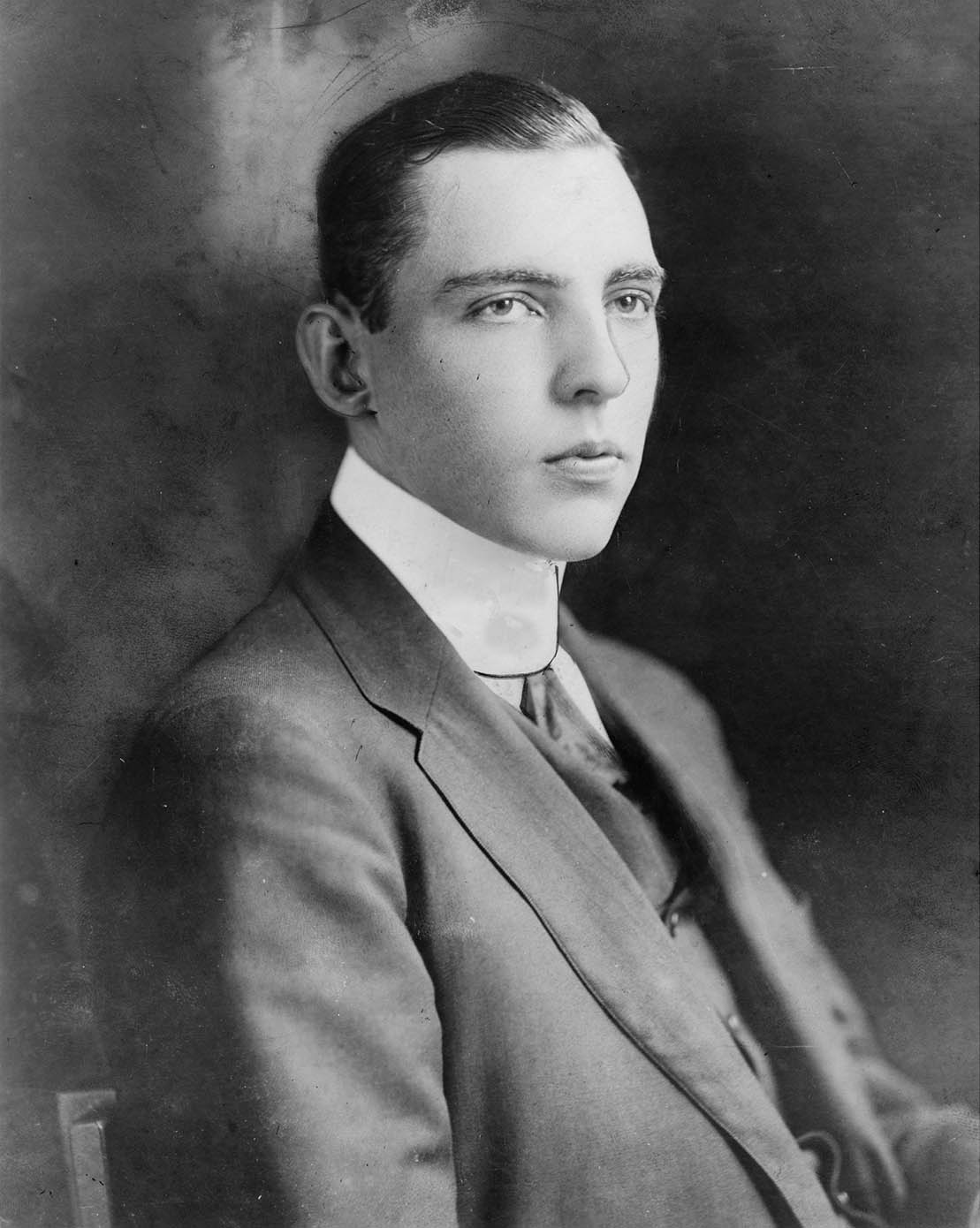

Every day, from when he was 20 years old, Vincent Astor slipped into his pocket the most valuable thing he owned: the watch used by his father, John Jacob Astor IV.

While personal heirlooms are normally of sentimental value to bereaved children, this watch was particularly precious. John Jacob had been one of the nation’s wealthiest men, and one of New York’s most keenly chronicled social figures, and the watch was in his pocket when he boarded the Titanic in Southampton with his young (second) wife, Madeleine, in 1912. Although Madeleine survived, John Jacob perished, and when his body was retrieved from the freezing waters and taken back to New York, the gold watch that had been in his pocket beneath his life jacket was presented to his son. It was never recorded whether the pocket watch still kept the time or if its hands were stilled, or even whether its numerals were still readable, having been immersed in water for days. But it remained in Vincent’s pocket for the rest of his life.

