It’s those beautiful artists’ impressions of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan that make people say so many unjust things about Mexico City. The emerald-hued lakes, the slender causeways, the story of Montezuma, enthroned in his feathery splendor, warmly greeting Hernán Cortés – only to be betrayed by the duplicitous conquistador, cut down in his prime, and the Aztec empire crushed.

It’s true that when you fly into Benito Juárez International airport, you can’t help lamenting that such a wonder has been buried beneath millions of tons of concrete, and a sprawl of houses, apartment blocks, shanty towns and suburbs that shatters the human scale while housing 20 million human beings, or more – no one really knows. Nevertheless, Mexico City, or DF (pronounced day-efay, standing for Distrito Federal) as everyone calls it, is not the impenetrable, car-dependent maze of modern myth. Indeed, a pleasant introduction to the center, and one that subverts several stereotypes about the Mexican capital, is to walk it, slowly, calmly, flaneurishly, from Aztec heart to contemporary barrio.

I begin where you have to begin: standing at the center of the Zócalo, the vast main square; officially the Plaza de la Constitución, though no one ever calls it that. This is where Mexicans protest and march, celebrate and stroll, kiss and tell. The Spanish included grand plazas in all the major cities they built over pre-Columbian settlements, and one has to suspect that the Zócalo is one of the biggest of these because it had to symbolically bury the majesty of what stood here before.

Parades and expos occasionally invade the plaza, but today there are only strolling locals, a statue of Cuauhtémoc, the last native ruler of the city, and a massive Mexican flag, unfurling in the warm morning breeze.

A magnificent vestige of the pre-Hispanic city lies at the plaza’s northeastern corner. The Aztec Templo Mayor was Tenochtitlan’s sacred hub, continually expanded over two centuries by the city’s rulers. The archaeological site is no mere pile of stones, but rises, strangely, magnificently, with serpents greeting you as you turn a corner, and daubs of the red, blue and yellow paint that once glowed under the highland sky. The temple was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, sun god and bringer of war, and Tlaloc, the rain god and source of fertility. Arid death and liquid life.

Right next door, the vast Metropolitan Cathedral is the biggest cathedral in the Americas. It’s a squat, hulking edifice, designed to crush any memory of what might have been worshipped here before the arrival of Cortés and his Christian soldiers. A medley of baroque, neoclassical and Spanish churrigueresque (elaborate stucco ornamentation) elements, it too has been built and rebuilt several times over the centuries.

Before exiting the Zócalo I duck into the Palacio Nacional to see Diego Rivera’s murals, which decorate the stairwell and the middle story of the central courtyard. The panoramic piece, titled México a través de los Siglos (Mexico Through the Centuries), conflates the dramatic history of this great nation into what looks at first glance like an insane group photograph – with Quetzalcoatl (the plumed serpent) rubbing shoulders with Zapata’s revolutionaries, who are in turn looking down on the dastardly inquisitors, Hidalgo the liberation hero, five-times president Benito Juárez, and many other assorted great and good, plus Rivera’s wife, Frida Kahlo, and Karl Marx, helpfully giving directions to the massed proles.

I’m dizzy with names and blinded by colors by the time I get back outside. I grab breakfast at the nearby Café de Tacuba. This handsome institution, all tiled walls and white-aproned waitresses, has been serving good coffee and sublime tamales – chicken-filled corn wraps served with spicy sauce – since 1912. It also lent its name to a well-known Mexican pop group.

I continue west along Calle de Tacuba, which lies along the axis of one of the lake-city’s original causeways. It’s an elegant part of the city, with a distinctly European feel, though I occasionally arrive at hectic, aromatic corners where streetfood vendors are whipping up filled tortillas and crispy tacos for the time-poor traders and political aides who work in these parts.

Billionaire investor and philanthropist Carlos Slim has been throwing money at the city center, and many facades look new or very well polished. Edifices that were little more than warehouses or squats have been taken over as office space, work-live accommodation and nightspots. Prone to seismic activity, Mexico City is a mid-rise city, though I occasionally catch glimpses of the lofty, 597ft, 44-story Torre Latinoamericana, a glass and steel quake-proof landmark that was once the tallest building in Latin America.

