Under a high, fierce sun, the Tuareg trader’s face is in shadow beneath his black turban. In one hand he carries a femur-like stick, with the other he leads a roped line of 15 laden dromedaries stretching back across the sand dune. “The source of all life,” he says, “is t-èsm-en… salt. It runs in our people’s blood.”

Since the sixth century, the Tuareg have walked the 500-mile Azalai caravan route from Timbuktu through Taoudenni to the salt mines of Taghaza, packing their beasts with “white gold” to return to the Malian market city. Those caravans were once 10,000 camels strong, and such was its value, the salt they carried was traded weight-for-weight for gold.

Until the mid-20th century, sodium chloride was the most sought-after currency in the Saharan interior, the salt route extending from Mauritania to Ethiopia – where salt slabs were used as coins and the mineral is still traded in bricks – and on to Djibouti. But then, salt runs deep in the veins of all humanity. From Africa to Europe, the Middle East and China, those cubic crystals of sodium chloride were the building blocks of ancient civilizations.

Salt is essential for human life, with sodium playing a vital role in the regulation of many bodily functions, maintaining our fluid balance and enabling the transmission of nerve impulses around the body. But it was this ionic compound’s power to purify and preserve food that was a key catalyst for the progression of Neolithic societies. On the back of salt, whether mined or evaporated from sea or brine waters, cities were founded, religious rituals devised, roads built, gold amassed, old wounds healed in ancient baths, and new lands discovered (after all, Christopher Columbus’s voyage to the Americas was funded by Spanish salt fortunes).

But just as sodium chloride bestowed life and wealth, it also took it away. For the sake of salt, wars were fought, cities and empires destroyed. With handfuls of these white crystals, agreements were made in the Middle East, temple sacrifices consecrated by ancient Hebrews, evil spirits warded off by Buddhists, and sumo rings ritually purified in front of the Emperors of Japan.

The chemical and political potency of salt also imbued it with connotations of spiritual power. In ancient Egypt, natron – a naturally occurring salt found in the soda lakes of the Wadi El Natrun or Natron Valley – was used in mummification and added to castor oil to make Egyptian Blue paint, which adorned tombs, aiding the dead’s safe passage to the afterlife.

Above all, salt was the earth’s natural healer. The Peng-Tzao-Kan-Mu, a 2700 BC Chinese treatise on pharmacology, was partly devoted to the curative powers of salts. While the Greek physician Hippocrates immersed his patients in seawater to treat arthritis and the Ancient Greeks pioneered thalassotherapy, the Romans turned bathing into a grand, ceremonial affair. Herod the Great built his own winter palace at the oasis of Jericho by the Dead Sea in Israel, and floated on waters where Cleopatra had once bathed.

The Dead Sea – in fact a hyper-saline lake – was developed as a spa destination in the 1960s. Today, its chloride-, bromide- and magnesium-rich salt is used worldwide: at The Iridium Spa at The St. Regis Dubai, Al Habtoor Polo Resort & Club, for instance, where it’s mixed with eucalyptus, menthol and lavender oils to hydrate skin; at The St. Regis Cairo, where saltis mixed with an infusion of tomatoes in the foot ritual and with foaming fruit mousse in Glow scrubs; and at The St. Regis Amman, opening this winter, which will be a perfect base from which to take a salt-bathing trip.

