Serge Obolensky’s life reads like a work of fiction. There is a fairy-tale beginning: he was born a Russian prince and married a princess. There is adventure: for our prince was brave as well as handsome… a dashing young cavalry officer in the First World War, he escaped from the Bolsheviks with a price on his head, while in the Second World War he became an American commando who parachuted into Nazi-occupied Europe. There is Gatsby-era glamor: the second Princess Obolensky was a renowned American heiress. And a dash of cocktail lore: legend has it that he inspired the creation of the Bloody Mary in the King Cole Bar of The St. Regis New York. This heady concoction sounds too extraordinary to be true, but life can be stranger than fiction, as Obolensky well knew.

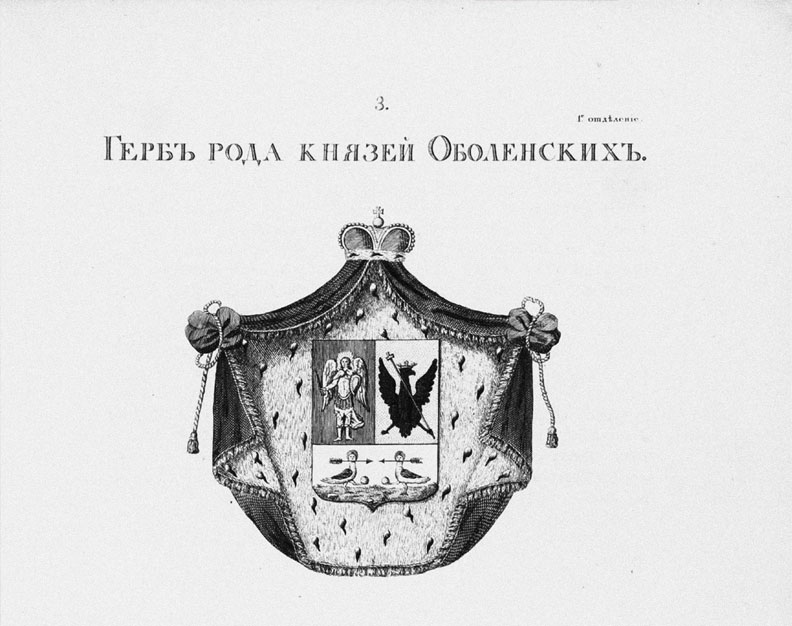

Let us begin, though, at the beginning, in 1890, when Serge Obolensky was born, the heir to one of Russia’s grandest aristocratic families. Decades later, in his memoirs, he recalled the vanished country of his youth: the winter sleigh-rides to his grandmother’s palace in St. Petersburg, the summers spent on his parents’ vast estates, the fun of Countess Tolstoy’s costume ball. And there were trips abroad, for like other wealthy Russians, the Obolenskys travelled widely – visiting Paris, or fashionable belle époque resorts such as San Sebastian and Biarritz.

Obolensky’s education was rounded off at Oxford, England, where he played polo and joined the exclusive Bullingdon Club, while out of term he was a hit with London’s leading hostesses. Many of the friendships that Obolensky formed at this time would be important in his later life.But in both London and St. Petersburg, he was experiencing two great imperial capitals on the eve of enormous change. In London he recalled “an air of massive elegance and leisure all but inconceivable in any later period. I believe I saw the end of it… the mellow grandeur of the Edwardian age.” In Russia, revolution was about to bring the Obolenskys’ world crashing around them.

Obolensky called his memoirs One Man in His Time, but what is remarkable is his knack of being in the right place, if not at the right time, then at a fascinating time. Even with the advent of war, when he joined the crack Chevalier Guards regiment, he enjoyed one final “cavalryman’s paradise”, as his regiment covered the Russian army’s slow retreat in “a form of warfare that will never come again”, as the age-old hegemony of mounted soldiery gave way to an era of trenches and tanks.

