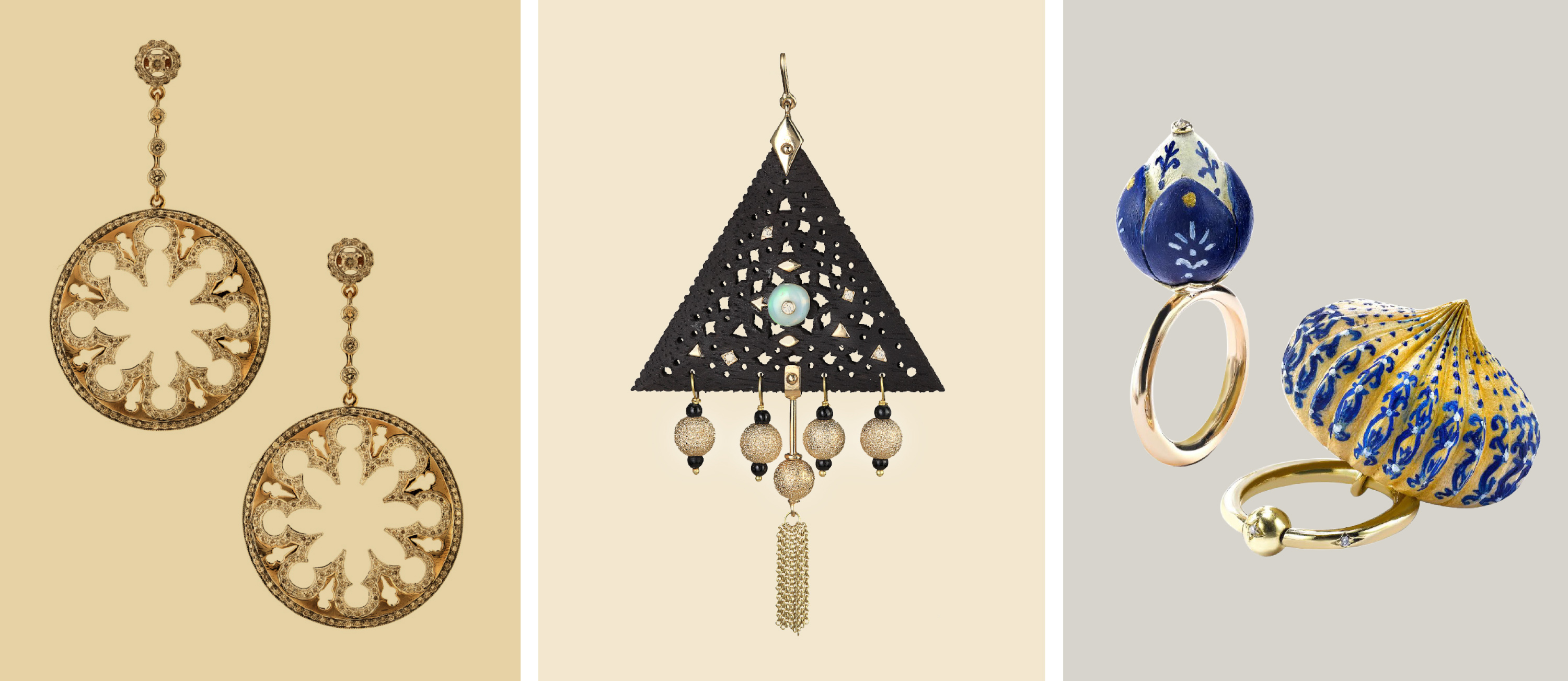

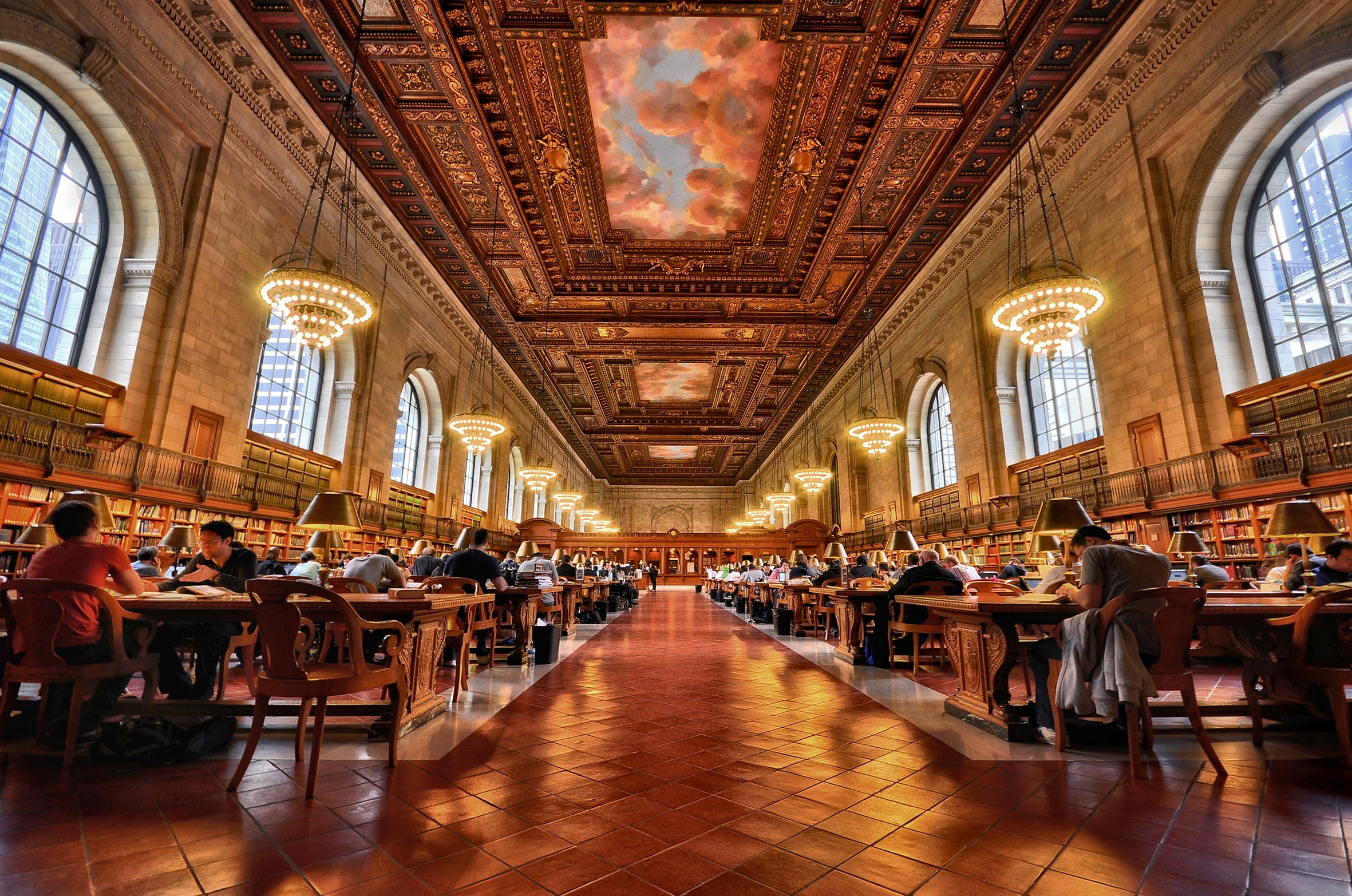

At last year’s Salone del Mobile, the highly influential design fair in Milan, one of the star attractions was an exhibition that showcased Asian design. Walking through a series of coolly chic white rooms, the world’s designerati gazed upon some of the most exciting work coming out of Asia today. However, there were no glossy lacquered pots or bamboo screens, no metal teapots or hand-painted wallpaper. Instead, Chinese designer Naihan Li displayed her striking wardrobe made from rosewood and steel, its angular shape resembling two skyscrapers fused together. Gunjan Gupta from New Delhi presented her Gada Cycle Throne, a beautiful armchair with a seat made from bicycle saddles, the back of a series of rolled-up silk mattresses held in place by leather straps. And hanging sculpturally from the ceiling was the work of Filipino designer Gabriel Lichauco, who took oyster shell and scorched it to make a set of pendant lights that are as unusual as they are lovely.

The exhibition, called alamak!, has big ambitions. At a time when Asia is turning itself into an economic powerhouse, alamak!, which after Venice and Berlin can be seen in New York and LA, aims to be a driving force for innovative modern Asian design. “Alamak! is a southeast Asian expression that means ‘Surprise!’, and that underlines the spirit of the exhibition,” says Yoichi Nakamuta, the Japanese-born, Singapore-based co-curator. “Through the show we hope to change the perception of what design in Asia is, when seen from the West. Its ambition is to be the creative movement from Asia, much like Memphis and post-modernism were creative movements of ’80s Italy, and Droog was of ’90s Holland.”