The two men had been extremely close. As the biographer Justin Kaplan writes in his book When the Astors Owned New York, “Vincent adored him and was adored in return”, obliquely referencing Vincent’s mother, Ava, who was unadoring, if not hostile, to both men. “Jack spent much of his time away from Ava in the company of their son... he was happiest sailing with Vincent on board Nourmahal, the steel-hulled steam yacht he had inherited from his pleasure-loving father.”

With the sinking of the Titanic, everything changed in Vincent Astor’s life. Having been a carefree undergraduate at Harvard, he suddenly became “the richest young man in the world”, with enormous responsibilities – and an empire to run. Alongside his father’s precious timepiece, $87 million cash and vast swathes of New York real estate, one of the most valuable items Vincent inherited was the St. Regis Hotel in New York City. An elaborately wrought and technically advanced building opened by John Jacob in 1904, it was, according to Frances Kiernan, an Astor biographer, “one of his proudest assets”.

There was much about the St. Regis Hotel to be proud. Architecturally, the Beaux Arts–style edifice was celebrated as much for its expertly articulated ornamentation as it was for the state-of-the-art engineering. As Robert A.M. Stern describes it in his book New York 1900: “The St. Regis [was] an accomplished design that used a vocabulary of ornamental details based on contemporary French practice to set a new standard for the luxury hotel.” The hotel’s general manager Rudolf M. Haan, wrote at the time of the opening of the 18-story hotel at Fifth Avenue and East 55th Street: “My hotel is not a place for billionaires only, but a hostelry for people of good taste who have the means to live as comfortably as they choose.” And the critic Arthur C. David said in a 1904 issue of Architectural Record that the elegance, grandeur, and domestic feel of the city’s finest townhouses “have been transferred to a hotel, and have in some respects been transcended”. He added that those who gravitated to the hotel were taken with the fact that it was “somewhat quieter and more exclusive” than other fashionable hotels.

When the hotel was first built, it was situated in what was then a decidedly upscale residential neighborhood, but was, as Arthur David put it, “plainly withdrawn from the ordinary places of popular resort”. By the time Vincent had inherited the hotel, however, it was a locus of New York society life, and its very existence had transformed the surrounding neighborhood into the city’s premier shopping area. Nevertheless, for reasons that remain unclear, Vincent sold the hotel to industrialist Benjamin N. Duke, who added the famous St. Regis Roof, with its elegant, frescoed dining room, and the Salle Cathay, both of which played host to some of the era’s most prestigious parties. By the early 1930s, however, Duke had allowed the hotel to lose its sparkle. In 1935, Vincent Astor regained control of the property through a mortgage default and immediately set about returning the St. Regis to its former glory. He modernized it, hiring the highly respected Anne Tiffany to redecorate, and made it financially profitable within just two years by placing his brother-in-law, Prince Serge Obolensky, on the executive board. La Maisonette Russe (formerly known as The Seaglades) became one of the most popular supper-nightclubs in New York. The Roof was turned into The Viennese Roof. The Iridium Room replaced the Salle Cathay and swiftly became one of the city’s hottest spots, complete with an ice-skating platform that rolled out from beneath the orchestra floor.

The hotel was a source of immense pride for Vincent. Although he was never a handsome man – who dressed in rather unimaginative suits, and was described by his mother as “stupid” as well as “clumsy and lumpish looking, with big feet” – he certainly understood the beauty of impressive buildings. He owned exquisite homes in Bermuda, Phoenix, Rhinebeck in upstate New York and Northeast Harbor, Maine – many of them considered among the finest houses in America. In the city, the building at 120 East End Avenue in which he lived with two of his three wives in the 23-room penthouse was considered one of the most luxurious apartment blocks of its day. But the most coveted of all of the homes he owned was a Manhattan townhouse he’d commissioned in 1927. The Regency-style townhouse on East 80th Street (now the headquarters of the New York Junior League) was so deep that it ran the full length of the lot to 79th Street and incorporated both a sunken garden and garage. It was, according to Robert A. M. Stern in his book New York 1930, a masterpiece, whose plan was “exceptionally gracious” and whose individual rooms were “delicately scaled”.