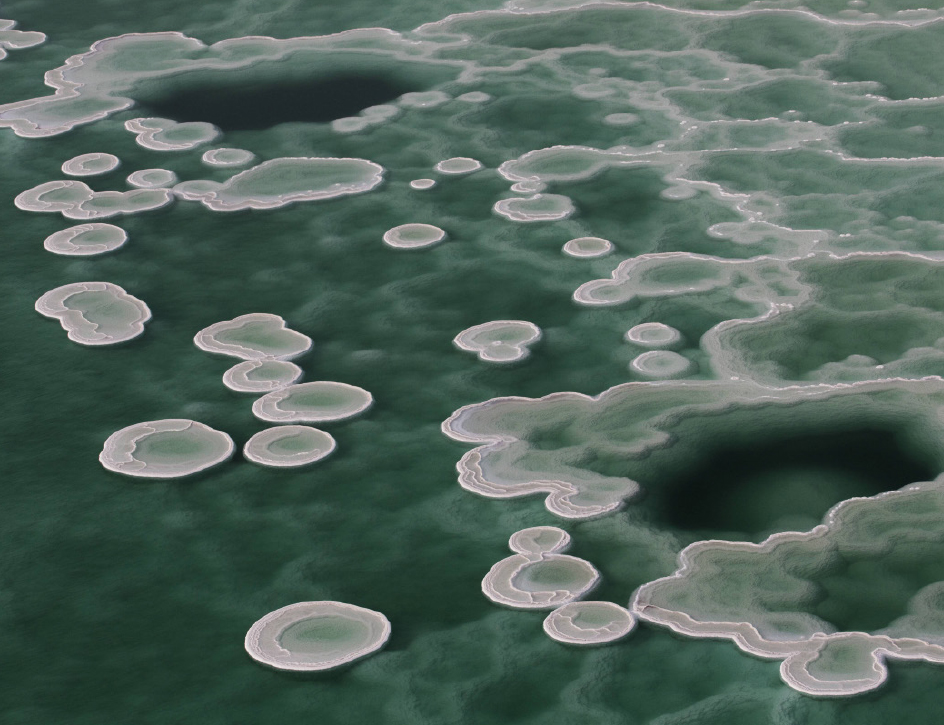

While over-salinity prevented natural life from flourishing in terminal lakes such as the Dead Sea, the Great Salt Lake of Utah and the evaporated salt plains of Salar de Uyuni in the Bolivian Altiplano, these barren landscapes were restorative to the human eye. Their calming effect on the mind and womb-like release from gravity have been replicated by modern flotation-tank therapy. At The St. Regis Punta Mita Resort in Mexico, a 30 per cent concentration of Epsom salts is used to achieve high water buoyancy in the flotation pod. “The deep state of meditation is very close to that achieved in Mexican shaman purification rituals,” says executive spa director Alejandro Ortiz, “while regular skin exposure to Epsom salts improves the mineral content in the bloodstream; magnesium helps to regulate hundreds of enzymatic systems; and sulphates help to flush toxins out of the body.”

Today, with a renewed interest in artisanal salts for their trace-mineral benefits, salt micro-dosing has become an alchemical art-form, with salts delivered in crystals or slabs, smoked or flavored, absorbed or ingested. Fleur du Sel, harvested by hand in France for food, is highly sought-after, with a price tag to match, and Hawaiian salt much prized for a volcanic baked clay component called Alaea, which is rich in iron oxide, and its activated charcoal ions with detoxifying properties. According to Stephanie Kaluahine Reid, from The St. Regis Princeville Resort on Kauai Island, the making of Pa’akai salt, used in Hawaiian ceremonies, is one the islands’ oldest traditions. “It means ‘to solidify the sea’,” she explains, “and Kauai is the only place in the Hawaiian Islands to make salt according to ancient principles.” (Exfoliating vanilla salt polish and Kauai clay are used in Hanalei Bay Ritual at The St. Regis Princeville Resort’s spa and guava wood-smoked sea-salt gives a local twist to an Aloha Bloody Mary afterwards at the bar.)

The newly touted panacea of Himalayan salt comes in pink and black as well. While the latter, also known as kala namak, has a high sulfur content prized in strong foods, the low-sodium Himalayan Pink contains 84 beneficial minerals, much prized by nutritionists. “Slabs are cut from crystallized sea salt beds millions of years old, deep within the Himalayas,” says David Mulin, director of food and beverage of The St. Regis Punta Mita Resort, where the salt is used to line platters of sushi. “The lava is thought to have protected the salt from modern-day pollution, leading to the belief that Himalayan Pink is the purest salt to be found on earth.”

And if you’re looking for colorful ways to ingest trace minerals with your recommended 5mg a day of sodium chloride, here’s another one: sipping a Margarita made by Jorge Carillo, head mixologist at The St. Regis Punta Mita Resort, who encrusts the glasses’ rims with salt ground with chicatana flying ants. This protein-rich delicacy of pre-Columbian Oaxaca adds piquancy: a hint of air, a hint of earth and a strong hit of fire-water.

Your address: The St. Regis Amman; The St. Regis Cairo; The St. Regis Dubai, Al Habtoor Polo Resort & Club; The St. Regis Princeville Resort; The St. Regis Punta Mita Resort

(All photos: ©Getty Images)