Twenty years ago, you would never have imagined that Dubai would one day possess a booming contemporary art scene attracting the world’s biggest players. Yet today, the annual Art Dubai gathering has become one of the most important events on the international art calendar.

It’s not just the scale of the event that has grown but also the number of women involved: nearly half the artists exhibited are now female, as are many of the Middle Eastern gallery owners and curators. Although in the business world men rule, according to her Highness Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, president of the Sharjah Art Foundation, who organizes a biennial in her emirate of neighboring Dubai, “as sons take over their fathers’ business interests, women are free to work in an industry they’re passionate about”.

Events at Art Dubai and the Sharjah Biennial have attracted well-informed and deep-pocketed audiences. This year at Art Dubai, 94 galleries representing 500 artists from 40 countries attended, as well as 95 museums. And during the week of Dubai Art Fair in 2015, more than $35 million changed hands for artworks from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, ranging from $10,000 to over $300,000.

Dubai is now an ideal spot to buy works by local and international artists, as well as to find talent for future exhibitions. Today, Nadia Kaabi-Linke’s Flying Carpets, a steel grid sculpture suspended by rubber threads at Art Dubai in 2011, hangs in the Guggenheim in New York. The Qatari-American filmmaker Sophia Al Maria has a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art until October 2016; the 92-year-old Turkish poet and artist Etel Adnan is exhibiting at the Galerie Lelong in Paris and Dubai; and the late Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi’s solo show opened the new Met Breuer exhibition space in New York this year.

Here we profile four leading women who have put Middle Eastern art into the frame.

Myrna Ayad

The Fair Director

Art Dubai’s new fair director is an important player in the Middle Eastern contemporary art world. Born in Beirut in 1977, she has lived in the UAE for 30 years, editing the art magazine Canvas and publishing daily newspapers during Art Dubai that introduced the Western art world to some of the most exciting conceptual art in the Middle East.

Unsurprisingly, Ayad has an address book that reads like a Who’s Who of the art world. The royal families in Saudi Arabia, Iran, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates have all opened up their private art collections for her to write about, and before joining Art Dubai in 2016, she consulted on cultural strategy for luxury labels from Bulgari and Chanel to Mercedes.

Art Dubai, she says, is “a pulsating power-house... and a gathering of people who rarely have a chance to meet. Saleh Barakat of Beirut’s Agial Art Gallery once told me, ‘Coming here, I see everybody’ and I very much identify with that.” This year she met artists, curators, collectors and heads of galleries and museums from all over the world, from Princess Wijdan Al Hashemi of Jordan who founded the Jordan National Gallery in 1980 to Germano Celant, who is curating the Kienholz: Five Car Stud show at the Prada Foundation in Milan.

Although the number of women running galleries has increased, they have always been influential in the Arab art world, she says. Pioneers included Mouna Atassi and her late sister Mayla, who opened a library/gallery in Homs in Syria in the 1980s, Farida Sultan, whose eponymous gallery was established in Kuwait in 1969, and Princess Jawaher Bint Majid Bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud, who established Jeddah’s Al Mansouria Foundation for the Arts in 1988. She concedes, though, that the interest in the region’s art has increased substantially, partly as a result of the displacement of people, and the growth of the Arab diaspora. “Art in the region is highly prized but historically there have been, and still are, spells when conflict halts artistic and cultural activity. Living in the diaspora means that people are attuned to other cultures and generally have greater sense of community and collective vision, as well as more emotional attachment and pride in the creative output of their respective communities.”

