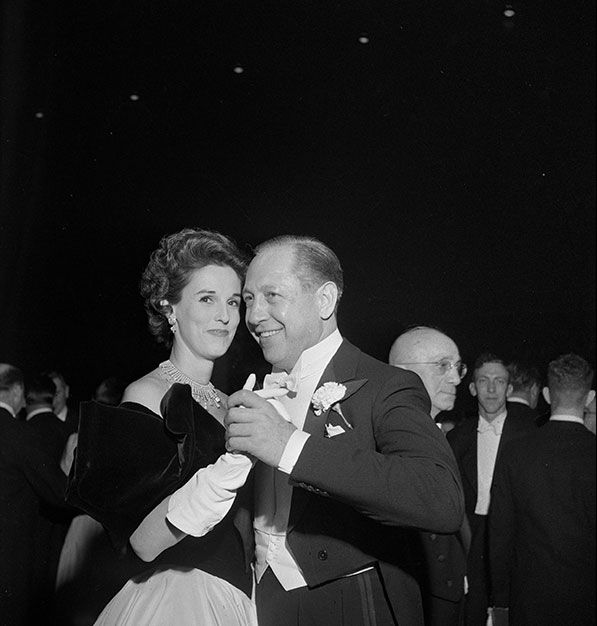

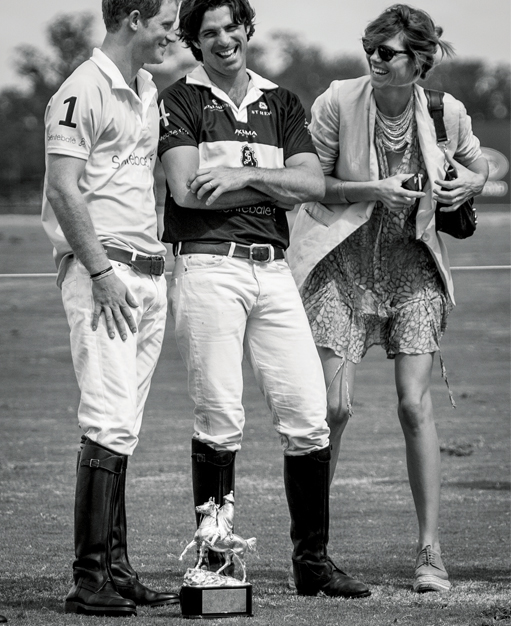

Twentieth-century New York was full of fashion role models: high-society ladies whose wardrobes were as stylish as any European aristocrat’s, whose jewelry was priceless and whose elegance was the result of years of devoted attention. But none had quite the grace of Babe Paley.

Babe was the style icon of her day. The leader for a decade of the Ten Best Dressed list and an inductee into the Fashion Hall of Fame, she was a friend of and hostess to some of the most famous people in America. Babe was part of a circle alongside supposed wartime spy Gloria Guinness, actress and fashion designer C. Z. Guest, Hollywood socialite Slim Keith, Marella Agnelli, wife of Fiat chairman Gianni Agnelli, and Pamela Harriman, daughter-in-law of Winston Churchill and a future United States Ambassador to France. Truman Capote (a friend until he wrote an unflattering, minimally fictionalized exposé in 1975 that severed their bond) called these elegant women “the swans”, due to their propensity to group and glide through society like graceful birds.

What made Babe stand out from the rest of the swans was her compelling presence. As her friend, jewelry designer Kenneth Jay Lane, put it, Babe Paley, like the Mona Lisa, had a face that was both memorable and elusive. Eerily attractive and supremely charismatic, she was a product of a time when society figures were household names – and when women were schooled to be the epitome of elegance.

“One look from Babe and you melted,” Lane says. “You fell in love with her the moment her marvelous eyes looked at you. Every waiter in every restaurant fell in love with her. She made you feel that she was in love with you. If she walked into a room, people didn’t quite stop breathing altogether, but they held their breath for a minute. She had an aura.”

She also knew how to live in supreme style. After her marriage to CBS founder William S. Paley in 1947, she established an estate, Kiluna Farm, on Long Island, where the couple spent weekends and guests included the likes of Lucille Ball, Grace Kelly and David O. Selznick. In Manhattan they occupied a magnificent suite at The St. Regis, which Babe remodeled with the help of society decorator Billy Baldwin. “I was in my early twenties when I first saw their apartment at The St. Regis,” recalls Lane. “It was a corner suite, and it had been tented by Baldwin. There was a wonderful birdcage chandelier hanging in the middle of the drawing room.”

As David Grafton, who wrote the definitive biography of Babe and her family, The Sisters: The Lives and Times of the Fabulous Cushing Sisters, describes the apartment: “Using yard upon yard of Indian cotton… Babe transformed the space into an exotic fantasy.” Later, when she and her husband moved into their 20-room duplex at 820 Fifth Avenue, while still keeping her St. Regis suite, Baldwin “recreated their old St. Regis living room, which he had installed originally as a jewel-like library”.