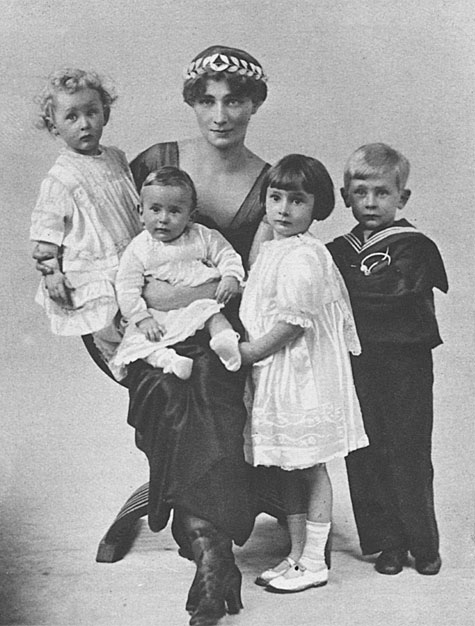

If Obolensky’s recollections make the war seem almost fun – more fun than the trenches, certainly – it is worth noting that he also won the St. Andrew’s Cross for valor three times. Meanwhile, like many of his class, he sensed the coming crisis as the vast Empire of all Russias began to fracture under the strain of war. In 1916 he married Princess Catherine Yurievskaya, the daughter of Tsar Alexander II and his aristocratic mistress (and later wife). Catherine had grown up in France and wasn’t close to the current Tsar, Nicholas II; nor was Serge. Yet their lives, like that of millions of Russians, would be turned upside down when Nicholas led the Romanov dynasty and the nation into the abyss.

With the onset of the Revolution, the big cities were plunged into chaos, and Serge and Catherine joined an aristocratic exodus south to the Crimea, that Riviera-like coastline of palaces and villas he’d known well as a child. There he joined the “White” forces fighting the Bolshevik “Reds”, but as the horrors of civil war unfolded, even a battle-hardened Obolensky found the mix of horror and beauty “sickening... the total destruction of a childhood memory”.

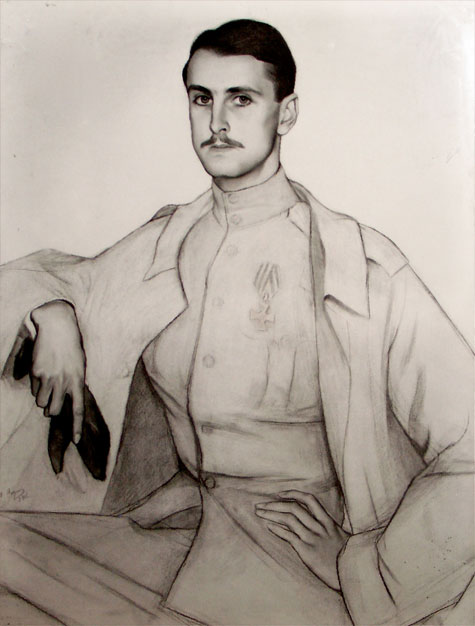

Around this time the society painter Savely Sorine drew a sketch of Obolensky, capturing something serious about the eyes as well as the elegance of the young officer. This portrait would eventually wind up in Obolensky’s apartment in Manhattan, where in 1970 he was photographed alongside it for a New York Times feature headlined: “Serge Obolensky: a Society Legend at 80”. All those years later, he is recognizably the same man. But just like its subject, the sketch had gone through some dramas along the way. It acquired a spray of bullet holes when the Reds shot up Catherine’s palace in Yalta. Then it was displayed with the inscription, “Serge Obolensky, Wanted, Dead or Alive”, until Sorine bribed a guard with three roubles to let him take down the sketch and then smuggled it out of Russia. More importantly, the artist also spirited Catherine out of her ransacked palace and into hiding. Husband and wife would be reunited in Moscow, both in disguise, having endured hardship and danger. They eventually escaped to London, via Vienna and then Bern, where Serge could access the $200,000 he had cunningly squirreled out of Russia into Swiss bank accounts.

A tiny fraction of the Obolensky fortune, this was still considerably more than many exiles managed to escape with. During the 1920s former Russian debutantes worked as cabaret dancers in Shanghai, while one Romanov prince eked out a living as a Paris taxi driver. Many White Russians never quite got their heads around these reversals of fortune, their grief at what had been left behind or the sorrow of exile. Presumably Serge Obolensky felt all of the above keenly. But just as impressive as his derring-do flight from Russia was his ability to shed any Russian might-have-beens and get on with his life. “He never looked back,” his son Ivan Obolensky agrees. “He had a resilience, an ability to hang on to happy memories, but always to look forward.”