Real estate was in Vincent’s blood, and as well as creating beautiful homes for himself, he created vast housing projects across New York. Recognizing the increasing demand for upscale residences in Manhattan, he began to transform entire neighborhoods with new buildings, many of which still exist today. On East End Avenue, for instance, at the corner of East 86th Street, he erected fashionable and handsomely appointed Georgian-style apartment houses that still remain stolid fixtures in the neighborhood. Working together with Obolensky, he converted a row of Victorian-era brownstones between 88th and 89th streets into something he fondly referred to as “Poverty Row” (a reference to the fact that he envisioned young artists and professionals moving in who hadn’t yet made their fortunes in life, but would).

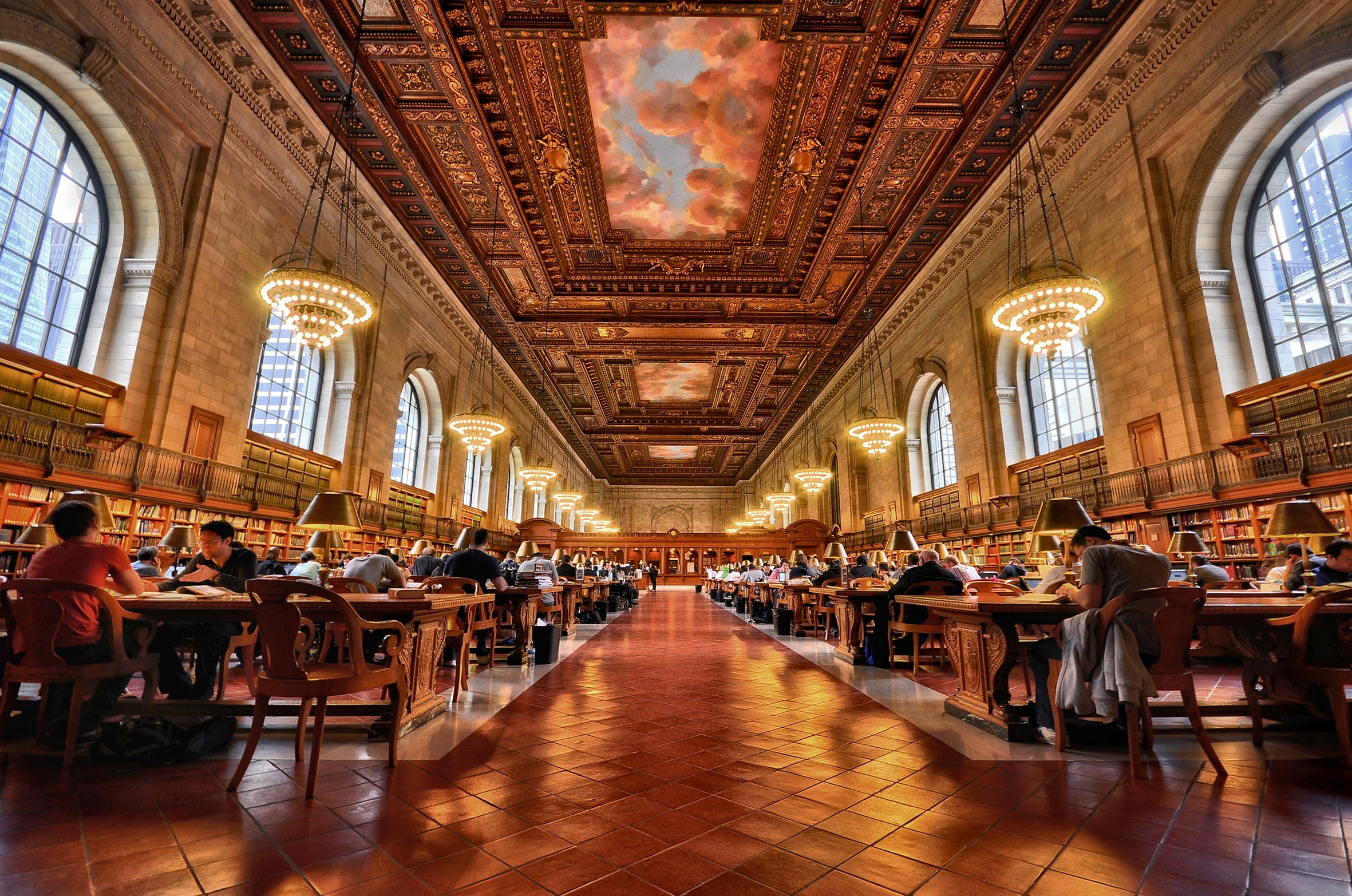

Not all of his life, though, was taken up with business – or mixing in high society. In fact, in marked contrast to his grandmother, who had established “The Four Hundred”, a collection of 400 members of American high society, Vincent was drawn to charitable rather than social causes. Despite the fact that John Jacob Astor, Vincent’s great-great-grandfather, had been one of the founders of the New York Public Library, the Astors were not especially famed for their civic or social generosity. In fact, prior to Vincent’s involvement, many of the apartments controlled by the family had devolved into slums – something the young man set about trying to put right.

By 1935, he had become instrumental in establishing America’s first managed housing project. Having sold a significant parcel of the Lower East Side to the New York City Housing Authority for less than half its market value, he built eight five-story walk-up apartments, meant to house poor and working families, many of them immigrants. On East 79th Street, he constructed housing for working people that, for the first time says David Patrick Columbia, co-founder of the New York Social Diary, took into consideration their health, “being constructed near water, with fresh air and ample space around them. He was sensitive in that way, very involved.”

Alongside housing projects, he funded youth projects at the New York Hospital and the American Red Cross, set up playgrounds and youth centers around the city, and built the Astor Home for Children in Rhinebeck, N.Y. “During his own childhood he was mistreated by his mother,” Columbia says. “So, as an adult he became extremely sensitive to the needs of children who were mistreated and needed love and attention.”

Given his relationship with his mother – and the fact his father’s second wife was only a year older than Vincent – it is hardly surprising that his private life was less successful than his business life. A man not known for natural bonhomie, nor interested in the activities required of his class, Vincent preferred to spend time sailing on the yacht he commissioned in 1927, a new Nourmahal, named after the vessel on which he and his father had passed such happy times. The 264-foot yacht, which he later donated to the U.S. Navy during World War