Babe didn’t have to work her way up in society. She was born into it on July 15, 1915, to Harvey Cushing, a pioneering brain surgeon, and his wife Kate, a gracious but determined society hostess in Boston. As Grafton writes, “Early on, the Cushing sisters learned to entertain and cater to the comforts of an eclectic mix of personalities, many of whom were masters of their own medical or social fiefdoms.” The late Millicent Fenwick, a friend of Babe’s and a New Jersey congresswoman, remarked, “Each of the girls, and especially Babe, entered the world convinced that they were the most attractive young women in the world, combining beauty and brains.”

Barbara was the youngest of the five Cushing children – hence her nickname, Babe – and she and her sisters were groomed from the start to marry well, a goal that became a virtual profession for their mother. Kate proved instrumental in engineering the 1930 marriage of her first daughter Betsey to James Roosevelt, eldest son of Eleanor and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Minnie would eventually marry Vincent Astor, Jr., who owned The St. Regis in New York.

In 1940 Babe married Stanley Grafton Mortimer, Jr., grandson of one of the founders of Standard Oil. She had been working at Vogue, less as a day-to-day line editor and more as one of the magazine’s legions of young, socially prominent women forging connections with designers of the day – the likes of Christian Dior, Coco Chanel and Cristobál Balenciaga. She was still at Vogue when the couple divorced in 1946, and she first met the significantly older, still-married Paley.

Their union in 1947 was, in some ways, unlikely, in that Paley, although powerful, was the son of Jewish immigrants – a detail that remained unsettling for Babe’s WASP mother at a time when such issues mattered among America’s elite. But with his intellect and contacts, and her social abilities, the couple became the hub around which high-society events revolved.

While powerful men need not be handsome or even charming, powerful women, especially in the mid-20th century, had to be beautiful. While Babe certainly possessed the beauty, she also had, as legendary interior designer Mario Buatta says, “substance and a sense of humor. I remember being at a client’s house for lunch one Sunday. Babe was at the table, about ten of us, and she was very quiet for some reason. But then she secretly put a piece of spinach on a front tooth. Finally, one of her friends at the table pointed it out to her. It got her the attention she wanted and it brought her into the conversation – a skill she never had any problems with.”

David Jannes, an art collector and former PR who handled some of New York’s most glittering society events, says, “You have to remember that Babe Paley and the women in her circle were true individuals. The society women of today don’t stand out in the way people like Babe Paley did. She dedicated her life to beauty – in her personal appearance, the objects she acquired, the people she surrounded herself with, the homes she made at The St. Regis and Fifth Avenue and elsewhere.”

The couple entertained CBS stars such as Edward R. Murrow, visiting dignitaries and politicians, and writers including Capote, who once famously said of his former friend, “Babe Paley had only one fault. She was perfect. Otherwise she was perfect.” Style was everything at their Fifth Avenue apartment. Sheets were ironed twice, once in the laundry, and once on the bed. Menus were archived to avoid serving the same meals to returning guests. Visitors complained of not being able to get into the bathroom because there were so many flowers. To cap it all, Paley had amassed a distinguished art collection, a centerpiece of which was Picasso’s Boy Leading a Horse (previously owned by Gertrude Stein, and which now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, a gift from Mr. Paley).

Much has been written about Babe and Paley’s troubled marriage, both then and subsequently. Paley was devoted to Babe and keenly aware of the cachet she brought him, yet he was also a conspicuous womanizer. “Bill was Bill

and she knew it,” says Kenneth Jay Lane, who maintained a close friendship with Paley after Babe’s death. “She adored him. He was a fascinating man and much of her role was to make him happy.” Yet Capote, quoted in Gerald Clarke’s biography of the writer, said, “I never met anybody who was so desperately unhappy as she was… Once she tried to leave [Bill] and I sat down and said, ‘Look… Bill bought you. It’s as if he went down to Central Casting. Look upon being Mrs William S. Paley as a job, the best job in the world.”

Throughout her decades-long tenure as a society leader, the embodiment of high fashion, and a fundraiser for her favorite charities, Babe also occupied a role that could only have existed in her day. Certainly to fashionable women in New York, but also to those in the far reaches of America, Babe Paley was a recognized name, the exemplar of style and grace. Such was her power that one warm day, upon leaving a Manhattan restaurant, she removed her scarf and tied it to her purse. Paparazzi recorded the moment and “in no time, women throughout America were tying scarves to their handbags,” recalls Grafton. “So great was Babe Paley’s charisma that women of all ages and from every walk of life would do nearly anything to emulate her. They wanted not only to look like her but to be like her.”