From the slums of Mumbai to the palaces of Rajasthan; from the technology hubs of Bangalore to the spiritual mecca of Varanasi, one common thread weaves its way through India: an enduring love of jewelry. No one sub-continent’s cultural, geological and historical makeup is so entwined in the sourcing, manufacturing and self-adorning as this great land mass – from the excesses of Mughal royalty to the traditional nose-rings, hand jewelry and stacked gold bracelets worn by millions. Characterized by yellow gold, strings of beads, carved emeralds and bold color-combinations, its influence in varying degrees has crept into Western jewelry design, a process that can be traced back to the early 20th century.

As the great jewelry houses of Paris – Cartier, Van Cleef and Boucheron – made stone-buying trips to India in the early 1900s, their paths inevitably crossed with the maharajas of the time who, seeking a more Western, refined aesthetic, commissioned the maisons to re-make their jewels, replacing the traditional yellow gold with finer, less visible, platinum settings. One of Cartier’s biggest ever commissions occurred in 1925, when the Maharaja of Patiala handed over his crown jewels for total re-modeling, a job that took several years to complete and proved key to an East/West cross-pollination of styles. The Indian tradition of long, beaded necklaces that covered the chest morphed into the fashionable sautoirs of the 1920s, while engraved emeralds (carved in Jaipur and often the centerpiece of ceremonial jewels) became a staple of the art-deco style running concurrent at the time.

Cartier incorporated these stones into a genre that’s still firmly part of their house style: Tutti-Frutti has carved, unfaceted emeralds, rubies and sapphires in leaf and fruit motifs set against the sparkle of white diamonds – a combination considered daring and avant-garde at the time. (Cartier has never stopped making Tutti-Frutti pieces; last year the house showed the largest piece in this style it had ever made: the aptly named Rajasthan, featuring a central carved emerald of 136.97 carats.)

Boucheron’s love affair with the Subcontinent started in much the same way. Its recent Bleu de Jodhpur high jewelry collection is a riff on the “Blue city”, mixing Indian motifs and materials (such as marble from the same quarry used for the Taj Mahal) with Indian jewelry styles, underlined with the ever-present sharp execution of a Place Vendôme jeweler. East meets West in a mix of ancient custom and contemporary savvy.

While Surat in Gujarat is famed for diamond cutting and the mines of Golkonda have produced some of the world’s most legendary diamonds, it is Jaipur in Rajasthan where the cutting of colored stones and the centuries-old techniques of enameling are still practiced.

Western jewelers such as Bulgari source many of their signature candy-bright gems from the ancient city, with creative director Lucia Silvestri making frequent trips to oversee the process. She concedes that these visits have informed the house’s rainbow palette. “I love the colors of the saris the women wear in Jaipur,” she says, “and how they clash orange and pink, blue and red, in unexpected combinations. It gives me fresh ideas for designs.”