My next stop, in the shadow of the Torre, is the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Built during the 1876-1911 Porfiriato – the modernizing, if sometimes brutal, regime of Porfirio Díaz – and facing the Alameda Central, it’s one of Mexico City’s most beautiful palaces. Begun in 1904 and overseen by Italian architect Adamo Boari, a fan of neoclassical and art nouveau lines, its construction was interrupted by subsidence issues and then the Mexican Revolution. It was completed by Mexican architect Federico Mariscal in the 1930s, with the interior leaning towards the then-fashionable art deco style.

The three expansive floors of Mexican and international art merit a day or more, but I limit myself to viewing pieces by Rufino Tamayo, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, including the celebrated El hombre en el cruce de caminos (Man at the Crossroads), originally commissioned for New York’s Rockefeller Center. The Rockefellers had the original destroyed because of its anti-capitalist themes, but Rivera recreated the work here in 1934.

The Alameda Central is one of relatively few green spaces in the Cuauhtémoc quarter. Created by Viceroy Luis de Velasco at the end of the 16th century, and enlivened by paved footpaths, decorative fountains and statues, it occupies what was once an Aztec marketplace. The name comes from álamo, Spanish for poplar tree.

These elegant gardens provide a natural border between old, romantic DF and the Paseo de la Reforma, the throbbing heart of modern Mexico’s economy. Skyscrapers loom over every block of the Reforma, including impressive landmarks such as the Torre Mayor, owned by George Soros, Torre HSBC, the Angel of Independence monument and César Pelli’s sleek Torre Libertad, home of The St. Regis Mexico City.

I make a slight detour to the Plaza de la República to admire the Monument to the Revolution, a towering neoclassical triumphal arch that doubles as a mausoleum for several heroes of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, including Francisco “Pancho” Villa.

A hop away at Calle Antonio Caso No. 58, is the Cantina La Castellana. Established in 1892, it’s one of a dozen or so traditional cantinas left in the ever-evolving, fad-hungry capital. It has 13 big TV screens, six of them showing a soporific, scoreless Mexican football match, six an overacted soap opera, and one a grisly news bulletin. There’s a cheap buffet, into which the clientele of working class men is diving with gusto, filling soup bowls and piling up plates of potato, meat and beans. I opt for the daily special, which today is the very Mexican chamorro enchilado al horno – oven-baked, chilli-peppered pig’s leg – superb with a well-iced bottle of beer.

Buzzing, cozy, laid-back, this cantina, like all the best ones, is timeless. Some of the men are playing dominoes. Several are just having beers and botanas – salty snacks. Mariachis sometimes drop by, usually in the afternoon, not because they think tourists will reward them but because they are appreciated here. La Castellana also has some cultural cred: past visitors included author Renato Leduc, who hung out with Antonin Artaud in Montparnasse, and songwriter Álvaro Carrillo, who composed more than 300 songs, most of them romantic boleros. Poet Pablo Neruda, Communist activist and essayist José Revueltas and poet Efraín Huerta were also habitués.

After lunch – the match still at zero-zero, the dominoes still clacking – I’m back on to Reforma, which is busy with lunchtime traffic. The thoroughfare was commissioned by Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I to seal his authority on the city after overthrowing Benito Juárez in 1864. Designer Ferdinand von Rosenzweig’s intention was to grace the imperial capital with a grand boulevard equal in grandeur to the Ringstrasse in Vienna. It would also serve as direct route to – and an imposing sightline for – the Castillo de Chapultepec, the imperial residence.

Reforma these days feels very modern, with police zipping along the wide pavements on Segways, and the mainly modern and functionalist architecture and bank and brokerage HQs attesting to the power of commerce rather than conquering viceroys. After the narrow grid of the old city, it’s good to see some sky, too. I don’t generally do shopping, but I decide to stop briefly at Fonart at Paseo de la Reforma No. 116. Buying local handicrafts is a minefield for travelers, but these government-run, fixed-price outlets are a joy: superlative textiles and art are on display and browsing is more like a museum visit rather than mere retail.

