Tell me a bit about your English childhood.

I was brought up in Richmond, just outside London, and went to boarding school in Wiltshire. We had a country house we went to at weekends. I used to ride ponies and go to gymkhanas, though I was never very successful. Then I studied at the Wimbledon School of Art and we [she and co-designer Keren Craig] launched Marchesa there. I never imagined I’d end up in America.

So how did it happen?

It was a gradual move. Nieman Marcus became our biggest client, and we were selling really well to Americans so we decided to set up an office in New York. When we first arrived, we were lent some studio space in the garment district in Midtown, but we couldn’t start working until 7pm when everyone else had left, and we had to do all our dyeing in the men’s bathroom. It wasn’t the most glamorous start for an eveningwear company. Eventually we got our own offices in the Meatpacking District, but we didn’t go out much because we were working so hard. Meeting my husband [the film producer Harvey Weinstein] sealed the deal, of course. Now my family is here, and my daughter India is about to start school.

Where are your favourite New York hangouts?

I’ve always lived in the West Village, which reminds me a bit of London.

Having children has given me a new perspective on the city: we’ve got a playground right on our street, which is very lucky. I like to walk to my offices in Chelsea along the High Line, a former elevated railway that’s been turned into a park. It has amazing views of the city and is beautifully planted, with cafés all along it. Both India and Dash [her second child with Weinstein, Dashiell] come into work with me a lot. My favourite shop in New York is Bergdorf’s; it’s beautiful, and I love the layout. And I love Showplace Antique + Design Center (nyshowplace.com), which is an indoor antiques emporium of old Louis Vuitton luggage and vintage clothing. I often go there and sift through everything for little treasures, looking for inspiration.

What are the hotels you love in New York?

I go to The St. Regis quite often for tea, and for fittings with very glamorous people who are staying there. The atmosphere is lovely because the service is fantastic yet it’s relaxed, which is a rare combination. I also love eating at the Waverly Inn, and if Harvey and I are going out, we like Per Se in the Time Warner building and the Monkey Bar uptown. But Harvey works so hard that if we do spend time together, it’s usually in Connecticut.

So how do you spend your weekends?

Our home in Westport is where I can really relax. When I was looking for somewhere for us to get married, I looked everywhere and eventually I said, “Why don’t we just do it here?” That’s not to say it all went smoothly. I made my own dress and the embroidered panels I’d ordered from India arrived stained brown, which was a bit of a heart-attack moment. And then I got the flu, so I was lying in bed pinning the dress together. But it all got done in the end. On a normal weekend, because we’re both so busy, we like to eat in and watch movies in our screening room. There is a restaurant in Westport that we love, the Dressing Room. It was started by Paul Newman, and it serves home-grown, organic food. Everything there is so fresh and delicious.

What other parts of the States are special to you?

I had my bachelorette party at Price Canyon Ranch, a really small place in Tucson, Arizona. I took my girlfriends, and we all shared rooms and went out day and night on horseback wearing pink cowboy hats and, I seem to remember, pink leotards. It was really fun and definitely anti-style. And I sometimes go with Harvey to Sundance. It’s a serious film festival, but because it’s in a ski resort lots of people bring their kids, and there’s a lovely relaxed atmosphere. So I go skiing during the day while Harvey works, and in the evening we all meet up.

What do you love about LA?

My favourite thing is the change of climate when you arrive. I’m always so happy to escape from New York in the winter. I head for The Way We Wore, which sells beautiful vintage clothes. I found a pair of matador trousers in there which inspired my last collection. I like to eat out at Cecconi’s and Soho House, which has fabulous views, but my favourite restaurant of all is Giorgio Baldi in Santa Monica. I always have the sweetcorn ravioli with truffles. It’s making me feel hungry just talking about it.

What’s it like dressing people for the red carpet?

Really nerve-racking. You feel an incredible responsibility. They’re walking out in front of the cameras and about to be critiqued by the world, so you want them to feel their best. Your heart’s in your mouth, thinking – don’t let anything happen to the dress! Harvey and I are often at the same event, both feeling nervous. Still, we’re very lucky that our industries overlap so much that we need to be in the same place.

How do your worlds converge professionally in other ways?

