Santa Maria Novella, Florence by Jason Wu

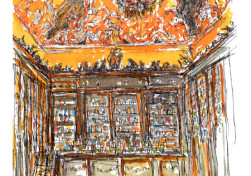

Florence is a great city for walking, which is how I came across the Officina Profuma-Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella (to give it its full Italian name). This exquisite old apothecary celebrated its 400th birthday last year, but has been in existence since 1221, when Dominican friars from the nearby church grew herbs for medicinal purposes. Whenever I walk into this cool, dignified building, I always feel as if I am stepping into a church, with its vaulted ceilings, arched entrances, tiled floors and tall, elegant proportions. It’s like going back in time, with all the bottles, glass-fronted cabinets and neatly attired staff.

What I love most about it – aside from its palatial interiors – are the beautiful scented products. Everything is handmade, from soaps and creams to the famous colognes and fragrances. Lily of the valley, rose, violet, jasmine, honeysuckle and iris are just a few of the scents that fill the air. “The Water of the Queen” was created here for Catherine de’ Medici in the 1500s, a combination of citrus and bergamot, and is still Santa Maria Novella’s signature scent today. The apothecary is presided over by a very elegant Italian gentleman called Eugenio Alphandery, who keeps one foot in the past with his dedication to old-world traditions while keeping his eye on the future of the brand. But everything is organic and made by artisanal methods and I love it that many of the ingredients are grown locally in the hills around Florence. The packaging is really gorgeous, too. Santa Maria Novella is a feast for the senses, its old-fashioned ways a welcome respite from the craziness of the 21st-century world outside its doors.

Your address: The St. Regis Florence

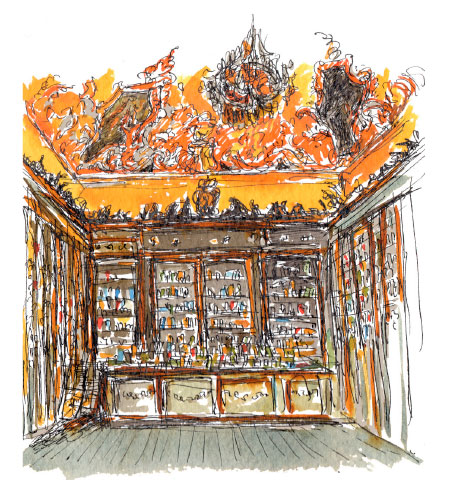

Berry Bros. & Rudd, London by Jancis Robinson

I first discovered this lovely old wood-panelled wine shop in the 1970s, when I started to write about wine. Berry Bros. had been there for a very long time by then. It was founded as a coffee shop at the end of the 17th century, and they still have the scales that were used to weigh the coffee – and the clientele. Lord Byron, William Pitt and the Aga Khan were all weighed here, and regular customers can do the same to this day. The place is an extraordinary slice of history. It has uneven floorboards, high wooden desks (with PCs hidden within), a warren of rooms to the side and wine-filled cellars below. In the 1930s, Charles Walter Berry (the place is still owned and run by Berrys and Rudds) took what was then considered the extraordinarily adventurous step of touring the wine regions of France. Before that, English wine merchants stayed at home and required their vast imports of wine to come to them. These days, the chairman, Simon Berry, has cleverly retained the historic aura of Berry Bros while pioneering all sorts of 21st-century initiatives, such as online retailing and a Hong Kong operation. The historic cellars are now hired out as event spaces and do duty as a wine school. They also hold a lot of tastings, so I’m there at least four times a year. I have many fond memories of meals eaten there, but probably my favourite is of a dinner held in aid of Wine Relief, at which one half of a couple bid £20,000 for a prize lot – without the agreement of the other half! If Berry Bros and Rudd were to close, I’d think that life as we know it had ceased.

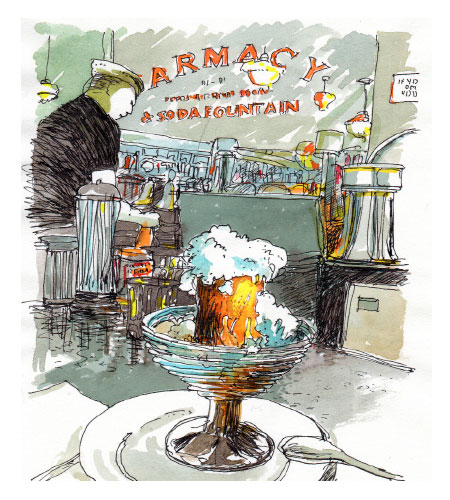

The Brooklyn Farmacy & Soda Fountain, New York by Alain Ducasse

I just adore this place, which locals affectionately call “The Farm”. It was my co-author, Alex Vallis, who first introduced me to the Brooklyn Farmacy & Soda Fountain, and I was touched by the old-fashioned styling, which retains the original pharmaceutical cases and penny-tile floor. And it’s good to know that this delightful Brooklyn enterprise has helped revive interest in the great American soda fountains that existed in big cities and small towns from the late 19th century to the 1960s. Like those wonderful places, this modern-day version offers sweet, homemade soft drinks and the staple – chocolate egg cream. I’ll never forget the first time I tried this dangerously addictive dessert-drink made from chocolate syrup, soda water and cream. The cool, fizzy, chocolate concoction evokes dreams of a mythical golden age in New York. And, trust me, you will always find room for the egg cream. I truly believe that co-owners and siblings Gia Giasullo and Peter Freeman, whose father was a shopkeeper in Greenwich Village for 30 years, have preserved a piece of culinary history. The Farmacy has become part of the fabric – some might say the heart – of this quaint Carroll Gardens neighborhood, and it wouldn’t be the same without it. The shop is lined with shelves of local artisanal foods, helping to sustain and promote the neighborhood – I like that. Every chance I get when I’m in New York, I come to recharge my batteries. It’s about simple pleasures, with a generous helping of nostalgia. Kids from one to 92 will find something in this place; that which is authentic never goes out of style.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Palazzo Spada, Rome by Iwona Blazwick

The combination of the greatest architectural monuments in the world – the Pantheon, the Colosseum, St. Peter’s – fantastic weather, close friends and a burgeoning contemporary art scene make Rome a perennial destination. But I also love its hidden quirks and secrets, and one of my favorite places is Palazzo Spada on Piazza Capo di Ferro. I love the fact that the arcade is both a serious architectural composition and an optical illusion – the Baroque artists were brilliant at playing with perspective. My parents were architects and I almost studied it, so this is a perfect combination of architecture and the art of trompe l’oeil. The artist Cesare Pietroiusti first revealed this marvel to me. It was a cardinal, a mathematician and a sculptor who joined forces in 1632 to create this astonishing optical illusion in the heart of the city. The 16th-century palazzo was bought by Cardinal Spada, who commissioned the starchitect of his day, Francesco Borromini, to add a Baroque flourish. Borromini built a 40-metre colonnade which looks down on to an elegant marble statue. If you look along this beautiful arcade, you will see the spectacle of live cougars leaping across its colonnaded perspective. The shocking truth is, however, that it is only meters long and the statue a miniature 60cm high. The mountain lions are just stray cats made to look hair-raisingly enormous by the false perspective plotted with the help of a mathematician. Add to this the Palazzo Spada Collection, which includes Andrea del Sarto, Brueghel, Caravaggio, Dürer, Rubens and Titian, plus Artemisia Gentileschi, the sole woman artist to gain recognition from the Baroque period – and you have a very special place indeed.