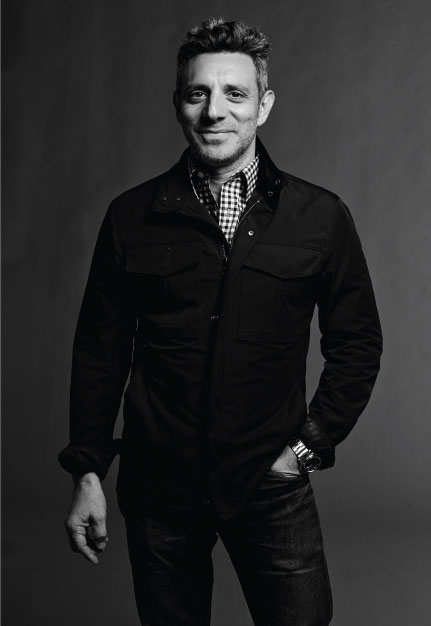

A born-and-bred New Yorker, John DeLucie was a late starter in the culinary world, discovering his calling at the age of 29. Since then, he has become a major figure on New York’s restaurant scene, making his name as the executive chef and partner of the Waverly Inn, the Greenwich Village restaurant that became the ultimate hangout for the city’s glitterati. DeLucie is now proprietor and executive chef of the Lion, Bill’s Food & Drink and Crown, three of Manhattan’s most celebrated restaurants. His latest project has been to reimagine the culinary offering at the refurbished King Cole Bar & Salon at The St. Regis New York.

What’s your earliest food memory?

When I was a child we lived with my grandparents, who were Italian immigrants, and one of my earliest memories is of being in the kitchen with my grandmother. My grandfather sold fruit and vegetables, and he would bring home any produce that didn’t sell that day. It was grandma’s job to make dinner with it. So it could be things like dandelion greens or broccoli rabe – food that was pretty unusual in America at that time. I remember having dinner at a friend’s house in my teens and eating iceberg lettuce. I didn’t even know what that was.

What was the first thing you ever cooked?

Ditalini with tomato and celery leaves and chickpeas – basically pasta fagioli. I’d seen my mother make it a thousand times and one day when I was about 13 I thought, “I want to do that.” I remember painstakingly taking the delicate light-colored leaves from inside the celery, not the big overgrown darker leaves – just like I’d seen my mother do.

Who taught you to cook?

My mother, my aunts and grandmothers were all instrumental. My dad had 11 siblings and my mom had four brothers and sisters, so every Sunday we would gather somewhere with a lot of people. There was always tomato sauce and pasta or ravioli and some kind of meat. It was a very food-oriented family.

What’s your favourite Italian-American dish?

Veal milanese. I just love a pounded veal cutlet drenched in egg and breadcrumbs and pan-fried. It’s the most delicious thing in the world.

What made you become a chef?

I had a lot of different jobs after college. I was a musician. I sold advertising, I represented fashion photographers, I worked as a headhunter in the insurance-brokerage industry. Around the time I was 29 I realized I wanted to cook for a living, so I enrolled on a masterchef class at the New School, and it turned out I had some aptitude. When the course finished I got a job making salads in a very busy restaurant on Third Avenue.

Did you ever have any cooking disasters?

One of my first jobs was at Dean & DeLuca. They asked me to make a potato salad and I got so excited that I forgot one vital ingredient – the potatoes.

How would you describe the menu you’ve created at the King Cole Bar & Salon at The St. Regis New York?

Over the years there have been some amazing chefs at The St. Regis New York, like Gray Kunz, Christian Delouvrier and Alain Ducasse. So when it came to creating the menu, we felt it had to be a real departure from the past. We took a simple approach: super-accessible dishes such as trout wrapped in prosciutto and grilled merguez. We were thinking about the modern traveler who would relish the splendor of the place but not want to get bogged down by food that was too traditional or too complex.

Where’s the best city in the world for food at the moment?

There are so many hotspots – Spain, Italy, the Nordic countries – but Brooklyn is really interesting right now. It’s a very exciting time. Trend-wise, vegetables are pretty hot – dishes such as carrots wellington and parsnip steaks. I think it’s great that we’re paying more attention to stuff that’s growing.

