In 1927, the year that The St. Regis hotel opened its new wing and ballroom on 55th Street, a Jewish-German teenager left his home in Berlin to try to find work in New York and to pursue his love of jazz. At first he lived rough in Central Park, walking by the grand hotel to find work in the city’s docks. By 1939 he had founded Blue Note Records, the most iconic jazz label in the world and the epitome of style and cool. His name was Alfred Lion.

The city in which he arrived had already become the jazz capital of the world. The first jazz record had been cut there just before the end of World War I,

and soon after dozens of venues had sprung up all over the city, from grand ballrooms to tiny spaces. Besides well-known spots such as the Cotton Club in Harlem, where Duke Ellington made his name, a thriving underground scene had evolved around 52nd Street, where musicians gathered to experiment with the form – and imbibe a drink or two – in the small, smoky interiors. It was here that Lion hung out.

When he wasn’t in clubs, Lion spent a great deal of time at Milt Gabler’s Commodore Music Shop on 52nd Street, talking to the owner and his brother-in-law, Jack Crystal (the father of comedian Billy Crystal), who worked at the shop and helped run gigs at a nearby club. Gabler not only sold records but had his own label, which in April 1939 would put out one of the most important political records ever made: Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit, about the lynching of black men in the Southern states.

Alfred Lion’s new Blue Note label had released its first 78rpm disc a month earlier, and while it didn’t have the political resonance of Gabler’s release, it had arguably just as significant an impact. In the last days of 1938 Lion had gone to a landmark concert at Carnegie Hall, showcasing black music from spirituals to swing, and then had been a guest at the opening of Café Society, the first club in the city in which blacks and whites were treated as equals, greeted at the door with the words “Welcome to Café Society, the wrong place for the right people”. Having spoken to Gabler, he suddenly knew what he wanted to do: get boogie-woogie pianists Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis to make some recordings.

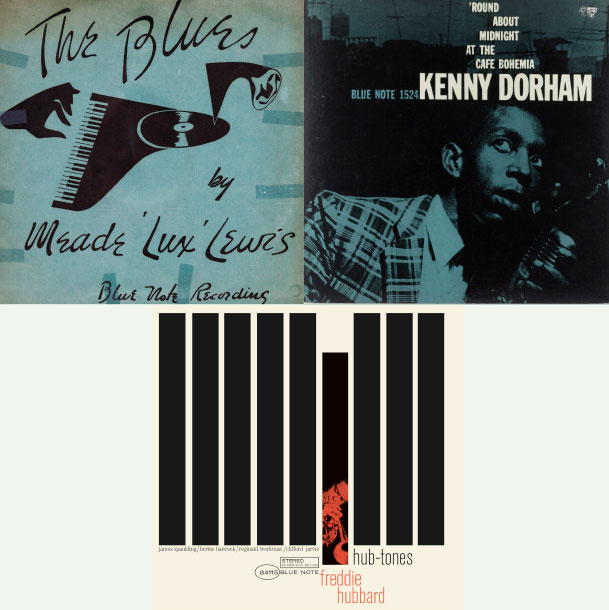

In those days, very few records were pressed – and when they were, artists often weren’t paid. So when Lion spoke to the artists, and promised not only to pay them, but to pay them well, the deal was sealed. A studio was booked on the West Side of Manhattan, a bottle of whisky was procured, and Ammons and Lewis performed a series of solos and duets. At the end of the session Lion didn’t have enough money to cover both the studio time and his artists, and had to return some weeks later for the masters. When he listened to the discs back at his apartment, his life was changed: “I decided to go into the music business.” He pressed 25 copies each of BN1 and BN2, the former featuring two slow blues tunes, and the second two boogie-woogie numbers. With no distribution in place, he offered them by mail order at $1.50 each.