Serge’s father had intended him to be a modern agriculturalist farming the vast family estates. Now the estates were gone. What remained, however, was Obolensky’s extraordinary charm, surely key to his remarkable ability to land on his feet. People liked Serge Obolensky. This had probably saved his life in Russia, where he had been aided by a former employee, an old shoemaker of his acquaintance, and a nurse he’d never met before, all at considerable risk to their own lives. This quality would serve him well throughout his life. “He had such ease,” his son recalls, while his secretary told the New York Times, “He could charm the birds from the trees.” And looking at the photographs of him whirling celebrated beauties around the dance-floor, it is clear that women adored Serge Obolensky. And he certainly married well – as princes in stories are meant to.

On escaping Russia, Serge and Catherine lived increasingly separate lives and then divorced, amicably. Serge moved into the flat of his cousin, Prince Felix Yusapov (famous as one of the men who murdered Rasputin) in London’s Knightsbridge, and then after an ill-starred trip selling farming equipment in Australia, settled down to the prosperous, bowler-hatted life of the London stockbroker. Then one night he went to a costume ball and danced with Alice Astor. He was dressed as a Cossack. She was wearing a Chinese dress and a necklace from the tomb of Tutankhamun. They promptly fell in love.

Alice’s father, John Jacob Astor IV – one of the richest men in America – had built New York’s celebrated St. Regis Hotel. He went down with the Titanic, but Alice’s mother Ava, the formidable Lady Ribblesdale, was very much alive and strongly opposed to her daughter marrying “an impoverished Russian prince”. However, when Alice came of age, she got her way, and their marriage was the wedding of the London Season in 1924. Or rather weddings, for there were three: an Anglican one at the Savoy Chapel, a civil ceremony, and then an Orthodox one at the Russian Church. Alice’s British cousin, Viscount Astor, gave away the bride, while Serge’s old Oxford friend Prince Paul of Serbia was best man. They honeymooned in Deauville, France, and thus began their luxe, but peripatetic, married life spent on ocean liners and yachts, in grand hotels or at their spectacular homes in London and upstate New York.

“Nothing world-shaking happened – which was pleasant for a change,” Obolensky quipped of this time. Looking back, their decade together was “a haze of golden memories... I enjoyed it enormously.” But one senses a quickening of the pulse when, after Alice filed for divorce in 1932, Obolensky started working in earnest for her brother, Vincent Astor, who tasked him with restoring the luster of The St. Regis New York, which had just returned to family ownership. “Vincent suggested that I look things over and make my suggestions,” he explained, “as I had lived much of my life in the best hotels of Europe. He made me a sort of general consultant, promotion man, and trouble-shooter… This is how I started in the hotel business. I found it captivating and a challenge.”

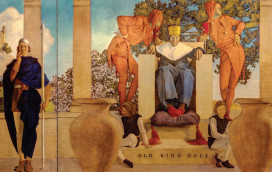

Obolensky turned out to have a genius for hotel-keeping. When Obolensky took over The St. Regis, he says, “the old-fashioned lobbies were dark and uninviting. There were no wine cellars, and the food was conventional. Yet the building was an architectural masterpiece. When Colonel John Jacob Astor IV had built it, he’d wanted to make it the great luxury hotel of the New World.” Working with the decorator Anne “Nanny” Tiffany (and “various impoverished but brilliant Russians”, as Ivan Obolensky recalls) Serge and Vincent set about updating the public areas. The roof garden soon became a “Viennese fête champêtre”; a rink was installed for ice shows; and the hotel acquired a Russian-themed nightclub, the Maisonette Russe, complete with a gypsy orchestra and a chef who had cooked for the Tsar. (He was a friend of Vassily, the Obolensky family chef who’d escaped Russia with Serge.) Most notably, the Maxfield Parrish painting of Old King Cole (from another old Astor property, the Knickerbocker Hotel) became the centerpiece of the new bar. It was here, as legend has it, that Obolensky made his contribution to the creation of the Bloody Mary. The story goes that he asked barman Fernand Petiot to spice up his tomato and vodka cocktail – thus introducing the dash of Tabasco.

But Obolensky’s strategy went way beyond hotting up the cocktails and refreshing the décor. A great metropolitan hotel is part of the swim and flow of a city. Serge knew this instinctively, and he knew how to deliver it – by inviting his fancy friends around. Time and again the society pages of the era contain an item headlined “Prince Obolensky hosts” – usually describing a dinner for a Vanderbilt, a Whitney or visiting European royalty. Obolensky was clearly very social, but these meticulously placed stories also show a hotel man hard at work promoting his hotel. And if all this was a formula, then it was one that worked well for Obolensky, keeping our hero gainfully employed for decades.

