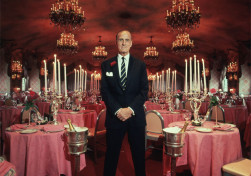

It’s no small task, accomplishing the makeover of an iconic hotel – and the renovation of The St. Regis Rome has taken multiple teams more than two years to complete, at a cost of €48 million (approximately $56 million). All this, as general manager Giuseppe De Martino puts it, to equip the hotel for “a new generation of luxury travelers to the Eternal City”. De Martino was the man with the daunting task of managing this Roman epic of a “refurb” job, while the creative lead came from the celebrated interior designer, Pierre-Yves Rochon. And as both men would readily concede, it is both a privilege and an added source of pressure when the property getting this, the most loving of face-lifts, is a quintessential European grand hotel of the Belle Époque, opened as “Le Grand” in 1894 by none other than César Ritz, the leading hotelier of his time.

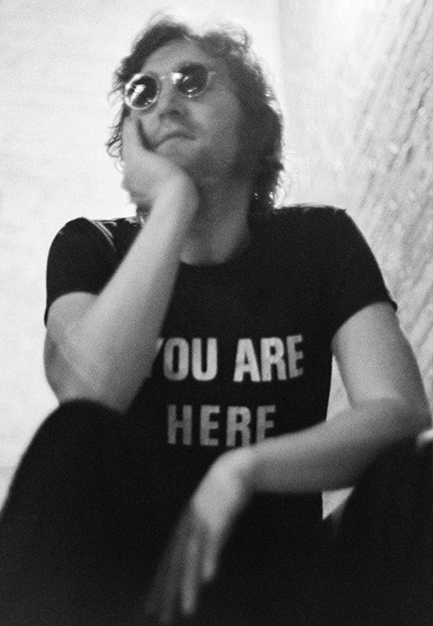

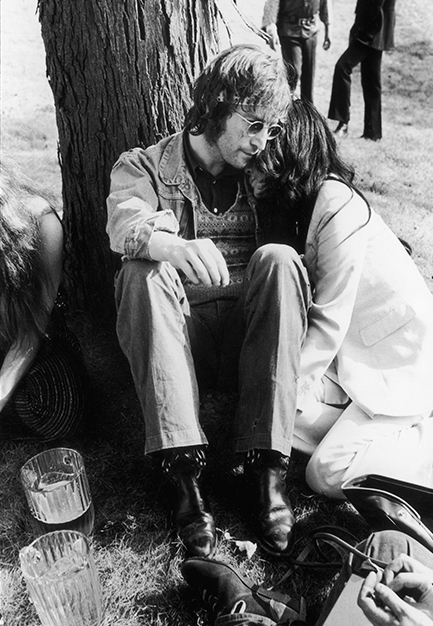

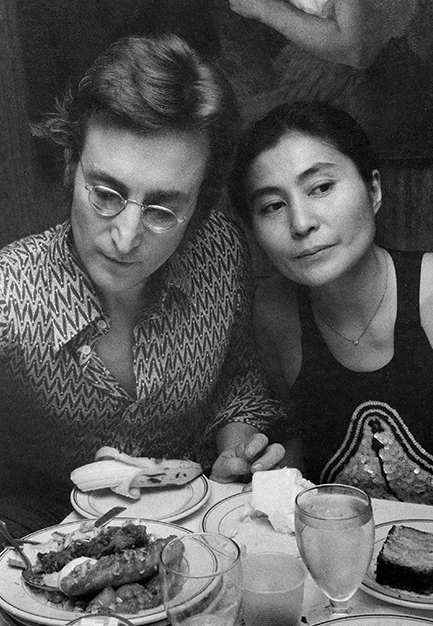

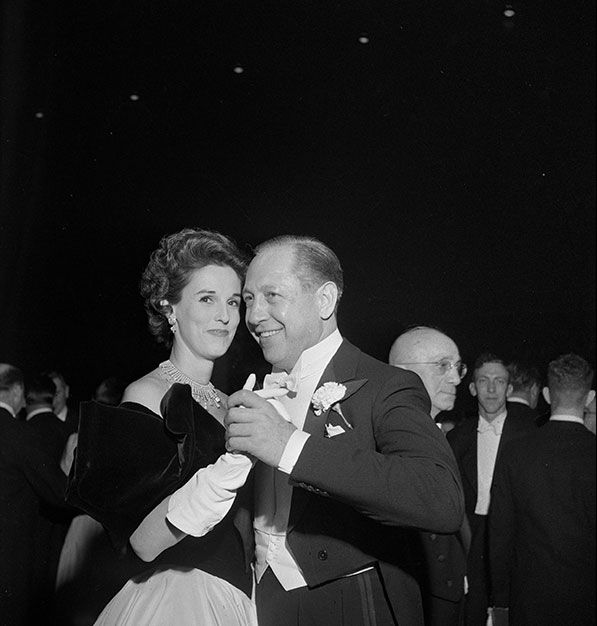

A great metropolitan hotel isn’t just a place for visitors to stay in, it must also be part of the surging life of the city. And, true enough, Ritz’s hotel was the stage for some extraordinary moments in the modern story of Rome – beginning with its gala opening, which was attended by the Pope, the German Kaiser and the King of Italy. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the Italian royal family used the hotel as a kind of convenient and more modern extension of the nearby Quirinal Palace, hosting court occasions in its public rooms. Alfonso XIII of Spain spent his gilded exile in one of its luxurious suites, while the parents of his eventual successor, King Juan Carlos, met at a reception celebrating a family wedding held here. For a time, Mussolini had an office in the hotel, which, within days of Rome’s Liberation in June 1944, hosted the first meeting between Italy’s provisional government and the triumphant Resistance. Gianni Agnelli – Fiat boss, arbiter of style and architect of the Italian post-war boom – kept a permanent suite here for many years, and poached the head doorman when he finally bought a home in the city. And it was here that Liz Taylor, Richard Burton and other Hollywood stars stayed and partied and tapped into Rome’s glamorous La Dolce Vita era while filming at the Cinecittà film studio.