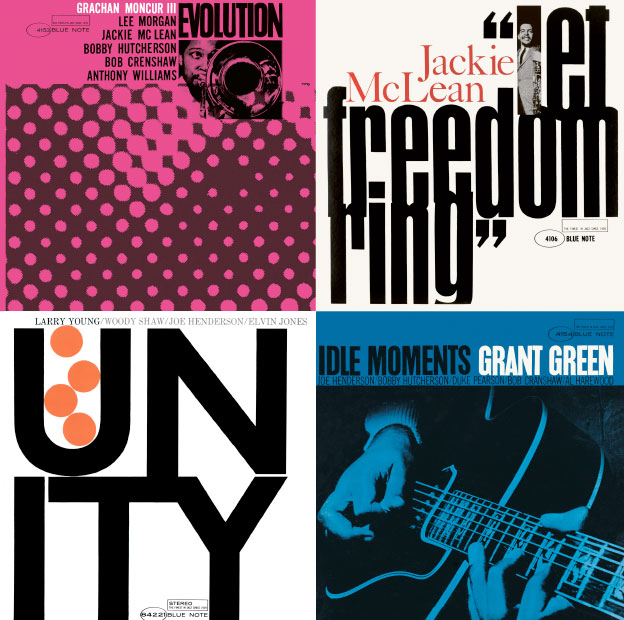

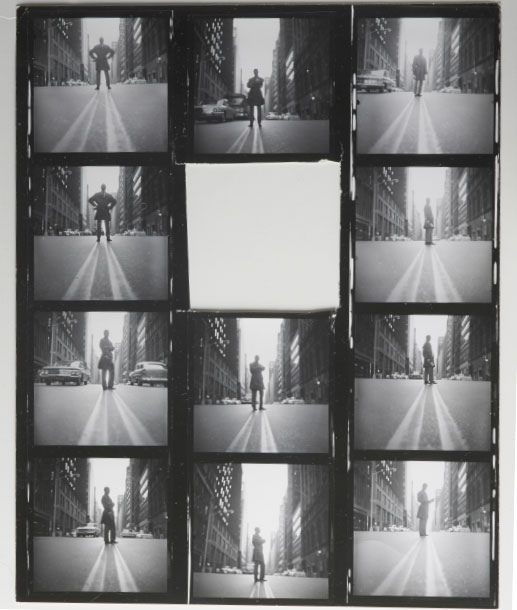

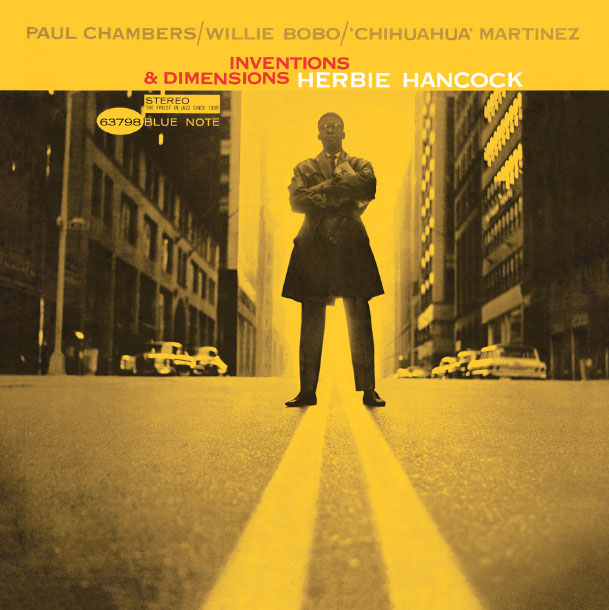

Over the next quarter of a century Blue Note Records not only became the leading jazz record label, but went on to release music by just about every great name in the genre, from Art Blakey and Thelonious Monk to John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins and Jimmy Smith. It also produced some of the most distinctive and beautiful covers in the business, with sleeves that were works of art in themselves. Lion’s boyhood friend Francis Wolff, also Jewish, whom Lion had helped to escape Germany in September 1939, took many of the mostly black and white photographs. The arresting graphics, with their echoes of the Bauhaus, were pioneered by Paul Bacon, who describes his early work as “graphic visions of the music. They were drawn by hand and represented the best I could do at the time with two colors.”

In 1954, Bacon was joined by another young designer, Reid Miles from Esquire magazine. While continuing to use Wolff’s portraiture, Miles placed a heavy emphasis on lettering and graphic marks, using stencils and woodblocks, which he intended to represent something of the rhythm and tone of the music. Ironically, given that Blue Note album sleeves have become the benchmark against which all album designs are measured, Miles was not a jazz fan. But he had a talent for reducing the feel of the music into a simple, modern design that reflected not only the revolution that was taking place in music, but in society. With their spare aesthetic, cropped photographs and glorious colors, even today, they look as fresh and revolutionary as they did then: the epitome of cool. And they were clever, too, reflecting Lion’s belief that jazz was an expressive medium to be taken as seriously as any other high art.

When swamped with work Reid Miles would farm out jobs to friends, including

a young Andy Warhol, then a struggling artist desperate for commissions. Warhol produced four album sleeves, three of which were for guitarist Kenny Burrell. Warhol would go on to create one of the most celebrated pop album covers of all time – the banana on the front of The Velvet Undergound and Nico – but his designs for Blue Note were not on par with those of Miles and Bacon.

The St. Regis New York is proud of its longstanding connection to jazz. Count Basie and Duke Ellington played at its historic rooftop ballroom, and celebrated modern-day exponent Jamie Cullum gave a private acoustic show at its King Cole Bar & Salon in October as part of the Jazz Legends at St. Regis series. Blue Note, too, has endured down the years and moved with the times, under the same guiding principle on which Lion established the company in 1939: allowing musicians the opportunity to make records with “uncompromising expression”. Robert Glasper, Gregory Porter, Derrick Hodge, Ambrose Akinmusire, Wayne Shorter and Jason Moran are just some of the names who record for Blue Note today and they, like just about everyone who has preceded them, make records that are the soundtrack to New York City. Records that define jazz in both their sound and in their look.

Uncompromising Expression: Blue Note: 75 Years of The Finest in Jazz by Richard Havers is published by Thames & Hudson and Chronicle Books; thamesandhudson.com; chroniclebooks.com

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Images: Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images, © 2015 Universal Music Group