The Altar a la Patria, six white marble columns honoring six teenage cadets who died in the 1846-8 Mexican-American War, marks the entrance to the Bosque de Chapultepec – a name that means Chapultepec Wood but doesn’t quite capture the magnitude of this verdant megaspace. Spreading over some 1,695 acres, it’s one of the biggest city parks in the world. Made especially delightful by its hilly contours, it invites you to breathe deeply, take in a view over DF and enjoy a few minutes of silence – well, subdued traffic hum, anyway. Native carpenter birds and hummingbirds sing and tweet, and the park is a refuge for migratory birds from Canada and the U.S., including the red-tailed hawk and Harris’s hawk. Dozens of tree species provide shade, including the Montezuma bald cypress, Mexico’s national tree.

Overlooking all this is the Castillo de Chapultepec, accessed via a winding, gently inclined road. A sacred spot for the Aztecs, the mansion we see now is a reminder of Mexico’s bygone aristocracy. It was begun in 1775 but not completed until after independence, when it served as the national military academy. When Emperor Maximilian and Empress Carlota arrived in 1864, they gave it a regal refurbishment and it was the presidential pad until 1939 when it was converted into the Museo Nacional de Historia.

The displays chronicle the periods from the rise of colonial Nueva España to the Mexican Revolution. Even more impressive than the sumptuously furnished salons, swords and banners are the dramatic interpretations of Mexican history by muralists Juan O’Gorman and David Siqueiros. Huge, overpowering and full of the everyday chaos of humanity, Mexican mural art enfolds and moves the viewer in a way sedate, framed gallery art can’t. I leave the museum feeling uplifted as well as informed.