Harvey is incredibly supportive of what I do, and I love what he does. In fact, I’ve just directed a short film for Canon’s Project Imaginat10n film festival, and I’ve been using every bit of help from him that I can get. I’ve told him if he ever feels like designing a dress, I’ll be there for him.

Has the rise of red-carpet dressing influenced the way ordinary women dress?

I think so. When we first started Marchesa, people told us nobody did evening dress any more. These days, people don’t reject it as old-fashioned. It would be very boring if there wasn’t a spectrum of things to wear, and we only had cocktail dresses. Wearing an evening dress is fun; you feel gorgeous, and it’s romantic. There’s nothing more magical than walking into a room where everyone looks incredible.

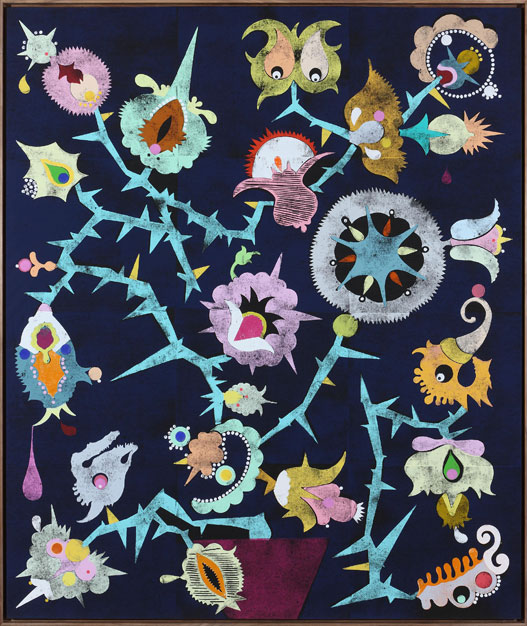

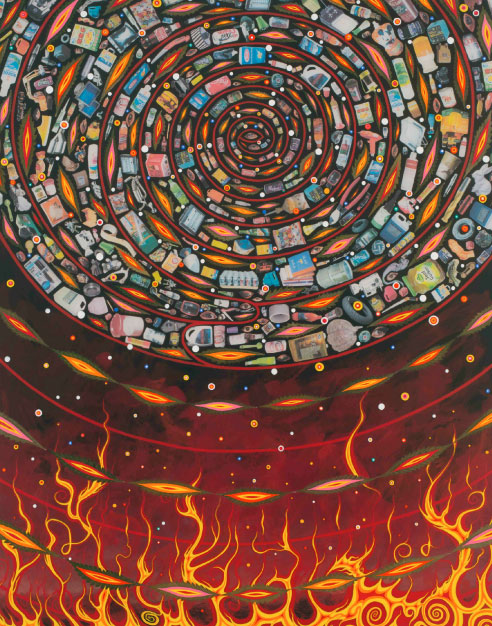

Where do you get your inspiration for Marchesa?

From movies, from museums, at night on the internet looking at artists…sometimes I’m zoning out on the treadmill when I have an idea. Our new contemporary line, Marchesa Voyage, came about when Keren and I were on vacation, and we realised it would be great to design some clothes we could take with us that had the Marchesa attitude and the prints, but not the corsets and heavy beading. I’m really excited by it.

Do you design differently for American and British women?

I don’t like to generalize. I’m not designing for a particular British or American woman. You might find you have more success with hotter colour palettes in warmer parts of the world, but the same would apply in the States. My own look hasn’t really changed since moving here. It’s hard to be groomed if you’re working with your hands, and I’ve never been a weekly mani/pedi girl at all. I just can’t sit still for an hour. That’s why I love the new stick-on nail art we’ve brought out with Revlon. The nails are designed to match our embroidery, and they take about two seconds to put on.

What would you miss if you had to leave the States?

The service and the can-do attitude. New York is a 24-hour city, and I do find it frustrating when I leave it. What do you mean I can’t get what I want at 2am?

What advice would you have for visitors to America?

Explore as much of it as possible, because it’s such a diverse place. Beaches, skiing, beautiful landscapes and city life. It’s all here.

Images by M.Sharkey/Contour by Getty Images, Camera Press