“Serge Obolensky abhors a vacuum,” teased one nightclub reviewer in 1959, as he’d transformed a hotel basement into “another of his imperial fashion bazaars. Colonel Obolensky has an eye for grandeur, réclame, décor and White Russian nights of gala. So he can be forgiven for not having an ear for dance music.” Harsh, perhaps, as Obolensky loved to dance, although maybe a man introduced to nightlife in pre-Revolutionary St. Petersburg might struggle slightly with the advent of rock’n’roll.

In other ways, however, he was a modernizer, and as such the recipient of criticism from the kind of hotel guest who never likes change. The New Yorker magazine once ran a piece, a classic of its kind, interviewing a woman called Clara Bell Walsh who’d occupied the same hotel suite for 43 years. “They don’t have this sort of thing today,” she’d told the reporter, pointing to the original furnishings she’d retained in her room. “The Russians have kind of colored this place up too much to suit me,” she complained. “What, the Communists?” the bemused journalist asked her. “Serge Obolensky!” came her furious reply.

Only war seems to have got in the way of Obolensky’s extraordinary career as a hotelier – and even then, The St. Regis Hotel helped shape this, our hero’s next great adventure. Obolensky, who’d taken American citizenship (and dropped the use of his title) in 1931, was keen to fight for his adopted country. Too old to enlist in the regular army, he joined the State Guard. But the Guard seemed unlikely to see action in Europe, so he asked a friend in the military how he could transfer to the commandos. “That’s easy,” came the reply. “Why don’t you talk to Bill Donovan? He’s staying in your hotel.” Obolensky spoke to “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services, who promptly took him on. And so after commando training which he said “nearly killed” him, Obolensky, by now 53, parachuted into occupied Europe, twice. In both cases, his mix of charm and courage won the day. In the first drop, he landed in Sardinia with just three other men and a letter from General Eisenhower to negotiate the surrender of the Italian forces on the island. Next, he jumped into France to prevent the retreating Germans from blowing up the power station serving Paris. He won over both the Resistance and the commander of the Vichy French. Then the main column of Germans finally surrendered to one Colonel Grell, “our plans officer, who had been my assistant manager at The St. Regis”.

In the 1960s Obolensky returned to the hotel where his career had begun, and in his memoirs discerned common ground between hotel-keeping and soldiering. “Hotels are a human enterprise,” he wrote. “You have to be known and liked by its rank and file, the waiters, the captains, the clerks, the manager – it all adds up to esprit de corps. Despite a good building and a good location, everything depends upon people – on goodwill, good service, and, in a sense, on personal friendships.” In a sense, human relationships lay at the root of the life Obolensky forged for himself in America. As that New York Times profile put it, “though cynics might attribute his success to the drawing power of his title, that would be to underestimate the magnetism of his personality and talent for friendship.” So did he ever feel slightly weary of another night of gala, of “Prince Serge Obolensky hosts”, of singing for his supper? If he did, he never showed it. “I just think that it would be the greatest mistake for an old bastard like me to quit,” he quipped when asked about retirement. At 80 he still did yoga every morning and went out most evenings, “leaving at midnight, without fail”, Ivan Obolensky recalls. “That was his rule.” Around this time, though, he gave up performing the celebrated Russian Dagger Dance. A highlight of New Year’s Eve balls for decades (with proceeds going to the victims of Communism), this involved Obolensky balancing on a rickety table while hurling flaming daggers at targets with a remarkable degree of accuracy.

He also abandoned his bachelor existence to marry for the third and final time to a woman four decades his junior, Marilyn Fraser Wall, from the wealthy suburb of Grosse Pointe, Michigan. And so it was there in 1978 that, some 88 years after it had begun at an Obolensky villa beside the Summer Palace of the Romanovs, this remarkable life drew to a close. Princely proof that life can be stranger than fiction.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Images courtesy of the estate of Ivan Obolensky, Superstock, Illustrated London News Ltd, Mary Evans, Bettman/Corbis, Conde Nast Archives, Corbis, Getty Images, Wire Image, Bert Morgan Arhive/Alamy, Popperfoto/Getty Images