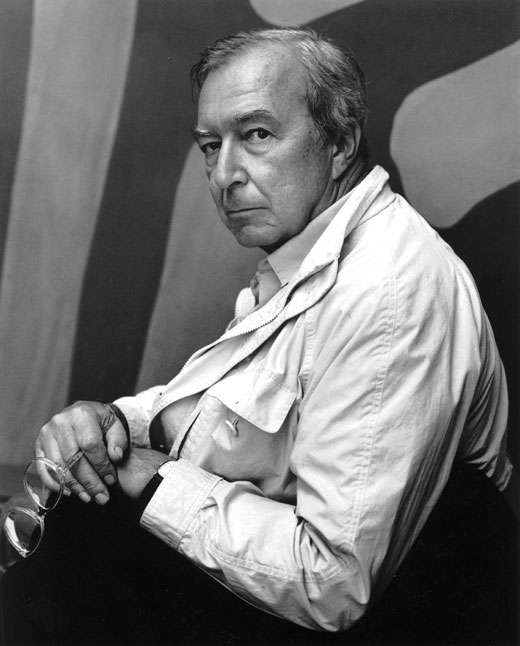

Now 83, Jasper Johns has long been ranked among the major, ground-breaking figures in American art. He was only 25 when his images of the Stars and Stripes broke free from the prevailing supremacy of Jackson Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists. In the mid-1950s Johns was hailed as a controversial young rebel, following the example of Duchamp rather than the American titans, Pollock and Rothko. After moving to New York from South Carolina in 1949, Johns felt ready to subvert the Abstract Expressionist approach. He anticipated the emergence of Pop Art in the 1960s, and his inventive outlook opened up all kinds of possibilities for art in the second half of the 20th century.

Johns thrived on collaboration. Far from isolating himself as the lone genius in his studio, he worked with fellow artist Robert Rauschenberg, the experimental choreographer Merce Cunningham and the avant-garde composer John Cage. They became his friends, and Johns extended his creativity with these adventurous projects in dance and performance. Johns began making prints in 1960 after accepting an invitation from Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) to make radical works on paper. This innovative print studio, based in a cottage on Long Island, was founded by Russian émigré Tatyana Grosman and her husband Maurice. Johns relished working with them, and continues to experiment with ULAE. Its current leader, Bill Goldston, says, “Jasper is still very involved in doing prints. He loves the activity. A lot of people in art today don’t know how to make things. But prints offer Jasper the chance to become process-involved, and to develop a language from exploring his working method. He’s always experimenting, like a scientist in the lab. Printmaking is tailor-made for Jasper.”

Now a special exhibition, at the Whitechapel Gallery in Windsor, Florida, explores the presence of the body in Johns’ prints. Whether ghostly or silhouetted, these ever-changing faces and figures play a fascinating variety of roles in his images. Johns is an artist perpetually committed to renewal. When I interviewed him some years ago, he told me that success had made him “more willing to take chances, to question the possibilities of my thought and what might or might not be considered interesting”. Looking back on his career, he said, “throws finished work into the past tense more quickly, and provides me with a trigger for the new”. That is why Johns’ overall achievement has been so remarkable, filled with surprises and perceptive delight.

Photograph: Getty

Your address: The St. Regis Bal Harbour Resort

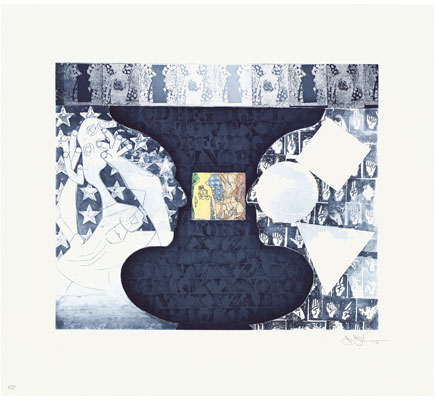

Shrinky Dink 3, 2011

In this print the dark vessel occupying the center of the space seems to dominate everything around it. But then we begin to notice the other elements that Johns has introduced. On the left, a pale head in profile stares across at the other side of the image, and stars from the American flag dance over the face as if in jubilation. On the right, however, geometric forms float in space: a square, a circle and a triangle. The face seems to be contemplating these shapes, and Goldston remarks that its features “look like Jasper himself in profile”. But taken as a whole, this print is far more than a self-portrait. Across the top, a row of small figures introduces the suggestion of a crowd. Maybe they are an audience gazing, like us, at the tantalizing, dream-like strangeness of the world that Johns has conjured up.

