She had achieved this unchallenged position partly through her own personality and ambition, and partly with the assistance of the man who became Grand Vizier to her Sultana. This was Ward McAllister, a socially ambitious southerner who had realized that unless steps were taken to mold society into an acceptable model, it would be overwhelmed by the flood of new money now pouring into New York.

McAllister had managed to blend the old and the new by the simple expedient of picking what he and a coterie of friends saw as the most socially desirable from both groups – half a dozen each of the Knickerbockers and the most presentable Bouncer men – with these 12 as “patriarchs” launching a series of exclusive dances, with tickets strictly limited. Their exclusiveness made them an immediate success and the struggle to acquire tickets to these events was intense and often bitter, as only those who passed stringent criteria made it. And in Caroline Astor he saw the only person fit to rule this new élite.

Caroline’s great asset was her dignity, closely followed by her discretion – she is never known to have made a controversial remark. She could be friendly, but never intimate, and she never confided. Another woman might have found it difficult to live down the behavior of a husband such as Caroline’s, for William Backhouse Astor was known to be a heavy drinker and an even more voracious womanizer.

Fortunately, both of these pursuits largely took place at sea, as he spent much of his time aboard his yacht, The Ambassadress (at that time the largest private yacht in the world). As rumors of boatloads of chorus girls and a hold full of whiskey swirled around New York, Mrs Astor would smile serenely and remark – if anyone dared ask about him – that the sea air was so good for dear William, while regretting that she could not accompany him as she was such a poor sailor herself. For what Mrs Astor did not want to see, she did not see.

In person, she was of medium height, plump, plain and olive-skinned, with black hair (later a black wig) and smallish gray eyes that missed nothing. She favored dark colors – usually black but often a regal purple – and wore her diamonds rather as an idol bedecked for worship. At one dance, for instance, a diamond stomacher glittered on her blue velvet dress, in her black hair was a diamond tiara with diamond stars, several diamond necklaces studded with immense collet diamonds hung round her neck, clusters of diamond bracelets wreathed the wrists of her long white kid gloves and from her ears hung long diamond drop earrings.