The exhibition features the work of ten designers from across the region, and while the products are wide-ranging. there’s a common theme: the exploration of traditional craftsmanship. However, it’s no longer just about replicating what has been done for thousands of years, but applying these ideas to create objects that are very much of the 21st century. “Traditions are what have informed the here and now, and have shaped the artists and designers working in these regions. But the designers have given them a new twist,” says Nakamuta. For instance, Jo Nagasaka has taken a traditional Japanese idea of repairing broken porcelain but used 3D printing not only to repair the break, but also to give birth to two vessels from one broken one.

Award-winning Filipino designer Kenneth Cobonpue is not featured in alamak!, but he, too, champions this new thinking. The clientele for his elegantly curving pieces of furniture, made mainly from rattan and palm, includes royalty (Queen Sofia of Spain, Queen Rania of Jordan) and celebrity (Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie bought Cobonpue’s Voyage Bed for their son Maddox). “Today, designers like myself are using modern forms, traditional craftsmanship and natural materials to reshape and change the definition of Asian design,” he says. While Cobonpue made his name with natural materials – Time magazine called him “rattan’s first virtuoso” – he has begun working with carbon fiber and resins, and these modern materials are coming into play across Asia. “The fusion of natural materials and synthetics, and the fusion of the machine-made and the handmade, is the future,” he says. “Natural materials have issues regarding strength and durability, and these issues can be offset with synthetics.”

Coponpue’s change in direction has in part been inspired by his work with some of the West’s most on-trend designers, such as Britain’s Tom Dixon and The Netherlands’ Marcel Wanders. For Wanders, Cobonpue helped produce the Carbon chair, the seat and frame hand-woven using black strands of epoxy-soaked carbon fiber around a mold to create a design that’s both visually and physically light. “When it comes to weaving, we’re second-to-none,” says Coponpue. “We’ve been doing it for a long time, and have experience in weaving almost anything from bamboo to carbon fiber and composite materials.”

Like Coponpue, who studied in New York and worked in Europe before returning to the Philippines, André Fu, one of the region’s most celebrated designers, was born in Hong Kong and schooled in the UK. The pair’s fusion of East and West is another component of contemporary Asian design. Fu’s work is pared back; wood and polished stone are teamed with a palette of quietly rich shades, such as warm gray, green tea and deep purple. “An appreciation of the different cultures remains core to what I do,” he says. “It’s not so much the stylistic adaptation of things that are visually Asian that speaks to my heritage, but of giving a space a sense of balance and calm. Key to this is the sense of relaxed luxury that’s effortless and solid, not superficial and driven by style or a high level of ornateness.”

Fu believes that the surge in hotels in the East – St. Regis will open an additional ten hotels in this part of the world in the next few years – is seeing a commensurate burst of creativity in interior design. “The volume of hotels, combined with increasingly sophisticated global travelers, means designers are doing things differently, experimenting with stronger personalities to create better and more interesting products,” he says.

Bensley, the Bangkok-based design studio behind the landscape architecture of The St. Regis Bali, certainly took an unusual approach, using the famous Japanese-American designer Isamu Noguchi as their inspiration. “We designed 300-plus original pieces of art, many carved from black marble, while some were cast in bronze,” says founder Bill Bensley. “All the sculpture has one underlying DNA that helps keeps unity among the tropical garden ‘rooms’, and that is. ‘What if Isamu Noguchi had lived in Bali in the 1950s? How would things Bali have influenced him?’ Noguchi has a pared-down, Japanese way of creating modern forms – I thought if I used his way of looking at Balinese forms, we might be able to create a fresh body of work.”

Similarly, the penthouse of The St. Regis Bangkok contains a mix of old and new Thai design. Along with a striking glass wall of beautifully colored traditional Benjarong pottery are a number of modern pieces that include a sculpture of stylized lotus leaves by the artist Mongkol, and, on the balcony with stunning city views, a 5ft elephant, painted with Thai letters and numbers and symbols in an abstract pattern by Manop Suwanpinta. “Modern Thai design is coming out of the box,” says Kathy Heinecke – the wife of William Heinecke, CEO of Minor International, which owns the St. Regis Bangkok – who designed the luxe penthouse interior. “It’s embracing its heritage, but also expanding on it with a fresh aspect.” In Thailand, and across Asia, it makes for exciting times.

Your address: The St. Regis Bangkok; The St. Regis Bali

High life

Lights fantastic

Pescador pendant lights, made from oyster shells, by Gabriel Lichauco (above left); detail of an ornament in The St. Regis Bangkok penthouse (above right)

All in the detail

A door handle by André Fu (above left); a Nebbia Interactive wall light, made by nbt.Studio from recycled electronic waste (above right)