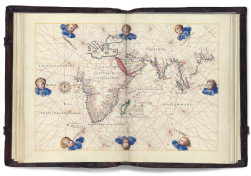

Breaking down barriers is what jazz is all about – music that lives and breathes collaboration and assimilation, both instrumentally and culturally. Aptly, the great melting-pot of New York City is jazz’s spiritual home – the center for swing in the 1920s, bebop in the 1940s, avant-garde in the 1960s and the loft scene of the 1970s that created world-famous venues such as The Cotton Club, Birdland and The Village Vanguard. Musical movements may come and go, but jazz continues to thrive in NYC as new generations discover, absorb and renew the genre.

And central to this participation is Wynton Marsalis’s ground-breaking Jazz at Lincoln Center, part of the famous arts venue and a hub for jazz education and performance since 1987. In the spirit of the great jazz ambassadors of days gone by – Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington and the recently departed Dave Brubeck – Jazz at the Lincoln Center has extended its reach to the Middle East and teamed up with The St. Regis Doha to open its first club outside New York – a partnership that flows naturally from The St. Regis New York’s longstanding connection with the genre, having hosted celebrated performances by the greats, including Count Basie, Buddy Rich and Tommy Dorsey, from the first Jazz Age up to the present day. Its spirit will be heard in upcoming performances from virtuoso trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who is the program’s director, and from pianist extraordinaire Ahmad Jamal, bass wunderkind Christian McBride, drummer Willie Jones III and new vocal talent Cécile McLorin Salvant. An astonishingly bright and nimble trumpet player, 51-year-old Marsalis has been thrilling jazz audiences since his appearances with legendary drummer Art Blakey at the age of just 19.

A proud New Orleans native, Marsalis has been the jazz figurehead for his generation and the next. “Throughout its history, jazz has connected with different cultures, races, religions and generations,” he says. “This is an especially important time to communicate the sanctity of our collective human heritage. Jazz is a perfect tool to do this.” Marsalis, one of the key contributors to Ken Burns’s famous Jazz documentary series of 2001, is also a gifted and respected teacher, and in his role as artistic director of New York’s Lincoln Center he is passing on all he’s learned to the next generation of jazz greats. His recording career, now spanning 30 years, includes the Pulitzer Prize-winning Blood on the Fields and his legendary eponymous 1982 debut album featuring Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams. The St. Regis Doha may not seem the obvious setting for a jazz club, but walk through the wooden doors on the fourth floor and you could be in The Village Vanguard or Blue Note. The sightlines and acoustics are perfect. Marsalis approves: “I grew up in clubs – I know what clubs should be like, and this is beautiful. Our goal is to uplift everyone who hears us.”

Your address: The St. Regis Doha; The St. Regis New York

Images by Corbis, Max Reed, Ayano Hisa & Hanayo Takai, Anne Webber

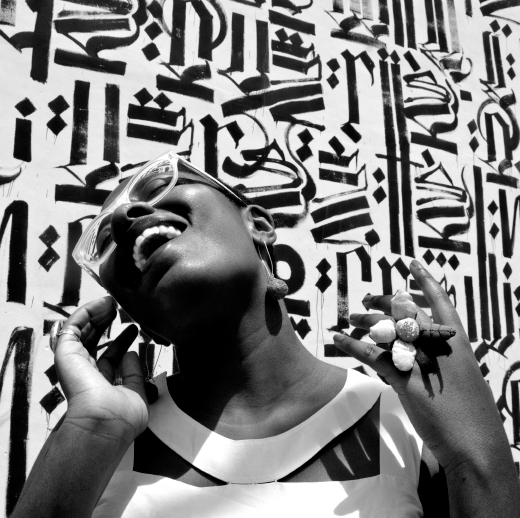

Cécile McLorin Salvant

Hailed as one of the most gifted jazz vocalists to emerge on the scene in recent years, 23-year-old Cécile McLorin Salvant was born and raised in Miami, Florida, by her Haitian father and French mother. She regularly wows audiences with her huge range, incredible control, advanced melodic sense and intriguing repertoire that draws on everything from Erik Satie to John Lennon. Critics have been comparing McLorin Salvant to Sarah Vaughan, Abbey Lincoln and Carmen McRae. In 2010, she won jazz’s most presigious award, the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, which recognizes the next generation of masters. She spent August 2012 recording her eponymous debut album for the thriving Mack Avenue label, and has been performing as Wynton Marsalis’s special guest with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. Don’t miss one of jazz’s brightest young stars.

Ahmad Jamal

Jamal is a hugely innovative and influential pianist, one of the giants of post-war jazz. His sense of space and conception of rhythm was a significant influence on Miles Davis, and his trio is one of jazz’s most enduring small groups. You can hear the whole history of the piano in his masterful, effortless playing, from Earl Hines and Erroll Garner through Keith Jarrett, right up to Brad Mehldau. A child prodigy, he was tipped for greatness at the age of 14 by the legendary Art Tatum. Jamal has been at the forefront of jazz piano for five decades, and recently released his studio album Blue Moon. Now, at the age of 82, Ahmad Jamal continues to thrill jazz audiences worldwide with his Zen-like solos, and is rightly considered one of the all-time greats.

Christian McBride

McBride’s vitality, virtuosity and pure love of jazz have given the acoustic bass a new lease of life, and in doing so he has also joined the pantheon of greats alongside the likes of Milt Hinton, Ron Carter and his idol Ray Brown. Musicians joke that there’s nothing Christian McBride can’t play – he’s equally at home cranking up the jazz/rock with Chick Corea, burning with Sonny Rollins at Carnegie Hall or arranging and composing music for his own big band. Still only 40 years old, McBride has released ten acclaimed albums, including the Grammy winner The Good Feeling and Conversations with Christian, a joyous collection of duets with the likes of Sting, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Hank Jones, Dr. Billy Taylor and George Duke. Don’t miss this chance to check out one of the young giants, and arguably the most important jazz bassist since Jaco Pastorius.

Willie Jones III

We’ve all heard the old saying: a band is only as good as its drummer. Taking his cue from past masters Philly Joe Jones, Billy Higgins and Art Blakey, Willie Jones III, born in LA in 1968, knows exactly how to drive a band with his inventive sense of swing, slick grooves, subtle dynamics and natural power. Utilizing a very small kit, Jones has always been in huge demand, performing with the likes of Herbie Hancock, Horace Silver and Milt Jackson. He co-founded the innovative Black Note band in 1991, which regularly served as Wynton Marsalis’s opening act, and won the coveted John Coltrane Young Artist Competition in 1991. Initially inspired by his pianist father, and later studying under the legendary sticksman Albert “Tootie” Heath, Jones understands jazz music inside and out. Soloists adore his playing – he’s a drummer to silence drummer jokes forever.