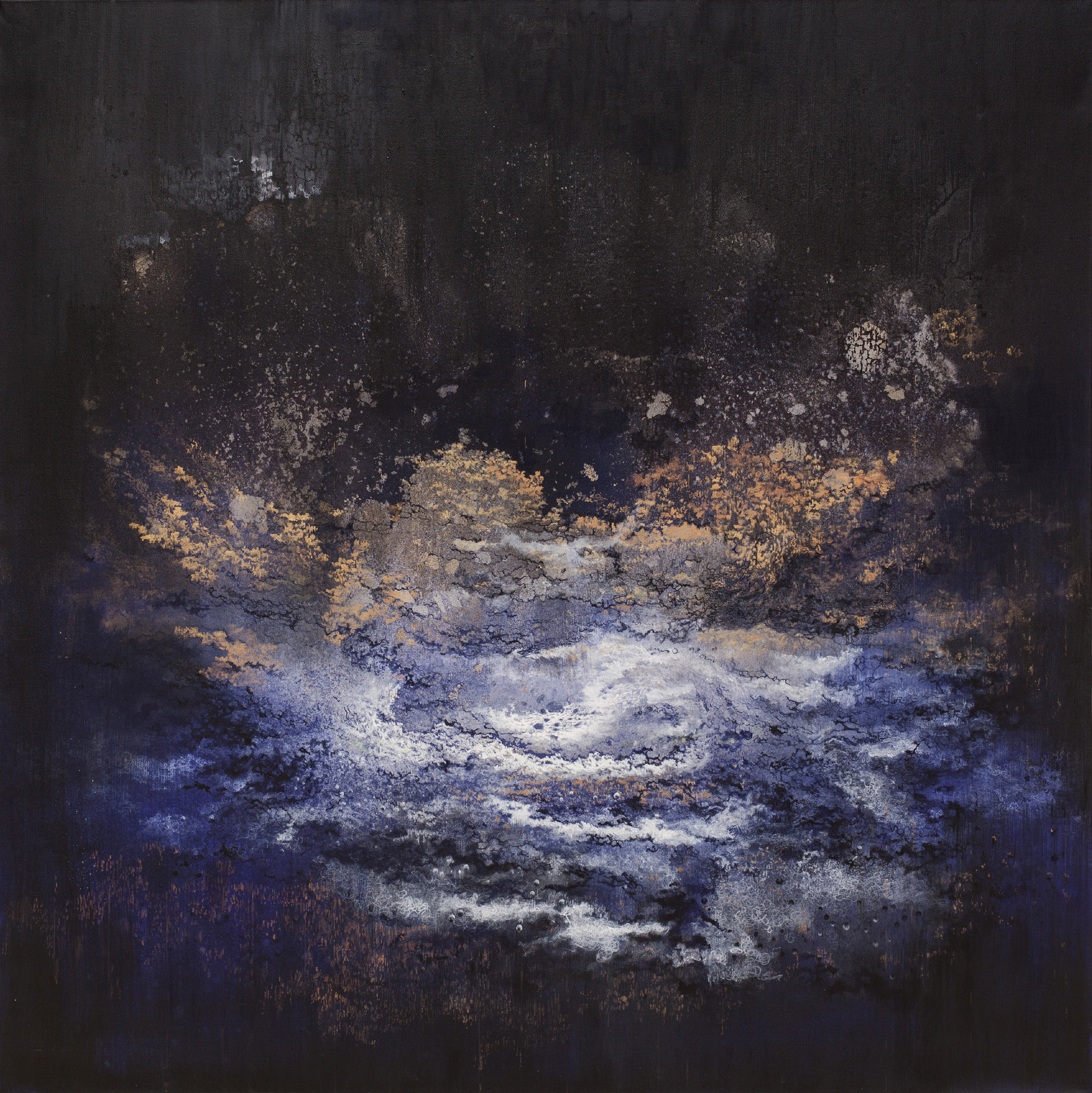

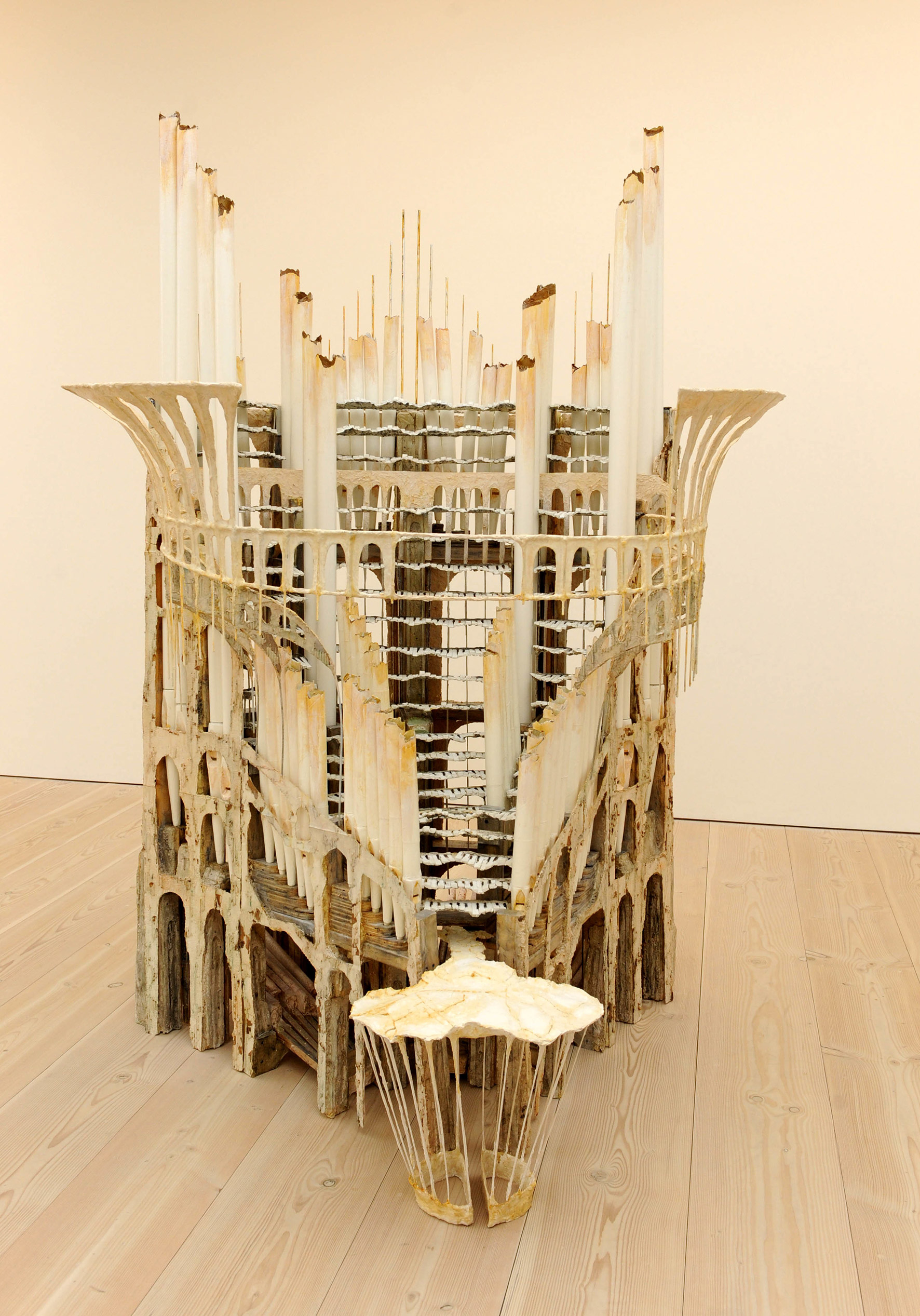

The years of Caroline’s reign were known as the Gilded Age, so immense were the fortunes made and spent. In the huge mansions along Fifth Avenue were marble mantelpieces, Gobelins tapestries, bronzes, sculptures and paintings swept up from Europe, oriental carpets, crystal chandeliers and French furniture. Between four and five of a summer afternoon, elegant carriages drawn by glossy horses carried women in silk dresses and elaborate hats, bowing as they passed each other; in the winter there was the same parade in horse-drawn sleighs in Central Park. At parties, the house smothered with flowers, the favors were antique ivory fans, gold snuff boxes or sapphire stock pins, with hundred-dollar notes stamped with the host’s name wrapped round the cigarettes by each place.

But the highlight of the entire social year was Caroline Astor’s ball. Its keynote was lavishness and ceremony – you did not go there to enjoy yourself, but to be seen there. The huge mansion, filled with flowers, blazed with light, and the specially favored were invited to sit with Caroline on the red velvet sofa from which she surveyed the ballroom.

At her parties there was often another lavish and unusual feature – a midnight supper. The dancing would be stopped, little tables would appear as if by magic (probably via an elevator in her son John Jacob “Jack” Astor’s house next door; the two houses could be interconnected when necessary) and a sumptuous supper would be served by servants in green plush coats and white breeches, their buttons sporting the motto the Astors had bestowed upon themselves: “Semper Fidelis”. After this, some guests would go home, others would continue dancing and the night would end with the more traditional early morning supper.

Bouncer women outside Mrs Astor’s sacred circle of acquaintance would go to any lengths to acquire an invitation, pleading through a third party, trying to persuade Ward McAllister they had a grandmother of impeccable lineage and, of course, giving dinners, musicales and dances themselves, which were duly written up in the social columns of the day.