As you’d expect, given the hotel’s unique provenance and storied past, this Roman renovation was conducted under the watchful gaze of various eagled-eyed guardians. First there was the Accademia di Belle Arti – Rome’s fine art academy – which was involved throughout the whole process, but most especially with the restoration of the fine frescoes adorning the vaulted ceiling of the ballroom. And, as is always the case with a hotel makeover, there are also the opinions of regulars to consider: the guests who stay whenever they visit Rome, and the Romans who have been wining, dining and marking important family occasions here for years, perhaps across several generations, all of whom have a deep affection for this much-loved building.

“This hotel has an extraordinary, evolving legacy,” says De Martino, deftly signaling the need to embrace the future while respecting the property’s heritage, for every generation has its own notions of what constitutes luxury. When we’re staying at a grand hotel from this era, we might expect high-tech facilities – but surely not at the expense of grandeur, elegance and a slightly old-school decorum? It is telling that more than a century after César Ritz’s death, we still use the word “ritzy” to describe an environment that is plush and fancy and serviced to the hilt. Yet Ritz was just one of several brilliant innovators of this era who transformed the way the wealthy traveled, and who collectively established many of the luxury codes that we still follow today – and whose innovations provided the context for Ritz’s Le Grand Hotel.

Some of these luxury innovators were Europeans. Ritz himself was Swiss, rising through Paris’s restaurant scene to emerge by the 1890s as Europe’s most celebrated, sought-after hotelier. Indeed, his new hotel in Rome was in direct response to a request from Italy’s prime minister, who buttonholed Ritz in the lobby of a London hotel to ask him to build a hotel worthy of Rome’s still relatively new status as the capital of unified Italy. Ritz’s culinary partner in Rome was French – the master chef Auguste Escoffier, who modernized French haute cuisine and codified fine-dining as we still know it, with distinct courses, à la carte menus and “brigade service” in the kitchens.