What’s your ultimate comfort food?

A great pizza with a delicious chewy crust – there’s nothing better. I like it best with just tomatoes and chilli and oregano.

What’s the most memorable thing you’ve ever eaten?

I stumbled upon a bakery in Naples with an old pizza oven that had been there for centuries. They were making flatbread, so we bought some, along with some buffalo mozzarella and a bottle of wine, and we sat in the park. It was just glorious – an incredible sensory experience.

If you could fly off right now and eat at any restaurant in the world,

where would it be?

Shiro’s Sushi Restaurant in Tokyo. Simple, fresh, honest – that’s the kind of

food I like.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

The grand British art historian Kenneth Clark, once the director of the National Gallery in London, owned a lot of art. But among Lord Clark’s favorite works was a piece made by Duncan Grant – a precious and much-loved artwork that he stepped on almost every day. Sacrilege? Not at all, because the artwork in question was a rug: designed especially for his eminence by the Bloomsbury Group artist, and frankly, far from the average humble floor covering.

Which goes to show that a rug can be a work of art and usable. There’s certainly a lot to love about a great rug. Like “slow food”, rugs are perhaps the ultimate “slow” art form. They take months and even years to complete, are usually made of natural fibers, last for centuries if kept properly and can be rolled up and transported. They are also warm and tactile.

Which is probably why the artist-designed rug is having a renewed moment in the art and fashion worlds. Pioneering the revival is the Rug Company, which has showrooms across Europe and North America, as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong and the Middle East. It has placed itself firmly in the vanguard of artist and designer-made rugs by commissioning and selling rugs created by such fashion figureheads as Alexander McQueen, Vivienne Westwood and Diane von Furstenberg, as well as a series of one-off tapestries from contemporary artists including Kara Walker, Fred Tomaselli (whom we feature on p.74) and Sir Peter Blake.

“Artists and designers’ contemporary rugs have become really collectable in recent years,” says Christopher Sharp, CEO and co-founder of the Rug Company together with his wife Suzanne. “The nature of their production – they’re knotted and woven entirely by hand by a small group of skilled craftspeople – means that their production is limited, and that demand outstrips what we’re able to produce.” So they’re also an investment, one reason why artists’ rugs are flying off the floors of the Rug Company’s stores, everywhere from San Francisco to Mexico City.

The swell of interest is not limited to New York. Earlier this year the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris hosted Decorum, an exhibition featuring more than 100 rugs and tapestries created by artists ranging from Francis Bacon and Pablo Picasso to Le Corbusier and Louise Bourgeois. This summer in London there’s been an exhibition called Form through Colour, both showing and selling rugs produced by Bauhaus designers Josef and Anni Albers, as well as contemporary British artist Gary Hume.

The organizer of that exhibition, textile and rug-designer Christopher Farr, whose eponymous company has offices in London and Los Angeles, was a frontrunner in the current rug boom. “When we started making artist-designed rugs [in the early 1990s] people laughed at us,” says Matthew Bourne, Farr’s business partner. “Nobody else did it at the time. But we’ve always asked, ‘Why can a sculpture be a work of art and not a rug?’ ” Christopher Farr now sells rugs by a roster of big-name artists and designers that includes Andrée Putman, Jorge Pardo and Sarah Morris.

As Bourne notes, artistic rugs have seen previous high-water marks: “In the 1920s the groundbreaking Myrbor gallery in Paris, led by Marie Cuttoli, sold rugs by Picasso and other artists.” Then, into the 1950s and 1960s, rugs came on to the market bearing designs by artists including Ellsworth Kelly and Alexander Calder. But it took until the 1990s to feel the real heat of revival, which Bourne attributes to “a search for new and durable art forms that are useful as well as beautiful”.

Cast around, and you’ll find plenty more manifestations of the new art rug. Notable in the genre are Michelle Evans’s wool and silk rugs, which have just been exhibited at the J+A Gallery in Dubai; ChiChi Cavalcanti’s graphic, Brazil-influenced rugs, which are prized by architects and interior designers; and Tania Johnson’s meditative rugs based on photographs of natural phenomena such as water. “They take months of painstaking work,” says Johnson, whose clients have included Calvin Klein Home.

