Throughout the 1950s and early '60s, Rome was the coolest city on earth, synonymous with fashion, style, design, glamour, a vibrant if sometimes disreputable nightlife – and, of course, movies. The epicenter of all this excitement and frenetic activity was a hitherto-unremarkable 200-yard street named Via Veneto. It was here that international high society would gather: the rich, louche and beautiful. There were movie stars and international financiers; haute couture tycoons and minor noblemen; millionaire playboys and stunning models, dressed to kill. The stories that emerged from this small street made it one of the most famous places on earth.

The after-dark activities, and sometimes outlandish behavior, in bars, restaurants and nightclubs on and around Via Veneto were the stuff of worldwide gossip. It looked like one long, wild party to which only the gilded and glittering were invited. All this lasted a decade or more, and from the outside, at least, it looked like a sweet life. No surprise, then, that the greatest film documenting the era was called La Dolce Vita – even if its title was sardonic.

What a scene it was. On any day in this feverish period it was hard not to catch sight of people so famous they could be identified by their surnames alone: Bardot. Sinatra. Ekberg. Welles. Lollobrigida. Mastroianni. Loren. You might glimpse Prince Rainier, Aristotle Onassis, the Aga Khan, Jackie Kennedy, King Farouk. Not to mention Burton and Taylor, or Liz and Dick, as the papers called them when they visited Rome to shoot the epic Cleopatra, and carried on an illicit affair that made global headlines for weeks on end.

While the film was being shot in 1962, the couple stayed at what was then called the Grand – which has been known as The St. Regis Rome since the turn of the century – and it became one the film’s informal production offices, with ordinary Romans waiting in line to be auditioned for lavish crowd scenes. The gorgeous belle époque palace, founded in 1894 by the legendary hotelier César Ritz, had become a Roman home away from home for dozens of stars, ranging from Kirk Douglas, Jack Lemmon, Burt Lancaster, Ava Gardner and her then husband Frank Sinatra (sometimes quarreling furiously) to Fiat’s playboy tycoon Gianni Agnelli, who maintained an apartment there all year round.

Jess Walter’s bestselling 2012 novel, Beautiful Ruins, gives a flavor of the place. One of his characters, an Italian man of modest means named Pasquale, enters the hotel to see hundreds of extras for Cleopatra being cast: “The mahogany door opened on to the most ornate lobby he’d ever seen: marble floors, floral frescoes on the ceilings, crystal chandeliers, stained-glass skylights depicting saints and birds and glum lions. It was hard to take it all in, and he had to force himself not to gape like a tourist...”