But another popular space in Ritz’s new hotel was the American bar – a nod not just to the freshly imported cocktail culture, but also to the fact that much of the drive for the new luxury came from the US. For the wealthy scions of America’s Gilded Age were crossing the Atlantic in ever greater numbers – in search of pleasure, art, or a titled European for their heiress daughters – and these latter-day Grand Tourists were also traveling in ever greater comfort and style. Ocean liners were becoming faster and more elegant, as were the trains pulling into Rome’s Termini station, just a conveniently short carriage-ride or stroll from Ritz’s new hotel. And the entrepreneur who had transformed train travel was an American: George Pullman. Pullman invented the vestibule train – that is, one where the carriages are interconnected – and with it, the sleeper car and the dining car, while at this time the private train carriage was a must-have for kings and emperors, maharajas and plutocrats alike. Superbly appointed and way beyond the means of most train travelers, these “Pullmans” were the Belle Époque equivalent of the private jet.

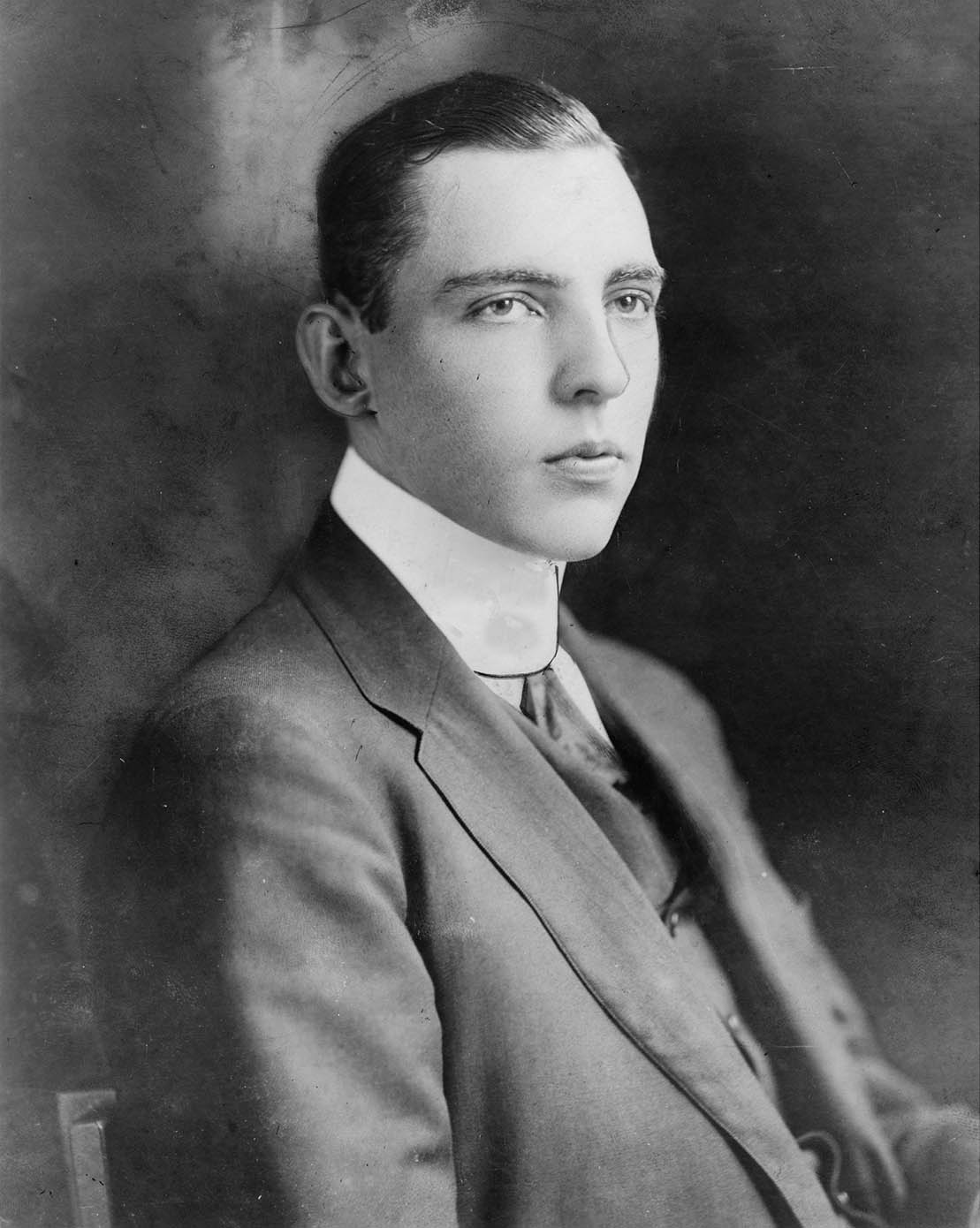

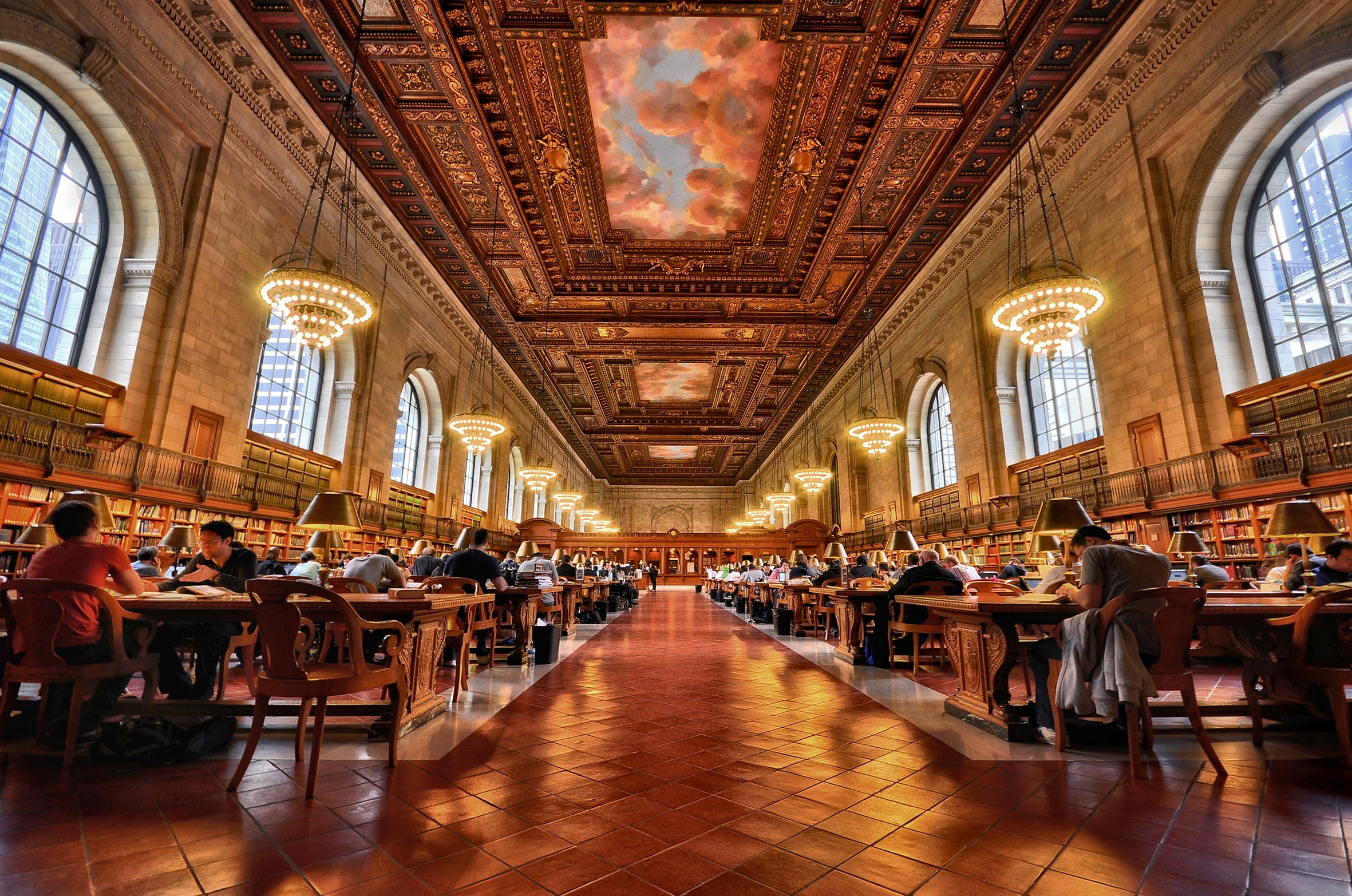