There’s even an avant-garde strand in artistic rug-making. In May, at Barneys in New York, an exhibition called Volume #1 showed the results of a limited-edition art-rug project from luxury rug-makers Henzel Studio, which included a Juergen Teller portrait of a nude Vivienne Westwood in rug form, a rug by Helmut Lang, and an astonishing floor-piece by Marilyn Minter called Cracked Glass.

Several of these rugs broke out of the classic rectangular format, and used differing weave heights to create complex images. “This collection was a way to show the rug in a broader context,” says Joakim Andreasson, curator of the project. “The idea was to bring the art rug to a new audience that doesn’t make such a distinction between applied and fine art.” It’s also worth noting that compared to much contemporary art, the rugs were relatively affordable: with prices ranging from $16,000 to $20,000, they are cheap enough, almost, to induce a serious rug habit.

We still have some way to go, however, before precious rugs and tapestries are as appreciated as they were in their heydey, during the Middle Ages. “Tapestry was then judged as a higher art than painting and was more expensive,” says Matthew Bourne. So prestigious was it, adds Christopher Sharp, that “aristocrats would roll up their tapestries and take them to other people’s castles to show them off. Henry VIII had a lot of his wealth wrapped up in them.”

It was probably industrialization that led to rugs, wall-hangings and tapestries being downgraded. “In the 20th century, makers’ skills started to disappear in the West,” says David Weir, director of Edinburgh weavers Dovecot, which itself was revived ten years ago after a period in the doldrums. “Previously we’ve commissioned artists such as David Hockney, Graham Sutherland and Frank Stella, and we’re now returning to the artist-designed rug idea – we’ve recently brought out a series of hand-tufted rugs in collaboration with artist Than Hussein Clark. Weaving translates well to contemporary art.”

Rug-making remains a slow and labor-intensive endeavor, but producers have found plenty of artisans happy to take on the challenge of making art rugs in the developing world. Christopher Sharp uses weavers in Nepal, for example, while Christopher Farr employs Indian craftsmen, and is even making rugs in Afghanistan as part of the US-led AfghanMade initiative.

The one question Matthew Bourne is always asked by buyers is whether they should, like the aforementioned Lord Clark, actually walk on their beautifully designed rugs.

“Well, rugs are made for use, and assuming they’re made well, they are very robust,” he says. “But if people want to put them on the wall, that’s also fine.” It probably depends, as much as anything, from which perspective you like to encounter your art: head on, or from on high.

WHERE TO FIND FINE-ART RUGS

The Rug Company, therugcompany.com; Christopher Farr, christopherfarr.com; Michelle Evans, aykadesign.com; Tania Johnson, taniajohnsondesign.com; Henzel Studio, byhenzel.com; Dovecot Studios, dovecotstudios.com; AfghanMade, afghanmade.com; Top Floor, topfloorrugs.com

Your address: The St. Regis San Francisco; The St. Regis Mexico City

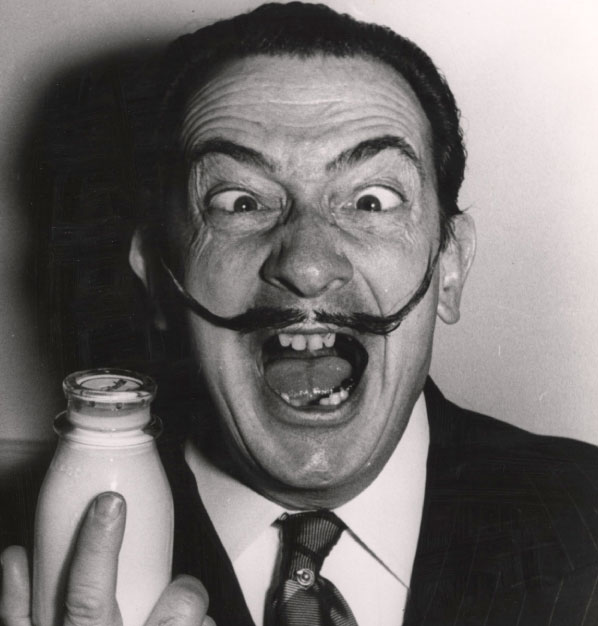

DALÍ… IS… HERE!” For 40 years this gutteral cry announced that the greatest artist of the 20th century, certainly in his own estimation, had arrived in New York at his own private fiefdom, the fabled St. Regis. And whether it was in the hushed acreage of the restaurant, the lofty grandeur of the lobby, the dark enclave of the King Cole Bar or his gilded suite with adjoining studio, Salvador Dalí adored turning this hotel into the stage of his celebrity, his one-man theatre, his private palace and zoo.