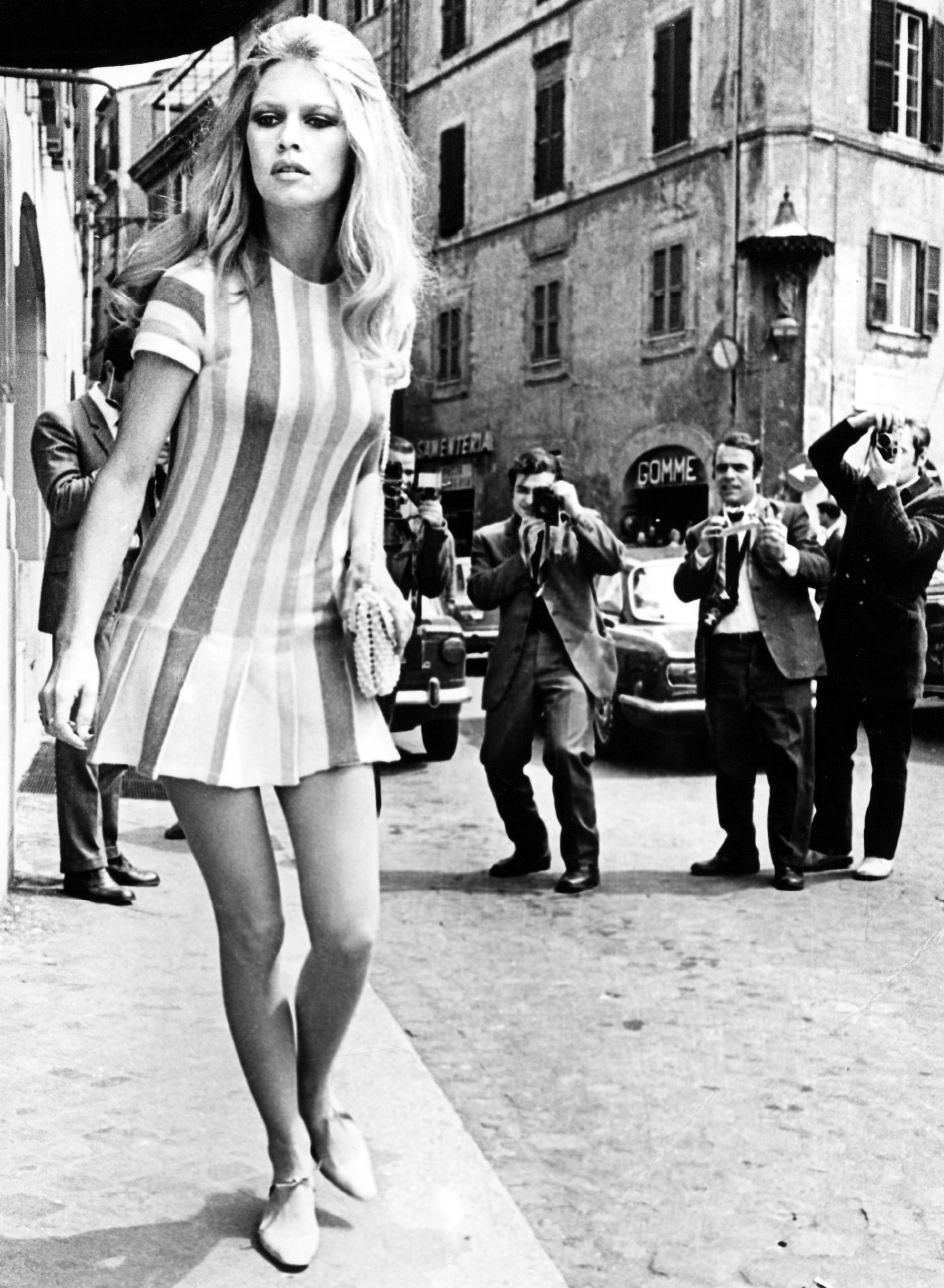

Via Veneto was heaven for the press, even in daylight, with all these famous people strolling and behaving impeccably. After all, they were rich, elegant, fashionably dressed by chic designers – and their images sold newspapers. Journalists and cameramen worked the Via Veneto beat in pairs, nosing out juicy titbits of gossip. Any celebrities behaving in an unseemly manner found their activities captured as they fled from gangs of ruthless cameramen, indifferent to their feelings and privacy. These men – some on Vespas, some simply sprinting – came to be known as paparazzi – after Paparazzo in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, the photographer sidekick to Marcello Mastroianni’s gossip columnist.

The paparazzi made the lives of some celebrities sheer hell. One of their favorite targets was Anita Ekberg, famous from La Dolce Vita as the sex-goddess actress who provocatively waded into the Fontana di Trevi and beckoned Mastroianni to join her. She and her husband, English actor Anthony Steel, were often out late on Via Veneto, sometimes openly arguing, with Steel frequently quite tipsy. He would literally fight back at the paparazzi, throwing punches. On one occasion Ekberg felt so persecuted by paparazzi who had tailed her all the way home, she grabbed a bow in her house and fired off arrows at her pursuers.

The standoffs between celebrities and paparazzi, out for scandalous photos that hinted at adultery or inebriation, became an almost nightly melodrama. Scuffles, shouting, chases and recriminations were commonplace. It wasn’t always seemly, yet the whole world seemed to be watching.

The phenomenon of La Dolce Vita seemed to emerge from out of nowhere, and several unlikely elements contributed to bring it into being. The most remarkable thing about it was the speed with which it happened and its time-frame: only a few years previously, the Eternal City was a devastated place, having been occupied by invaders – first the Nazis, then the Allies – with large sections of it reduced to ruins. Plus, of course, Italy had been on the losing side in World War II; it was a Fascist nation ruled mercilessly by the tyrannical dictator Benito Mussolini. Yet only five years after hostilities ceased, it felt as if the western world had swiftly forgiven Italy, and Rome re-assumed its place as a friendly international playground.

Three great neo-realist Italian films, all shot so cheaply and convincingly they looked like documentaries, helped to sway opinion, especially in America. Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) and Vittorio de Sica’s Shoeshine (1946) and Bicycle Thieves (1948) convinced the world that Rome’s citizens were mostly poor, decent and struggling to get by in their beautiful but war-ravaged city.

It also helped that Italy underwent an economic resurgence in the post-war years: “il boom”, as it became known. This was partly due to generous American aid under the Marshall Plan, but was also thanks to the country’s production of well-designed products for mass consumption: domestic appliances, Fiats and Vespa motor scooters, all of which introduced us to items that were both chic and iconic.