Diana Al-Hadid

The Artist

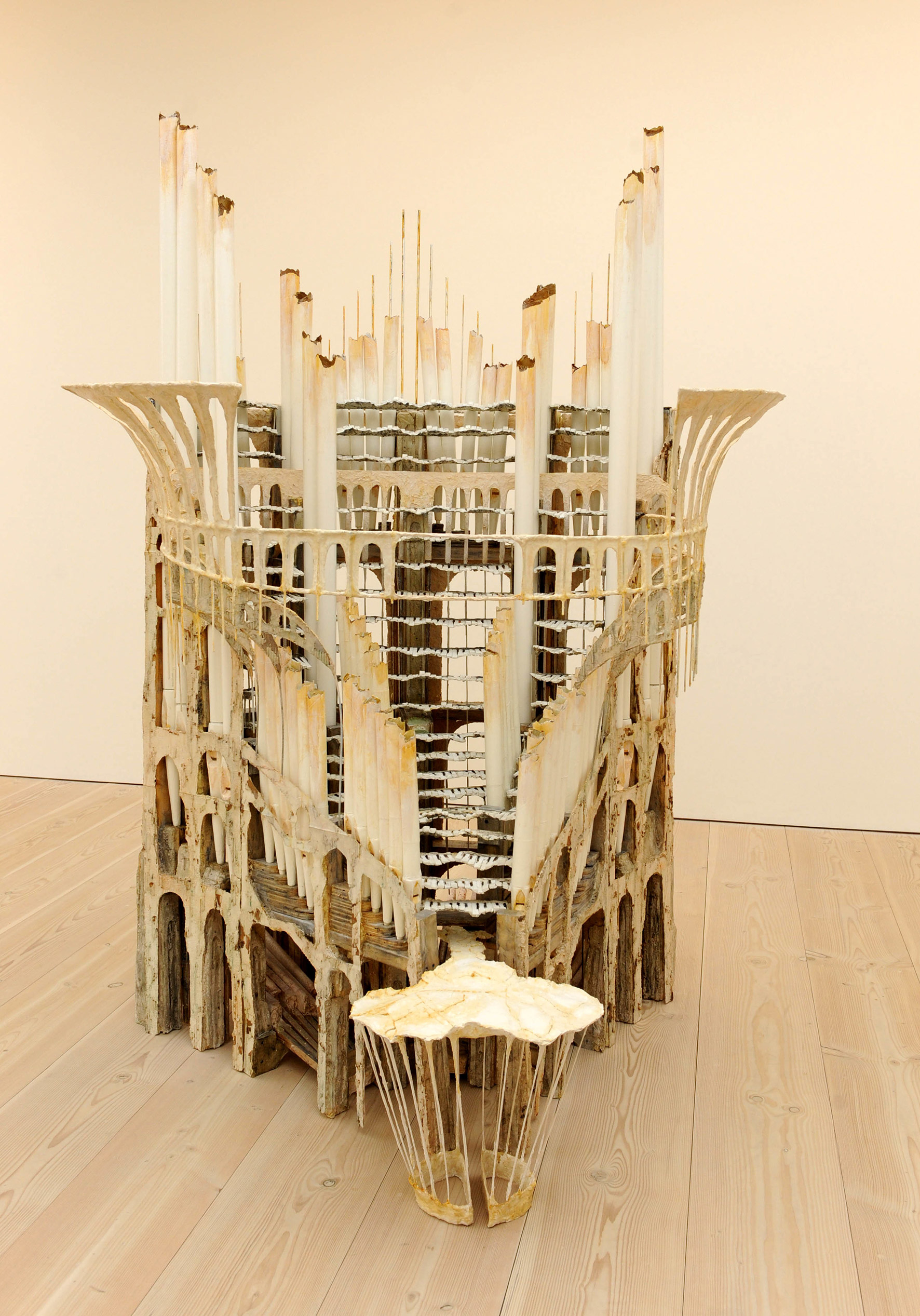

Born in Aleppo, Syria, Diana al-Hadid moved with her parents to Cleveland, Ohio when she was seven and used art, she explains, to make sense of her new world. “I was a real immigrant kid and didn’t speak English, and couldn’t read or write. My grandmother told me to draw hands and people and soon I became known as the weird kid who was always drawing.”

Fast forward a few decades, and the 34-year-old U.S.-art-college-educated, Brooklyn-based sculptor, who creates works using everyday materials from polymer and fiberglass to wood and steel, has become one of the most sought-after of her generation, and among the youngest to be represented by New York art dealer Marianne Boesky. During Art Dubai this year, Boesky sold seven of Al-Hadid’s sculptures to Middle Eastern collectors before the artist’s first major solo show, entitled Phantom Limb, took place at the New York University in Abu Dhabi.