Every winter from 1934 Dalí would appear like clockwork, or rather like some distorted cog from his own surreal timepiece, to occupy Room 1610, accompanied not only by his wife and muse Gala, but also a bizarre retinue of associates and animals, including his pet ocelot named Babou. Here he would happily swish around in his golden cape of dead bees or “accidentally” let loose a large box of flies. With arms stretched wide, cane held high, moustaches pointing to the heavens, nobody knew better how to make the grandest entrance. Soon not just fans but also tourists would congregate around the hotel hoping for a sighting of him on the steps of East 55th Street, growling his war cry, each loud sung syllable: “Da-lí… is… he-re!”

No city was better suited than New York to Dalí’s unique brand of showmanship and entrepreneurial hustle, “brand” being the mot juste for this groundbreaking artist who managed to turn himself into a business model and a limited-edition luxury product endorsed by the rich and famous. And no venue suited Dalí better than The St. Regis. (In fact few hotels are as closely associated with one particular artist as The St. Regis and Salvador Dalí.) For New York has as voracious an appetite for culture as for celebrity and commerce, and Dalí was the first to conquer the city by combining all these into one irresistible package: high art and high finance, and every sort of hijinks in between. Dalí’s true celebrity, his serious worldwide fame, was entirely due to the Manhattan media machine. There was an almost symbiotic relationship between the artist and the city’s press, feeding off each other in a mutual frenzy of outrage, a tornado of publicity stoked by Dalí’s pranks and posturings, as if neither could ever get enough of the other.

None of this was an accident, Dalí having plotted it all from the first time he stepped off a boat in New York. He understood that to be a truly modern artist in this one truly modern city he had to become a mainstream star. Which is why, when he arrived in Manhattan before World War II on the steamship Champlain, at the end of an expensive marine expedition from Le Havre subsidised by Picasso, nothing was left to chance. He had even prepared his own publication for the occasion, a broadsheet with the splendid title New York Salutes Me!, which was distributed on the ship and then to the awaiting newsmen when he stepped down the gangplank into New York for the first time ever, on November 14, 1934. Dalí had well and truly arrived.

The mutual attraction between the artist and the media when he stepped off the ship was immediate. In fact, when asked to single out his favorite work of those he had brought on the ship with him, he had one already prepared. Theatrically ripping away the wrappings, he revealed his chosen masterpiece: a portrait of his wife Gala with lamb chops on her shoulders, which made not just the next day’s papers, but that evening’s edition. By the end of his very first day, Dalí was already a hot gossip item.

And so the adulation continued. His debut exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery proved an instant success, and he gave a hugely successful talk at MoMA. Soon, he was being photographed wherever he went. His famous “Bal Onirique” costume ball in honor of his return to Europe, organized by the bohemian Bostonite Caresse Crosby, was so outrageous that the next day there was a maelstrom of publicity, with photographs of his head bandaged in hospital gauze as he danced under a giant cow’s carcass.

Not that the artist stayed away too long. He soon set a pattern of travel, returning every winter, starting in December 1936 with another Julien Levy show that coincided neatly with the MoMA show Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. This was accompanied by the ultimate accolade: a portrait by Man Ray on the cover of Time magazine, which dominated the newsstands and ensured that Dalí would have to sign autographs in the street for as long as he stayed in the city. As Time put it, “Surrealism would never have attracted its present attention in the US were it not for a handsome 32-year-old Catalan.”

Just as successful as his art-pieces were Dalí’s windows for Bonwit Teller department store, where crowds jostled six-deep on 5th Avenue to admire his surrealist woman with a head of roses complete with red lobster telephone. It was in these windows, in 1939, that Dalí staged possibly his most famous New York stunt, climbing into a bathtub in a window and then crashing through the plate glass – with the bath – to thunderous applause.

