A couple of years ago, a Bolivian chef told me he wanted to reclaim the chili for his country. The argument, that hot peppers were first cultivated in the Andean high plains and spread north from there, is supported by food archaeologists.

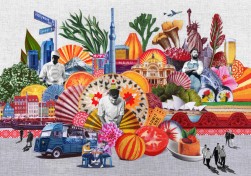

If the message could only get out, it might actually do Mexico a favor. Because the concept many people have – that Mexican food is mainly about heat – is totally outdated. “Mexico has the most misunderstood cuisine in the world,” says Edgar Núñez, chef and co-owner of Mexico City’s Sud 777, a regular fixture on the annual S. Pellegrino Top 50 Latin American Restaurants list. “It’s extremely complicated and sophisticated, with avocado, vanilla and chocolate, and dozens of other flavors at least as important as hot spices, which we may or may not provide as a side dish at the end. Mexican chefs rely on a lot of produce only available here, which is one of the reasons why great Mexican cuisine is not always available globally. We have more than 60 distinct cultures in the country – many with their own language – and all influence our cuisine.”

The menu at Sud 777, in the upscale El Pedregal district, entices with dishes like smoked watermelon, guajolote (turkey) with mole negro and beef tongue with local beans. “When I cook, I’m aware of deep connections with the soil, our farming traditions and my own memory. But our clients are well-traveled foodies, and they’re increasingly looking for more than traditional food.”

The epicenter of culinary experimentation is Mexico City – the nation’s inland food hub. At Quintonil in the leafy Polanco embassy district, Jorge Vallejo crafts edgy – and extraordinarily beautiful – concoctions from cactus, heritage corn and escamoles (ant larvae, also known as “Mexican caviar”). At Enrique Olvera’s Pujol, the tasting menu includes wonders such as octopus with habanero ink, salt made from toasted maguey worms and a juiced white corn that goes by the evocative Náhuatl name of “cacahuazintle”.

In some respects, “mole” – which simply means “sauce” – is the essence of Mexican cooking. Olvera’s “Mole Madre” – Mother Mole – evolved from the standard seven-day process of reheating fruit, nuts, bitter chocolate, tomato and peppers and other ingredients in a comal, a heavy cast-iron griddle – into an ongoing experiment. “We continued heating it indefinitely,” he says. “We found that the mole never stopped evolving.” At the new Pujol, which opened last year – modeled on Olvera’s New York restaurant Cosme – you can try moles slowly heated for well in excess of 1,000 days. “Mole is a universe in itself, so we present it only with tortillas,” says Olvera. In this he’s emulating the Mexican capital’s superb street-food vendors; when a busy office worker needs a fast fix of good food, simplicity and flavor rule over image or presentation.

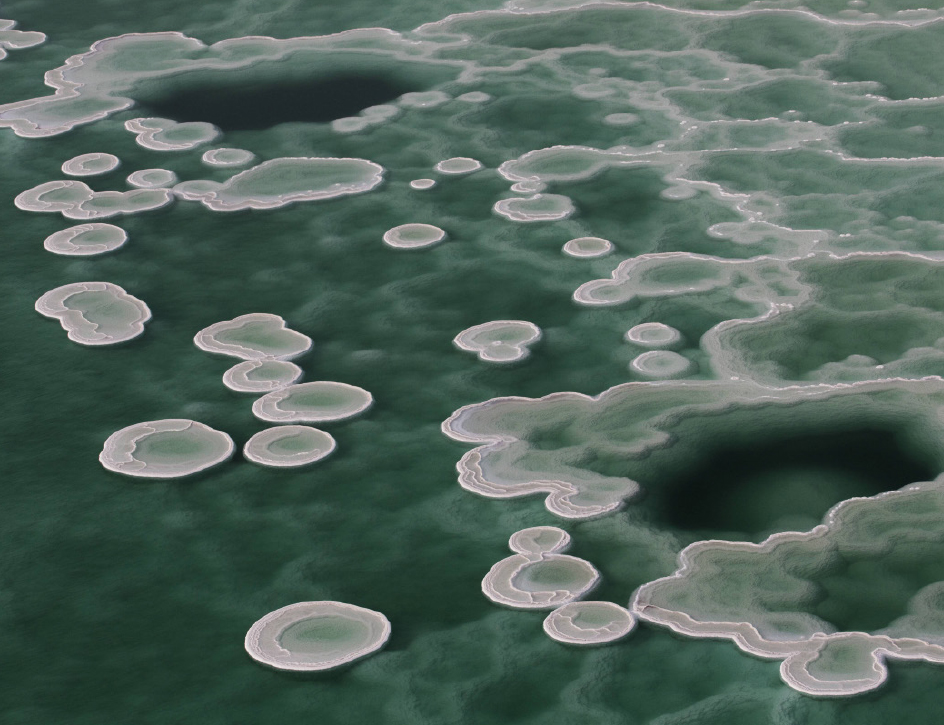

Mexico is larger than Indonesia, more topographically diverse than Canada – and it has an odd shape. To go overland from Cabo San Lucas in Baja California to Cancun, without catching a ferry, would involve driving 3,730 miles. It’s unsurprising then, that regionality remains a powerful force. Oaxaca does its own type of mozzarella. The chile poblano – a mild green pepper used in chiles en nogada, the de facto national dish – takes its name from Puebla. Tequila was a place before it was a drink. From Yucatán comes the pit-oven technique known in Mayan as p’ib – and responsible for the al fresco fiesta classic that is cochinita pibil (slow-roasted pig seasoned with annatto seeds).

To simplify things, chefs and guide-writers, have grouped produce and techniques into seven main regions. But for visitors, every state, every city, every beach-stop, signifies an opportunity to savor something different. That said, Mexicans of the past – Aztecs, Mayans, Toltecs or Spanish Conquistadors – were tireless travelers, and it’s notable that you can usually obtain fish dishes even when deep inland, eat steak in the desert, and, along the Pacific coast at, say, Punta Mita, enjoy suckling pig as well as ceviche. Beyond Mexico, several globalizing trends are afoot, from the ubiquitous burrito bar to the ever-replicating chains with vaguely Latino names and logos featuring cacti, sombreros and lizards. But, thanks to chefs such as the aforementioned Mexico City superstars, Val Cantu in San Francisco and Copenhagen-based Rosio Sánchez, a meal of “Modern Mexican” has become a highly desirable night out in all the world’s coolest cities.

You cannot, of course, have great cuisine without a proper drink. Baja’s wines have long been held in high esteem, not least in the “other” California north of the border, which seems to import more bottles of Valle de Guadalupe vintages than does the rest of Mexico. But the real revolution right now is taking place in the realm of stronger, more spirited beverages.

Tequila and mezcal are distillates made with agaves; the key difference is that tequila is made exclusively from the agave tequilana (blue agave), and can only be produced in the state of Jalisco and in small areas of four other states. Some 30 agaves can be used to make a mezcal. Once a farmers’ drink, new artisanal varieties of mezcal have started to appear on bar menus around the world. Smoky notes, deep bodies and complex aftertastes characterize the experience of slowly sipping a premium mezcal – with neither a worm nor a long mustache in sight.

Your address: The St. Regis Mexico City; The St. Regis Punta Mita Resort