II, boasted eleven staterooms, a dining room for 18 and a crew of 42. With its cruising range of 20,000 miles, the yacht allowed Vincent to travel the world for months at a time, even bringing home tortoises and other exotic specimens he found during his trips to the Galapagos and donating them to the Bronx Zoo. Back on dry land, while his successive wives continued to socialize at galas and fashionable functions, the biographer Kiernan notes that “Vincent went to the office every day. And when night came, he was a virtual recluse, wanting nothing more than to enjoy his dinner and relax by the fire.”

Of his three marriages, his last, to Brooke Astor in 1953, was perhaps the most successful. Unconventionally, the match had been set up by his second wife, Minnie. Vincent and Minnie’s marriage had long been over, but she agreed to divorce him only when she could find him a suitable wife. When Brooke’s previous husband died in 1952, Minnie arranged a dinner party, seating the widow opposite Vincent. Within weeks he had proposed.

By then, so astute was Vincent as a businessman, he had already doubled the family assets and initiated several notable ventures. One of these included providing the funds to merge Today magazine with a then defunct publication called Newsweek, to create a more politically progressive foil to rival Time. He became the famous magazine’s chairman from 1937 to his death in 1959. But perhaps his most dramatic and lingering financial undertaking was his establishment of the Vincent Astor Foundation in 1948, the goal of which was simply “the alleviation of human misery”. It was a big motto to uphold, but if any charity has come close to realizing that goal, it has been this foundation.

After his death in 1959, Brooke inherited $67 million to give to charitable causes: half the value of the estate. Until it was all spent in 1997, funding was given to countless institutions small and large: to dance troupes, the New York Public Library, neighborhood literacy programs, the Bronx Zoo (which built its monorail, among other features, with the grant money), the restoration of Bryant Park in midtown Manhattan, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Corporation, and the installation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Astor Court, a full-scale replica of a traditional Chinese garden and house.

Today, Vincent Astor’s legacy is present in so many aspects of New York life that the city would be unrecognizable without his munificence. Not only did he build neighborhoods that are mainstays of Manhattan and fund many of the city’s key cultural institutions, he also helped children gain access to good housing, recreation and education.

It is more than ironic that one of Vincent’s first heart attacks occurred as he was entering a theater in Poughkeepsie, New York, to attend a screening of A Night to Remember, a feature film that depicted the Titanic disaster. The story of his extraordinary life had come full circle.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Images: Getty Images, Pars International/Newsweek, Rex Pictures, Mary Evans Picture Library, Alamy