In his adopted homeland of Singapore, Tan Swie Hian is not just one of the most famous painters in the country, but one of Southeast Asia’s best-known poets. In 1993 a museum was built to house his masterpieces, and another – covering a square mile of wooded mountain range – is under construction in Qingdao, China. His works are carved into the rock faces of the Three Gorges on the Yangtse River, and painted onto sacred Buddhist sites. As a result, prices for his works have skyrocketed. When his 2013 Portrait of Bada Shanren was auctioned in Beijing last November, it fetched just over $3.3m – quite an achievement for a self-educated painter.

Yet it was for his poetry that the Indonesian-born artist first achieved recognition. Having completed a degree in English literature, he published a collection of poetry in 1968 entitled The Giant – today considered one of the region’s most important works of Modernist verse. His first brush with professional painting came when he took his first and only job, in the press office of the French embassy, where he was encouraged to contribute drawings to a Malaysian literary magazine. When the French ambassador officiated at his first exhibition in 1973, his second career

was launched.

It was at this time, too, that the artist had another awakening – of a spiritual kind. Tan had long been a practising Buddhist, and for a time considered giving up art in order to give himself fully to meditation. Thankfully, he didn’t, and he has subsequently won countless awards, from the Gold Medal at Salon des Artistes Français, Paris (1995) to the Crystal Award from the World Economic Forum (2003). In China, in particular, his work is collected avidly – hence the construction, begun in 2001, of The All-Wisdom Gardens in Qingdao, which is currently about one third complete, and where some 200 stonemasons are engaged in creating huge works of art under Tan’s direction.

What makes Tan different from other artists? What he’s trying to communicate, he says, is “love”. It is evident in whatever he does, whether calligraphy or paintings of trees, mountains, gardens and flowers, which he injects with a spiritual energy. “My aim is to create something that shows how a free mind functions,” he says. “It’s like a hummingbird flying forward, backward and sideways, soaring, swooping or hovering in midair.”

Tan Swie Hian Museum, 460 Sims Avenue, Singapore; tanswiehian.sg

Your address: The St. Regis Singapore

A Smile, 2008

“I made this piece to show how misfortune and happiness walk hand in hand in life,” says Tan. The painting includes a two-line couplet which reads: “The red lava flows, and a hundred flowers bloom. The acid rain pours, and a thousand birds fly”

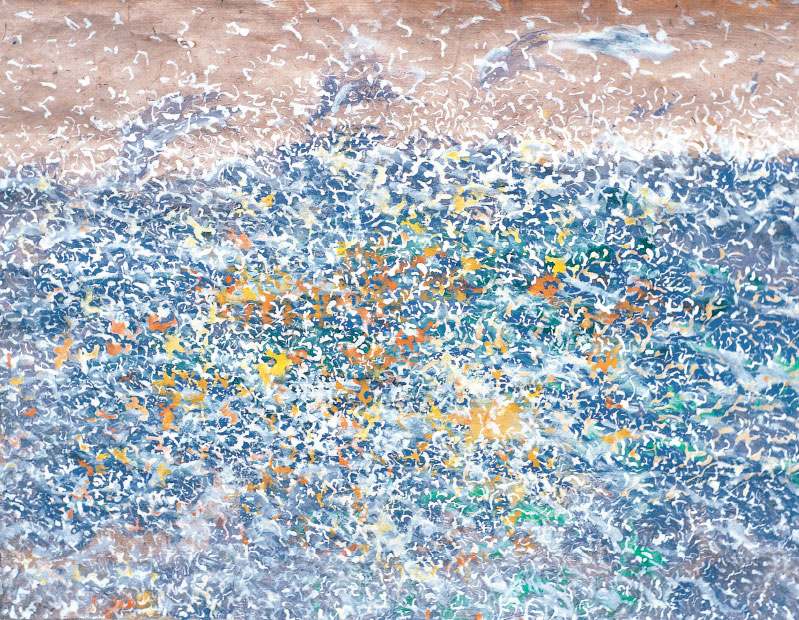

A Sea Change, 1986

Much of Tan’s work also reflects his fascination with the practice of meditation. “One can meditate on the sea until the sea boils, rises to love you and weaves a celestial web of interconnected beings,” he says

A Holy Mountain, 2007

Tan’s devout Buddhism is evident in his continual celebration of the natural world. This painting was inspired by one of his own fables, called A Holy Firefly, about a firefly determined to attract countless other fireflies to a holy mountain. “When night fell, the whole mountain and its heart phosphoresced, visible as well to the shore beyond”