Her punchy titles accompany powerful images. Phantom Limb – the phrase used to describe the sensation amputees sometimes feel of still having their lost limb – consists of white paint and gypsum dripping from formal plinths like stalactites, supporting a limbless and headless torso. Another, Fool’s Gold, features a reflective pool of shattered mirror atop three stacked blocks, from which dribbles of gold run out before reaching the floor. Both sculptures reveal an ultimate fragility and sense of loss, as the paint, canvas or gold just melts or trickles away.

Maya Allison, curator of Phantom Limb, believes Al-Hadid’s sculptures have “a visceral presence that channels some ancient, shared artistic memory. This mix of historical references and creative immediacy brings many different audiences into dialogue with her.”

Her vision clearly resonates all over the world. The David Winton Bell Gallery at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, is showing a selection of her works until October 30, 2016; the city of Nara in Japan has commissioned her to make an artwork for their temple; and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London has a maquette for her sculpture planned for the main courtyard.

Isabelle van den Eynde

The Gallery Owner

In 2006, Isabelle van den Eynde was one of the first people in Dubai to show contemporary art, and in 2010, when a new art district started to grow in the gritty industrial Al Quoz site, she immediately moved her eponymous gallery there. Today, the warehouses and marble-cutting factories have been colonized by artists, designers and gallerists, and the burgeoning loft scene recalls New York’s SoHo in the 1970s and 80s.

She specializes in Middle Eastern art that represents, she says, “the voice of our region”. For Art Basel Hong Kong in 2015, she featured Hassan Sharif, who uses discarded materials to create artworks. His Cotton Rope No. 7 (2012), an Arab dictionary tightly bound with rope, was bought for the permanent collection of the M+ museum when it opens in Hong Kong in 2019.

She also represents two of the 17 artists represented in But a Storm is Blowing From Paradise at the Guggenheim in New York until October 5, 2016. Rokni Haerizadeh’s 2014 artwork, which lends its name to the exhibition, uses news clips overlaid with ink, watercolor and gesso to transform humans into animal hybrids, while Mohammed Kazem’s Scratches on Paper visually represents sounds by scratching and gouging paper with scissors. To van den Eynde, these works represent many of the social and political concerns facing the Middle East: “They make a permanent statement that goes beyond our lives.”

Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi

The Curator

Royal mover and shaker Hoor Al Qasimi is an international force in the art world as president of the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), set up by her ruling father, Sheikh Dr. Sultan bin Mohammed Al Qasimi. A graduate of the Slade School of Fine Art in London, with a further MA in Curating Contemporary Art from the Royal College of Art, she speaks an impressive seven languages (English, Arabic, French, German, Japanese, Mandarin and Russian) and curated the UAE pavilion to showcase Emirati artists at the 2015 Venice Biennale.

At home, Sheikha Hoor shows contemporary art in the most extraordinary places restored by SAF, including the Ice Factory in the coastal fishing town of Kalba, an abandoned 1970s cinema nearby, and a UFO-shaped building in Sharjah called the Flying Saucer, which was first opened in 1978. An old Arabic house in the center, made from silky white coral-stone, has been turned into the Bait Al Serkal gallery.

Unlike many curators, Sheikha Hoor sees herself primarily as an artist, and then as a curator, which is why her exhibitions tend to be more emotive experiences than archival. “I look at the role through the eyes of a painter,” she says. “When a person enters the space, something has to lead the eye. Composing the room, in the same way that you would compose a photograph, is very important.”

The 11th edition of Art Dubai (artdubai.ae) runs from March 15-18, 2017, and the 13th edition of the Sharjah Biennial (sharjahart.org) starts in March 2017

Your address: The St. Regis Dubai

Images: Abbi Kemp, Juliet Dunne, Corbis via Getty Images, Getty Images