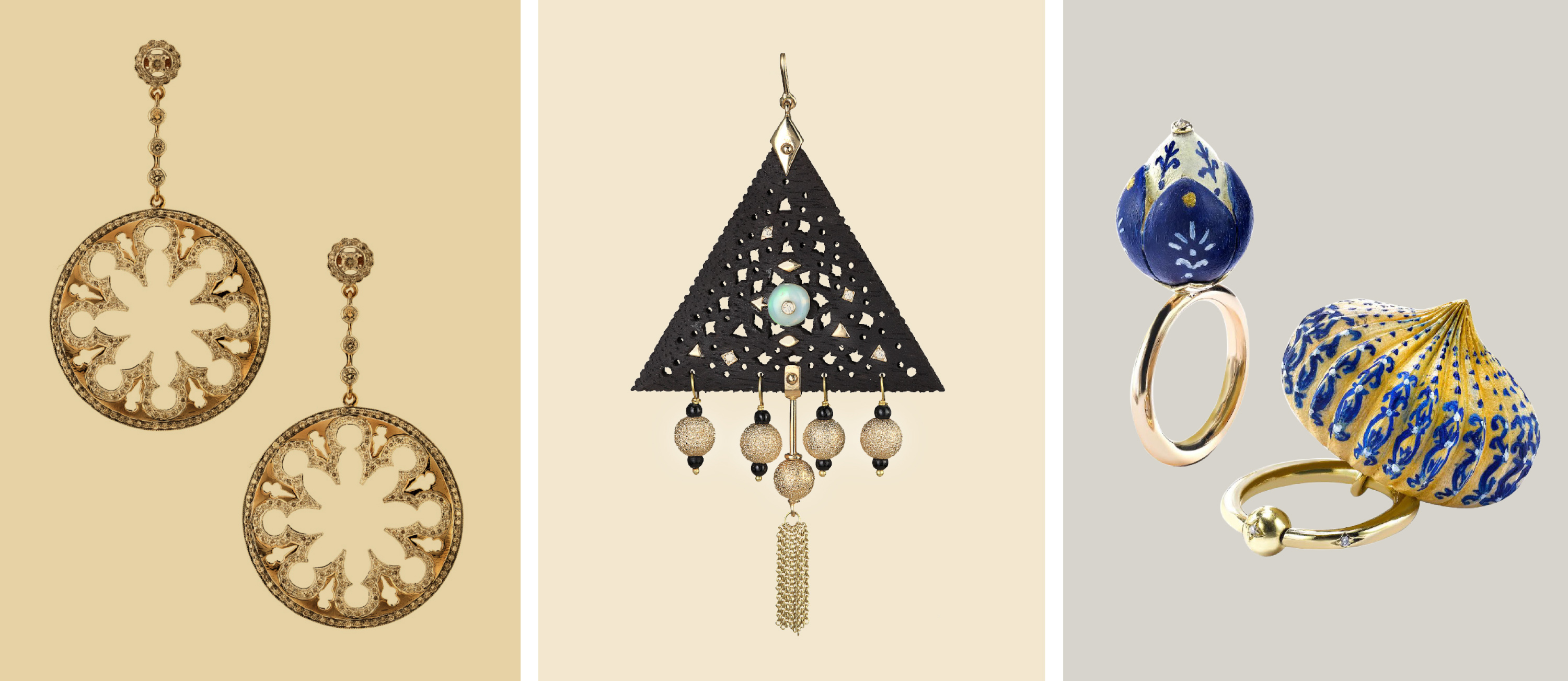

Less mainstream jewelers are also harnessing the centuries-old expertise of Indian workmen. Alice Cicolini, for instance, uses their enamel workshops to create exquisite hand-painted rings, and cult jeweler Noor Fares created her Navratna collection after a trip to Varanasi. Hanut Singh, great-grandson of the Maharaja of Kapurthala, who was a famous patron of Cartier, has spent ten years honing his signature fusion of old and new. Singh shows at private trunk shows and attracts a cult following from the likes of Madonna, Beyoncé and Diane Von Furstenberg.

Although India’s influence has always been present in the West, one development from a particular jeweler marks a significant change. Nirav Modi is the first Indian jeweler to combine Eastern motifs and themes in a thoroughly Western way. Unlike Indian brands like Amrapali, whose core designs are dominated by yellow gold and large colored stones that resonate with its Indian clientele, Modi has expanded his modern designs, attracting high-profile fans like Kate Winslet and Naomi Watts. Although his designs are Western, his Indian inspiration is still there. His Mughal range features diamonds cut to mimic petals, the shape inspired by 18th-century paintings of Mughal gardens. And his Maharani necklace with strings of emerald beads owes everything to its ancestral roots yet looks entirely at home in the window of his New York store.

Progression is everything; from an aesthetic that originated in the coffers of the maharajas to a style now gently disseminated throughout Western jewelry, India’s influence continues to dazzle, a century on.

Your address: The St. Regis Mumbai

Romancing the stone

Haut diamantaire Nirav Modi (niravmodi.com) blends Indian and Western influences to create exquisite pieces like his “Emerald Maharani” necklace (above) and his “Flamingo Embrace” bangle (below)

Fit for a Maharaja

Below, left and middle: “Gothikas” earrings and “Ebony Triangles”, both by Hanut Singh (hanutsingh.com). Below, right: Indian-made enameled pieces from Alice Cicolini (alicecicolini.com)