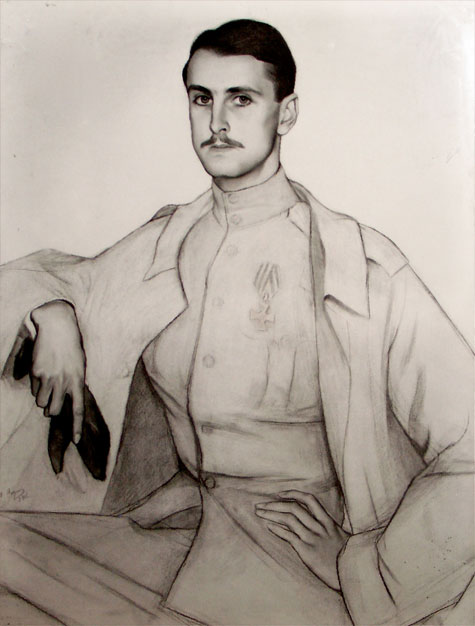

And then of course there were the Astors, the American dynasty who for more than a century led New York high society – and led hotel-keeping in the city, with a series of hotels that introduced generations of New Yorkers and visitors to now-standard innovations such as the in-room phone, the en-suite bathroom, or that singular blessing on a humid summer’s day in Manhattan, air-conditioning. The ultimate expression of Astor opulence and savoir faire would be The St. Regis New York, opened by John Jacob “Jack” Astor IV in 1905, within a decade of Ritz’s Grand Hotel in Rome. True, the footprints of the hotels are different: Rome was modeled on a Roman palazzo, while Jack Astor’s palace on 5th Avenue was an early skyscraper, dwarfing the townhouses of “Millionaire’s Row” beside it. But they visibly share what we would now call “luxury DNA” – and all the signature qualities of the grand hotel, combining a great address with splendid interiors and superb service, which Ritz famously defined. “See all without looking,” he urged his staff. “Hear all without listening; be attentive without being servile; anticipate without being presumptuous.”

As a gifted amateur inventor and the author of a bizarre but oddly prescient science fiction novel which predicted, among other things, the era of mass air travel, Jack Astor would certainly have understood the need to update a hotel, as would César Ritz. Pierre-Yves Rochon and his team began the process by spending time in the Roman property – and looking at the blueprints, which is surely the interior designer’s equivalent of fashion’s “mining the archive”. And in two of the largest public spaces – the ballroom and the grand foyer – Rochon’s aim has been to return the building to something much closer to the hotel that Ritz and his architect Giulio Podesti created.

In the ballroom, the restorer Patrizia Cevoli and her team set about cleaning the frescoes commissioned by Ritz from the Roman artist Mario Spinetti – and removing the work of previous, less authentic restorations. The process took Cevoli and her team of 12 specialists some six months of “intense and painstaking” work. “I develop a special bond with an artwork when I’m restoring it,” explains Cevoli. “Once it is finished it is a very emotional moment, seeing the original work of art come back to life.” And today Spinetti’s mythological scenes once again possess the vivid hues in which he painted them more than a century ago.

