprawling outwards, creating a conurbation that, futurists warned, was spiraling out of control.

Fast-forward to 2015, and how things have changed. The city is now a beacon of urban-design brilliance and all the world’s architects want a slice of the action. As architect Zaha Hadid observes, “Mexico City has the most amazing buildings – from Luis Barragán’s masterpieces to Félix Candela’s ‘shell’ building to really strong Brutalist and Mid-Century Modern structures.” In the past few decades, too, the city has undergone a renaissance, with a new generation of buildings by high-tech architects and designers. As well as a center of finance, Mexico City has become a hub for art, design and creativity, with an economy the size of Peru’s.

“Construction started to boom here even when other parts of the world were in recession,” says architect Ezequiel Farca, who works both in Mexico City and Los Angeles. “Architecture and design are going through a great phase now and are poetic and free enough to create something bold and full of imagination. Young architects are inspired by the Mexican masters, which you can see through their use of color, proportion and building techniques. At the same time there is a revival of furniture design and a greater appreciation for design icons such as Clara Porset and William Spratling.”

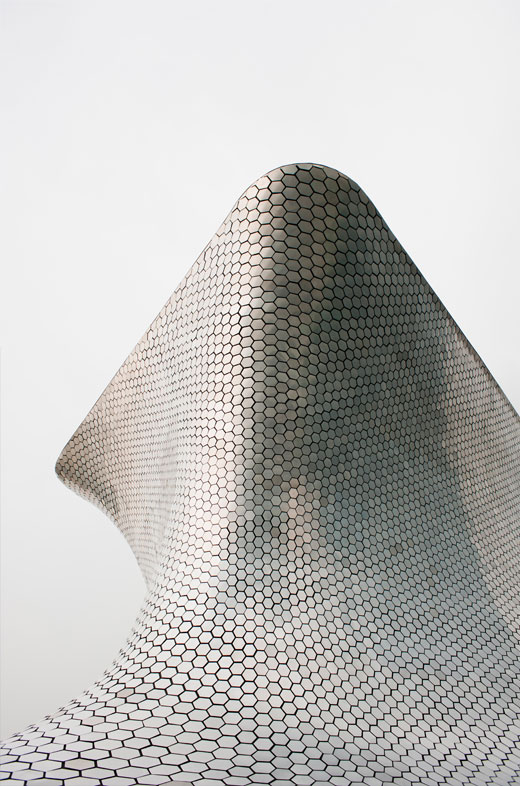

In the past ten years, not only have charming old buildings been given new life, but a mass of hotels, restaurants and stores have sprung up alongside the city’s 150 museums. New landmarks include the Soumaya Museum, designed by Fernando Romero, with its sinuous, futuristic form made of metallic, hexagonal reflective plates to house an art collection amassed by telecoms billionaire Carlos Slim Helú. Next door sits the Museo Jumex, designed by British architect David Chipperfield for fruit-juice giant Grupo Jumex’s contemporary art collection. Also winning admirers is the Chopo Museum, whose glorious extension by Enrique Norten of TEN Arquitectos is an addition to an original 1902 building by Bruno Möhring.

Working alongside local architects are a slew of big international names. British starchitect Norman Foster is coming to town to build, with local hero Fernando Romero, a much-needed new international airport. Argentinian architect César Pelli, who designed the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, came to Mexico City to build The St. Regis Hotel Tower in 2008, and Richard Meier is busy designing the Reforma Towers, a mixed-use project on main thoroughfare Paseo de la Reforma.

“Thanks to the constant relationship between Europe, North America and Mexico, architects and designers have found Mexico the most beautiful place to express their individuality and have constantly added to the city,” says Emmanuel Picault, a Frenchman who settled in the city when he was 18. “There is still a feeling of liberty and joy that brings people here.”

All of these projects highlight the vibrancy of Mexico City today. But they also add a new layer to a metropolis that has one of the most multifaceted histories of any city in the Americas. This is a city that has reinvented itself many times since the days of Montezuma, when its population was already a great deal larger than that of London.

When Hernán Cortés and his successors began work on a new colonial capital, it was the ruins of Aztec temples and palaces that they used as foundations for their own buildings. Cortés himself ordered the construction of the Metropolitan Cathedral – the oldest in Latin America – alongside the ruins of the Aztec Templo Mayor. Centuries later, the architects of “New Spain” continually sought to layer their own designs over those of previous civilizations. Although the later modernizers of the 19th century adopted Spanish and European architectural styles – with influences from Gothic architecture, Spanish neoclassicism and Hispano-Moorish motifs – they were equally inspired by the local mestizo population, creating a style of architecture that was uniquely Mexican.

Walk around Mexico City today and one can observe the process of cultural fusion that has helped to shape the capital. In some parts, such as Colonia Roma, Condesa and Juárez, it is possible to see the French influence of the 19th century and again when Art Nouveau emerged, French-trained architects ruled, and villas sprang up all over the more desirable suburbs.

In other parts, exciting 20th-century architecture dominates: buildings that were created after the end of the revolution in 1920, when a process of re-evaluation began. While some architects, such as the country’s greatest Modernist Luis Barragán, found inspiration in the simple purity of Mexican adobe houses, others looked to Europeans such as Le Corbusier. By combining both – the pure geometry of Modernism and the organic warmth and character of traditional Mexican architecture – local architects created a regional fusion with a rich personality all of its own.

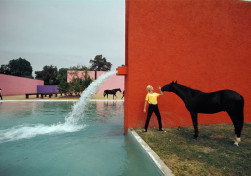

If there is one architect whose legacy looms the largest in the city, it is Barragán, who died in 1988. His warm, sensitive but contemporary buildings – among the few Modernist examples loved by traditionalists, too – are full of vivid color, rich textures and integrated gardens and fountains. The ranch house that he designed for Folke Egerström in San Cristóbal is considered one of the greatest delights of 20th-century architecture and a celebration of both the architect’s and client’s love of horses. Barragán’s Chapel and Convent in Tlálpan are a hymn to light and serenity, while his Satellite City Towers on the Querétaro Highway are a much-loved public landmark. The architect’s own house in Tacubaya is open to the public and an essential stop on any architectural tour of the city.

As well as creating a distinctive architectural lexicon with his own buildings, Barragán also inspired a generation of local architects. They included the great Ricardo Legorreta, who shared his passion for color and texture expressed in vivid, modern forms, and designers such as Félix Candela and Teodoro González de León, who injected Mexican architecture and design with an energy, dynamism and ambition not seen before.

There are plenty of other individualists, too, who have imparted their own specific style on the landscape. Agustin Hernández, for example, takes inspiration from the pyramids, patios and ziggurats of Mayan cities, inventing houses that look like concrete spaceships on slender supporting pillars, hovering over the hills around Mexico City. Adamo Boari and Federico Mariscal created the Palacio de Bellas Artes in the 1930s, inspired by a mixture of neoclassical, Art Deco and Art Nouveau design and graced with murals by Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros. And Juan O’Gorman built a home-cum-studio for Rivera and Frida Kahlo, designed in an early Modernist style but full of color, light and drama. The list goes on.

“We love mystery and surprises,” Ricardo Legorreta once said. “Even in our way of being we are quite mysterious. We say we are a simple people but we are extremely complicated. The depth of the architecture we create is the depth of Mexico and its people.”

Dominic Bradbury writes on design and architecture. His latest book,

Mid-Century Modern Complete, is published by Thames & Hudson/Abrams

Your address: The St. Regis Mexico City

Images: René Burri/Magnum Photos, Adam Wiseman, Inigo Bujedo Aguirre/Viewpictures.co.uk