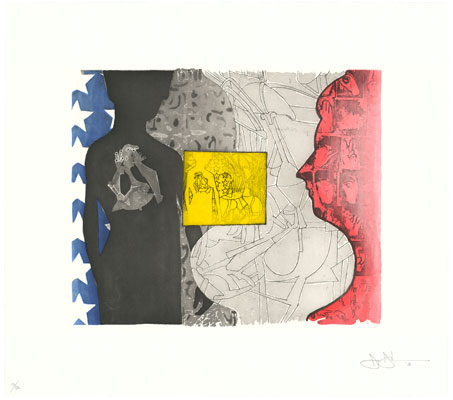

Untitled, 2010

A red face appears in profile on the right of this seductive design, and its contour also defines the side of a pale vase. Johns allows yellow to sing out from the rectangle in the middle, and the entire image is among his most beguiling achievements as a printmaker. “This piece was done for the Museum of Modern Art, as a donation,” says Goldston. “They were able to sell the entire edition of 50 as a fundraiser.” Johns has benefited from the exceptionally rich collection at MoMA since he settled in New York aged 19. Now, in his late period as an artist, he still enjoys visiting and measuring himself against some of the finest masterpieces of modern art. But this print suggests that earlier civilizations also fire his imagination. The dark figure silhouetted on the left has the quality of an ancient statue.

Winter, 1986

The title of this etching seems straightforward enough, and shows how fascinated Johns became with the elemental theme of the four seasons. But the images in Winter emerge with slow, quiet subtlety from the prevailing darkness. On the right, we notice a ghostly snowman figure that appears to be spattered by snowflakes. “It looks a bit strange, and the snowman reminds me of Jasper himself,” says Goldston, who points out that the shadowy pots are by the early American potter, George E. Ohr, “and Jasper has a collection of Ohr’s work”. But there are also references to the suffering figures in the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald (c.1470-1528), whom Johns admires. This work, now in a museum in Alsace, has been an immense source of inspiration for Johns.

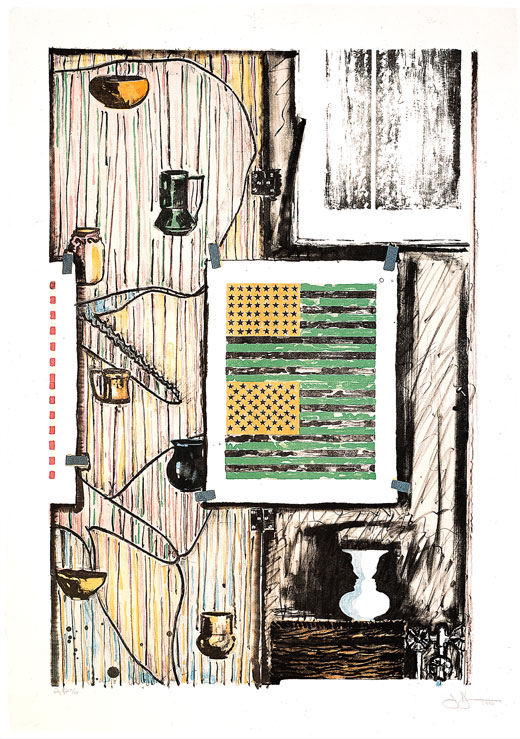

Ventriloquist, 1986

Although this print was made 30 years after Johns first became obsessed by the American flag, the Stars and Stripes assert themselves in the middle of a wall. Goldston explains that “the room could be based on Jasper’s bathroom. He used to live in a rustic farmhouse in Stony Point, New York, and you can see his water-closet on the right.” Marcel Duchamp, one of Johns’ artist heroes, created a notorious masterpiece in 1917 by purchasing a ready-made urinal and turning it into an artwork called Fountain. But Goldston thinks Ventriloquist was also inspired by the view from Johns’ own bath. It is easy to imagine moisture from the hot water streaming down the wall and making the glass fuzzy. This atmosphere is vividly conveyed and adds to the aura of mystery.

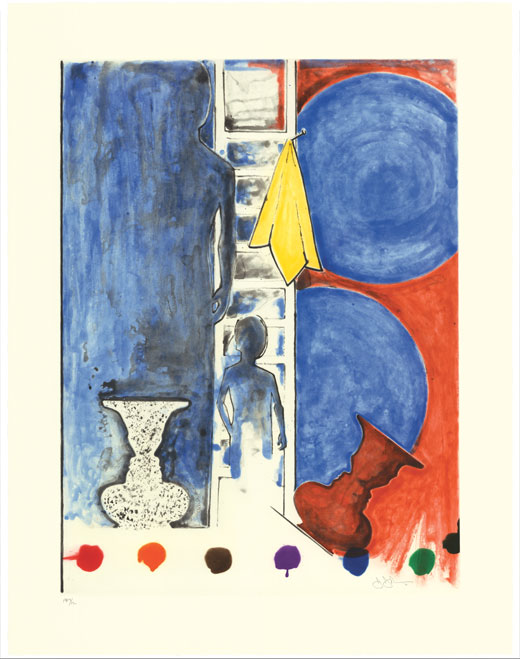

Untitled, 2011

The recurring motif of the vase is prominent in this tall, richly colored print, in which Johns rejoices in the sensuous orchestration of red, yellow and blue. “There are two figures,” says Bill Goldston of Universal Limited Art Editions, “one young and one old.” The latter is half-hidden in shadows on the left. Johns is at his most elusive and dream-like here, inviting us to puzzle over the identity of the blue circular forms on the right. Mortality seems present, and we may wonder if the vase contains the ashes of someone recently deceased. Johns leaves everything open to interpretation – even the print’s title offers no clues. Along the base, he leaves a row of colored spots. “He did all the etching himself,” says Goldston. “A man who can do this kind of technical work is in a class by himself.”