Color had a major role to play in Pierre-Yves Rochon’s re-imagining of the other public rooms, in which he used what the designer describes as an “aristocratic Roman palette” of white, dove gray, yellow and powder blue, “enriched with noble shimmers of gold and silver”. The aim, he explains, was to celebrate the light of Rome in all of its forms. The effect of this is especially striking in the grand foyer, which Rochon returned to its original concept as a kind of winter garden, once again on a single level as Podesti had designed – in the process rediscovering an airy, piazza-like space which truly bursts with light from the glass cupola above.

Also put into play was the keen eye of Parisian gallerist Françoise Durst, who sourced works of art that adorn the public spaces and the 100-plus rooms and suites that have been renovated. Meanwhile, Rochon’s team oversaw a kind of aesthetic audit of the hotel’s collection of furniture – in Louis XV, empire and art deco styles – to assess what needed to be restored, replaced or else redeployed. These included some exceptional pieces from a previous refurbishment in the 1960s by the celebrated Maison Jansen studio, which also worked on Jackie Kennedy’s redecoration of the White House. And the team commissioned some spectacular new decorative highlights to add a contemporary feel, such as the blue Murano glass chandelier in grand foyer. It’s one of Rochon’s many contemporary touches that chimes elegantly with the hotel’s fine proportions and those traditional Roman materials of travertine, mosaic and Italian marble. For this is, after all, a grand hotel in the Eternal City.