After the war, the population around Via Veneto changed. Although once a hangout for artists, writers and intellectuals, after the US Embassy opened for business in 1946 in the old Palazzo Margherita, the street became the heart of an unofficial American colony, which the Yanks nicknamed “the Beach”.

By the end of the 1950s, it boasted a Harry’s Bar and a Café de Paris, establishments already existing in cities favored by jet-setters, and the airline TWA began operating direct flights between New York and Rome. The city’s status as a glamorous destination was sealed; and Via Veneto was the hub of a neighborhood where visiting Americans, especially wealthy ones staying in luxury hotels, might feel at home.

As for movies, the genesis of La Dolce Vita was rooted in a pragmatic business decision. The Italian government, like others in Europe, was alarmed by the overwhelming post-war success of Hollywood films and passed legislation to defend its film industry in a number of ways. These included a strategy known as “blocking” funds earned in Italy by American films, insisting they could only be spent in the country where they were earned.

Hollywood studios circumvented this by making films abroad, using blocked funds as their budgets. Italy was a beneficiary of this gambit: it boasted a reliable climate for uninterrupted shooting, and great locations including beaches, coastlines and the glories of Rome. Above all, it had Cinecittà (Cinema City), a world-class film studio conveniently situated on the outskirts of Rome. Opened in 1937, the dream factory was Mussolini’s brainchild (something Italians are still a little sheepish about). Il Duce grasped how potent moving images could be for propaganda, and resolved to make Cinecittà the equal of Hollywood studios. This was a dictator who genuinely loved movies (he founded the Venice Film Festival); with Cinecittà, he effectively created a viable film industry for Italy.

So it was that 20th Century Fox shot Prince of Foxes, a medieval adventure story starring Tyrone Power and Orson Welles, wholly in Italy. On its release in 1949, it grossed enough money to make shooting Hollywood movies in Italy seem a shrewd idea. In its wake, MGM upped the ante, announcing an epic production of Quo Vadis, set in ancient Rome and starring Robert Taylor and Deborah Kerr. A huge production, even by Hollywood standards, it boasted a then remarkable budget of $7.6 million. Statistics about the film’s scale were bandied about by publicists. Some scenes used 30,000 extras, all of them job-hungry Romans. A record 32,000 costumes were designed for the movie. The production took over Cinecittà for a whole year.

Quo Vadis was such a big deal that, in June 1950, Time magazine ran a leading piece about it, and the significance of making American movies abroad (now known as “runaway production”). The piece was titled Hollywood on the Tiber, and the phrase quickly stuck.

If it seemed a risky proposition, it paid off. Quo Vadis went on to gross three times its budget in North America, and became the highest-grossing film of 1951. As a place for making Hollywood movies, Rome was suddenly hot.

And Hollywood kept on coming. The next big film was wildly different, but also advanced Rome’s credentials as a destination for Hollywood film-makers. Roman Holiday (1953) was a charming romantic comedy starring Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn. She played a princess, in the city on an official visit; she abandons her duties when she falls for Peck, playing a reporter who takes her sightseeing on the back of his Vespa (of course), taking in the Spanish Steps, the Colosseum and the Trevi fountain. Director William Wyler chose to shoot largely out in the streets, aware that the real city looked better than any backdrop the movies could devise. Thus, the film had three stars, Hepburn, Peck – and Rome, at its most ravishing.

No-one would argue that Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) was much of a movie. Its premise was paper-thin: three young American women, in town and looking for love, toss their loose change into the Trevi Fountain and make a wish. But it was a huge hit and its title song, crooned by Sinatra, topped the charts and won an Oscar. Rome? It looked as lustrous as ever.

Looking back, it feels as if Cleopatra (1963), a film that was a spectacle but failed to justify its absurdly expensive budget, was the high-water mark of the La Dolce Vita era. No bubble suddenly burst, but as the 1960s progressed, it seemed other cities (notably London) had seized Rome’s mantle. The Café de Paris moved out, as did Harry’s Bar.

They have since returned, and although Via Veneto is a less frantic street than in its heyday, it still has a real allure. It’s not hard to conjure up images from its illustrious past: a young Sophia Loren striding down the street, heading for the stardom that awaited her; Mastroianni, avoiding the gawping gaze of passers-by, and looking rueful; Ava Gardner, flashing her brilliant smile as she leaves a restaurant. And, of course, the ever-present paparazzi, jostling, shouting and waving, their flash guns popping. Times may change, but good stories never die.

Your address: The St. Regis Rome