Others, to avoid the stigma of not being asked, would get their doctors to prescribe a trip into the mountains for their health’s sake or go to the even greater length of leaving the country – after all, it sounded much more elegant to say: “I’m taking my daughters to be educated in France,” than “Mrs Astor hasn’t asked me to her ball.” They felt the Astor ban with double force when it came to launching their debutante daughters, for going to the same dancing class as the children of the Astor circle did not mean you got asked to the same balls later.

But the excluded wives of the nouveaux riches quickly discovered that in Europe these daughters could lead to a “back door” way into the Astor set. Beautiful, superbly dressed and hugely rich by European standards, such girls were sought-after brides among indigent aristocrats – in England, a succession of bad harvests, loss of labor to industrialized cities and the import of cheap grain had halved the income of most landowners. And even Mrs Astor would not refuse to receive the mother-in-law of a marquis. As I discovered when writing my book The Husband Hunters: Social Climbing in London and New York, in the period between 1870 and 1914, 454 American girls married titled Europeans, one hundred of them British aristocrats, with 60 of this hundred marrying eldest sons – a phenomenal amount by any standards.

Staying at or near the top was a constant struggle. Even in the Astor clan there was in-fighting. For years, Caroline’s nephew, William Waldorf Astor, fought a running battle with his aunt to try and position his wife Mamie as the Mrs Astor – after all, he, William Waldorf, was the eldest son’s eldest son, so his wife should hold this position by right. But nothing could dislodge Caroline, even when William Waldorf had his father’s house torn down and replaced by an enormous hotel, designed to overshadow his aunt’s mansion beside it. Her only comment was the icy put-down: “There’s a glorified tavern next door.<” Eventually, in disgust, William Waldorf left the US for England in 1891, saying that “America is no place for a gentleman”.

“I know of no art, profession or work for women more taxing on mental resources than being a leader of society,” said Alva Vanderbilt, who would become just that by dint of being one the few people to outwit Caroline Astor on her own ground. Her first step was building an enormous mansion on Fifth Avenue and filling it with treasures. Then she announced that she would give a housewarming costume ball, with the guest of honor her great friend Consuelo Yznaga, now married to the Duke of Manchester’s heir, Lord Mandeville. Society, avid to see inside the new house and meet a future duchess, eagerly accepted her invitations. It would be a splendid evening, with guests decked out as mandarins or 18th century courtiers – as shown in the photographs taken on the night, which are now in the collection of The Museum of the City of New York.

Suddenly Caroline Astor, accustomed to being asked to everything, realized she did not have an invitation – and her beloved daughter, who had been practicing her cotillion for months, would be unable to perform it. When she let this be known, Alva, like Mrs Astor educated in France and conscious of the niceties of etiquette, declared that she could not make such an approach to Mrs Astor because the rule was that the senior lady must first have called on the junior one.

At once, Mrs Astor dispatched her footman to leave a card on Alva and, almost by return, an invitation was sent down Fifth Avenue. Mrs Astor attended the ball, saying afterwards: “We have no right to exclude those whom the growth of this great country has brought forward, provided they are not vulgar in speech and appearance. The time has come for the Vanderbilts.” They were in.

It was not until 1902 that Caroline Astor was finally toppled. Her nemesis was 32-year-old Grace Vanderbilt, originally one of her protégées, who outflanked her in a ruthlessly cunning move that resulted in Grace, rather than Caroline, entertaining the Kaiser’s popular younger brother to dinner. It was the coup de grace and Caroline knew it. The shock wave traveled around New York and, like all those women who had tried and failed to receive an invitation to her ball, she left for Europe.

Or, as the gossip magazine of the day gleefully put it: “Mrs Astor will sail before the dinner takes place.”

The Husband Hunters: Social Climbing in London and New York is out now, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Your address: The St. Regis New York

![[Art Gallery in the Astor Mansion, 34th Street and 5th Avenue.]](https://magazine.stregis.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/X2010.11.4462.jpg)