Your address: The St. Regis Rome; The St. Regis New York

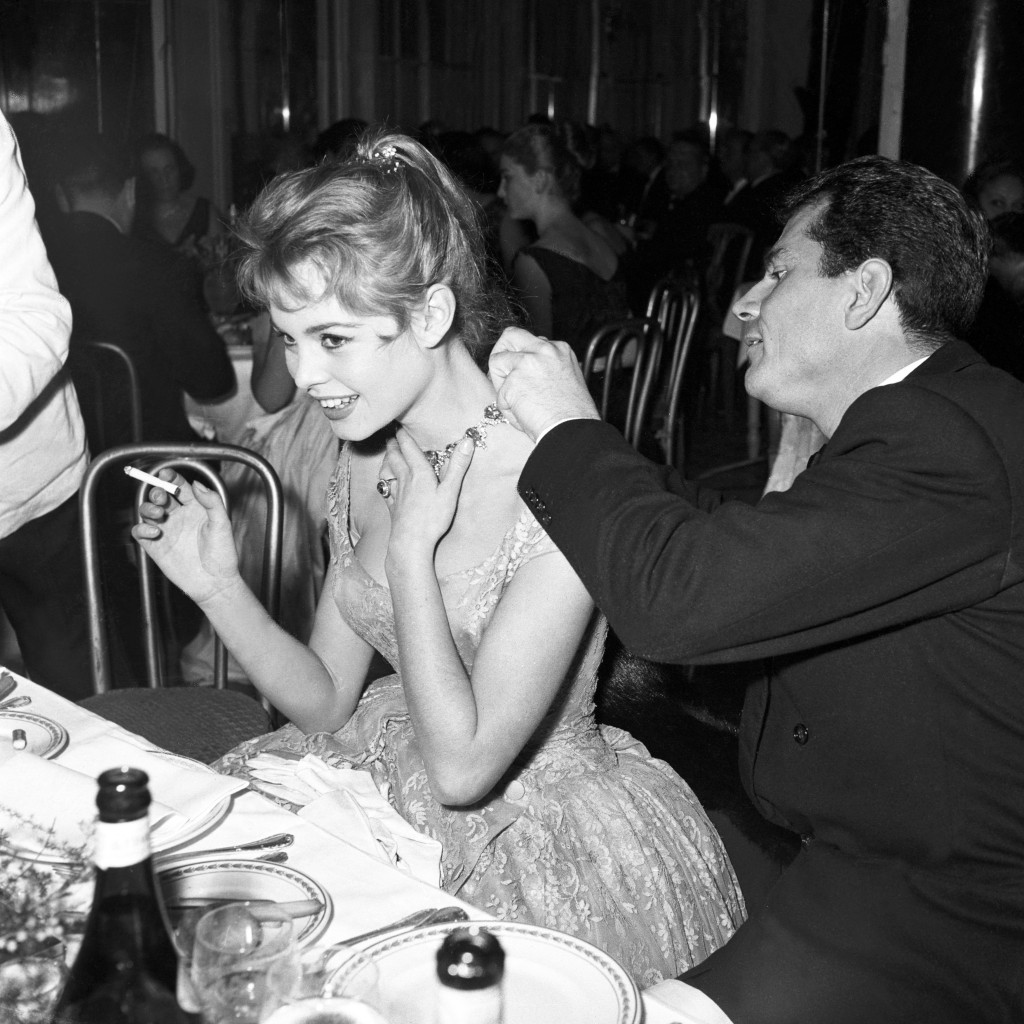

A 1930 gala evening

(© Archivio Luce)

A postcard from the Grand Hotel

(© Historic Hotels Photo Archive)

Kirk Douglas and Elizabeth Taylor, 1961

(© Getty Images)

Vittorio de Sica and Sofia Loren at the Grand Hotel in 1955

(© Bridgeman Images)

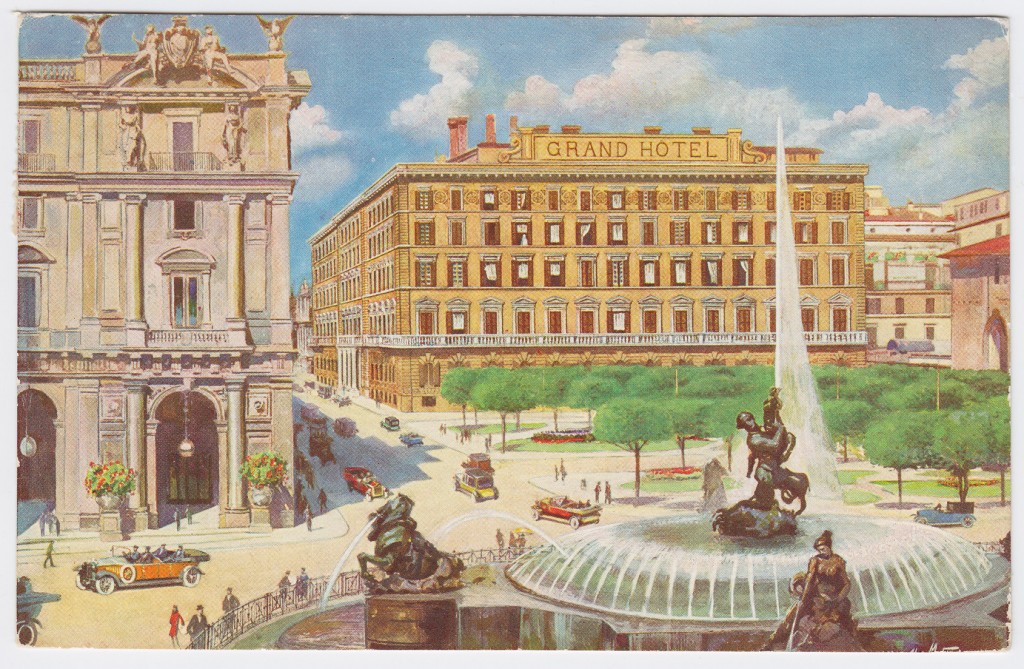

A postcard from the Grand Hotel showing Rome’s Piazza della Repubblica

(© Historic Hotels Photo Archive)