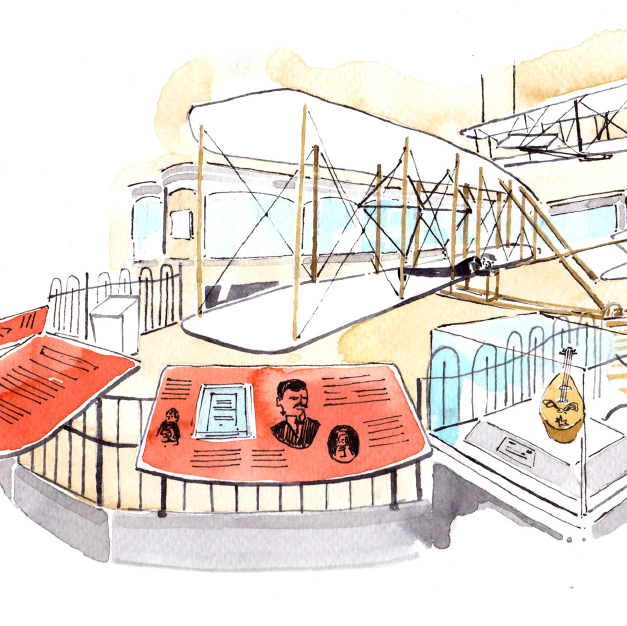

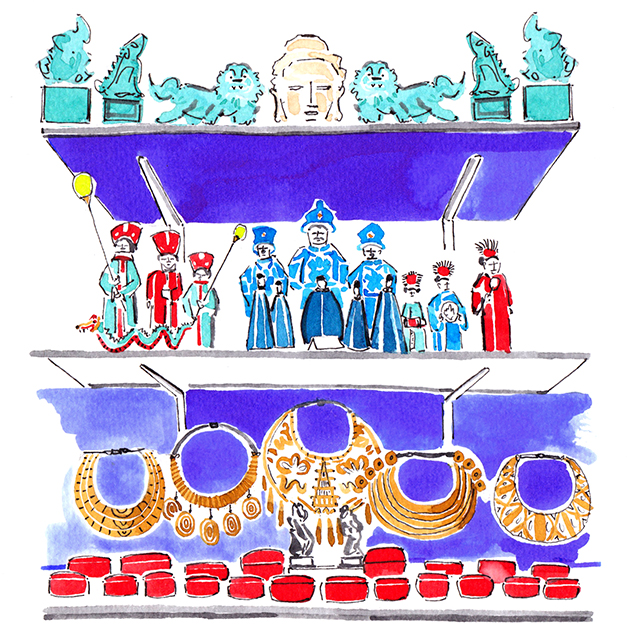

It’s only a 20-minute walk to my final cultural pit stop, one of the world’s greatest museums. This is only my second visit to the Museo Nacional de Antropología but I know what not to do: try to take in 23 rooms and more than 4,000 years of pre-Columbian art and culture in a single sweep. Instead I focus on a couple of eras. The Olmecs – the first major civilization in Mexico, present from the 16th to the fifth centuries BCE – tend to get less attention than the Aztec and Maya but, as the colossal heads, clay dolls, vases and figures on show demonstrate, theirs was a bold and brilliant culture.

The museum’s building is an artwork in its own right. The umbrella-shaped edifice was designed by three visionary Mexican architects, and when it opened in 1964, the soft, tropical brutalism was considered audacious. The exhibition halls surround a courtyard and a large pond so that as you move between rooms you find yourself suddenly in a serene, airier space. It readies the spirit for the next bout of learning and awe.

My second specialism for the day is the Maya. While I’d seen many of the magnificent sites around Yucatán, it filled in gaps to see the altars and artworks shipped from the peninsula to be exhibited in the capital. Indeed, when it comes to everything in sprawling, multi-faceted Mexico – from food to art to music to commerce – in the end all roads lead to DF. The capital sucks in energy and creativity and concentrates it here.

The sun is slipping away and the gardens around the museum are cooling down, breathing out their evening perfumes. I walk slowly towards the north, exiting into Polanco – Mexico City’s most upscale neighborhood. As barrios go, compared with the shabby chic of Condesa and the hip, emerging buzz of Roma, Polanco is sedate and civilized. Which is a relief – because after a longish walk (only about six miles but lots of zigzagging and art-filled corridors along the way), I need some leafy luxury and lounging.

Polanco was originally a hacienda (rural estate) and then a suburb until the early 20th century, when mansions began to pop up surrounded by old-growth trees and high walls. First retail moved in and then, from the Seventies on, companies fed up with the gritty flavor of the Zona Rosa relocated here. Embassies, restaurants and boutiques followed, and sleek towers were erected to house their well-heeled employees. As a result, Polanco has also become one of the city’s best spots for high-end dining.

Before I partake, I need a drink. Jules Basement prides itself on being Mexico City’s first speakeasy. The term means very little nowadays but there’s still something exciting about passing through a big fridge door and some rubber drapes to find yourself in a shimmering space – all black, white and silver: cool in the shivery sense – with cocktail tables inspired by Mexican skull art. A bit industrial, very theatrical, and somehow very Mex-urban, it’s a good spot for a pre-dinner cocktail. I have a mescal-based Negroni that wipes out the day’s toils and then a cool artisanal beer.

My last stop is a place I first read about in the influential S. Pellegrino World’s 50 Best Restaurants listings. Polanco boasts three top-rated places within a few blocks. Quintonil and Biko are two, but I opt for Pujol, where El Bulli-inspired chef Enrique Olvera specializes in refined versions of native cuisine. He cooks with ant larvae and grasshoppers and, in a nod to local streetfood culture, prepares one dessert with a 20-day-old banana.

The tasting menu is a series of taste volleys, from fried pork to delicate sweetbreads to a succulent tamal (closing the circle I’d begun at breakfast) to a range of moles – Mexican sauces, some with chocolate and sweet spices – and a glass of Baja Cal white. The meal is deeply indigenous, and as exquisite on the palate as anything the Old World has to offer. A DF mini-banquet. A megalopolitan treat. A fitting finale to one of the world’s great city walks.

Your address: The St. Regis Mexico City