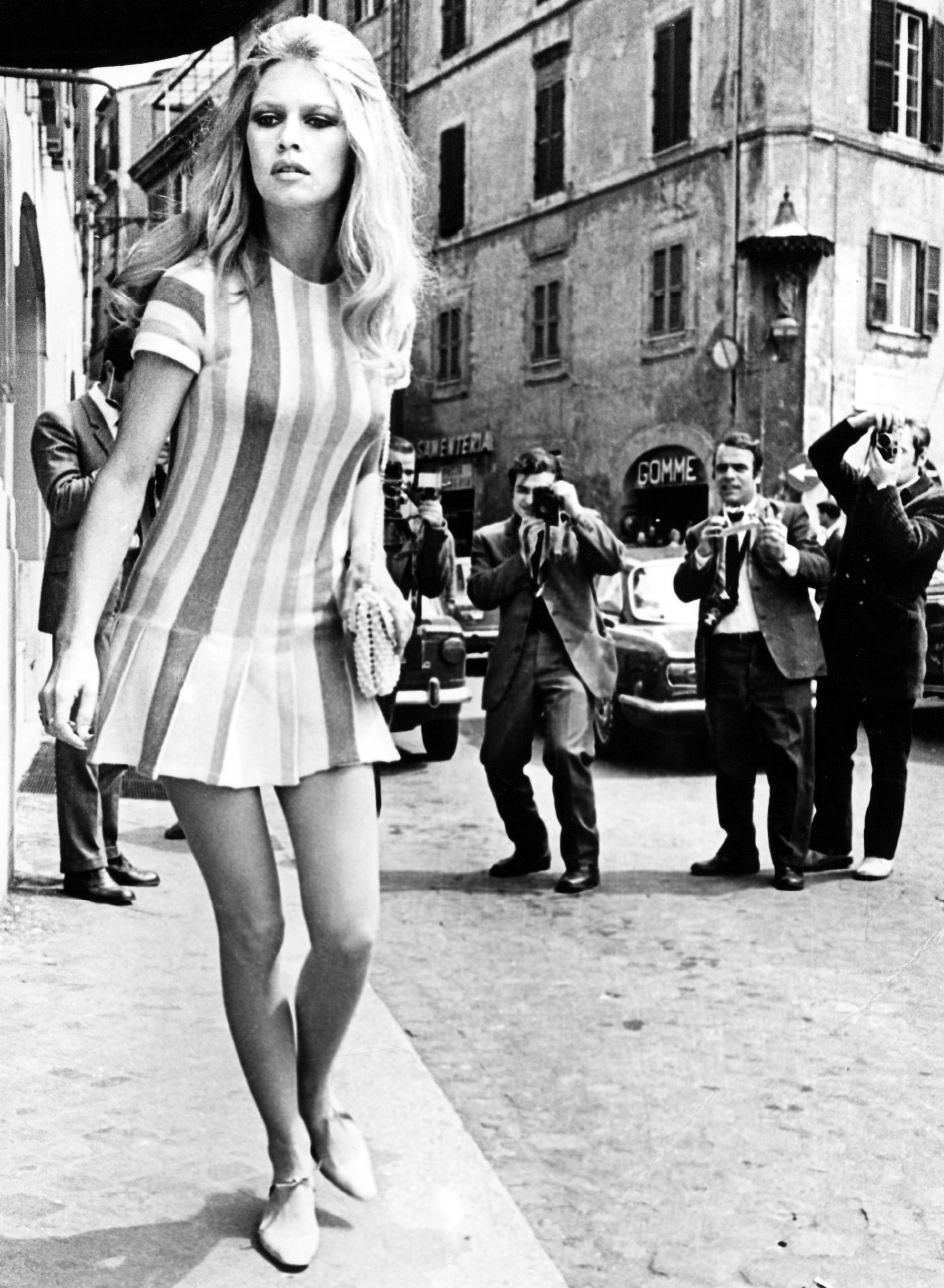

Brigitte Bardot attends a cinema awards ceremony in 1956

(© Historic Hotels Photo Archive)