For Dalí, the best thing about this event was actually to be arrested and to spend time in a real New York prison with real American criminals, before being given a suspended sentence for disorderly conduct. As he admitted, it was “the most magical and effective action” of his entire life.

In spite of this, the artist was soon asked to create one of his most important commissions: his own pavilion at the World’s Fair of 1939, which he called Dream of Venus. In typical style, he came up with an outrageous plan, featuring semi-naked swimmers, and when sponsors objected, he wrote one of the best works of his life, Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness, copies of which were showered over the city by aeroplanes as a full-scale public protest.

There was nothing more he loved than being noticed. As Nicolas Descharnes, the world’s leading Dalí expert, and son of his official personal secretary, Robert Descharnes, explains, “I remember my father recalling a walk with Dalí near The St. Regis Hotel in the 1970s, during which he was dressed in a black coat of panther skin, trying in vain to attract the attention of passersby while gesticulating with his stick. ‘Descharnes, have you seen?’ the artist apparently said. ‘It’s incredible how one can pass unnoticed in this city!’ ”

New York represented absolute energy for Dalí in his annual circuit between Paris, New York and his home in Port Lligat on Spain’s Costa Brava. It’s the city where he dynamized his career, whether during his long residence in America from 1940 to 1948 – when his and Léonide Massine’s ballet Labyrinth was shown at the Metropolitan Opera House, and he had a full retrospective at MoMA – or the winters near the end of his life.

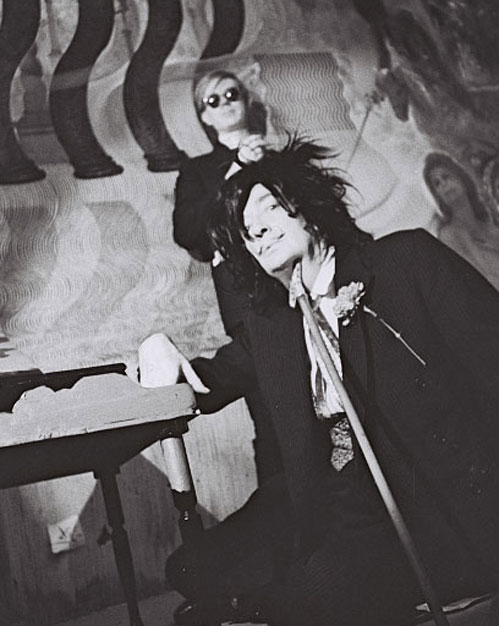

Most of his meetings were in his “résidence d’hiver en St. Regis”, where he’d often hold court looking down on visitors from his 7ft chair, installed on the backs of four turtles. It was here that some of his most important engagements took place, whether that was receiving Helena Rubinstein’s commission to create her frescoes, or meeting for the first time the collectors Eleanor and Reynolds Morse, who went on to create the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. It was in this suite, in 1965, that he first met the young Andy Warhol, that ultimate New York artist. On a subsequent encounter he dressed Warhol up in an Incan headdress before tying him to a spinning wheel and pouring paint all over him.

It was also in 1965 that a remarkable film, Dalí in New York, was made, capturing all the magic and madness of the maestro in residence. Directed by a young Englishman, Jack Bond, the documentary captures Dalí and his circus preparing for his largest exhibition yet, at the Huntington Hartford Gallery. Bond himself stayed in a suite at The St. Regis and in the film we see much of the hotel of the era and Dalí’s “special relationships” with its residents and staff, including the famous waiter Stanley. We also see just how difficult Dalí could be. During one scene, he is filmed demanding 5,000 large black ants (having previously insisted on a sequence of exploding swans, much as at the World’s Fair he had initially conceived a set of exploding giraffes).

As Bond explains, “Dalí always knew exactly what he wanted and he got it. The doormen had to pay Dalí’s taxi fare. He was ‘grand’ in the real meaning of the word. He fitted New York like a glove, it was made for him, and The St. Regis was, and still is, the best hotel in the whole city. He was even able to paint there – he kept a special room as his studio.”

Bond’s film about New York is on permanent show at the Dalí Museum in Florida, a fitting homage to the importance of that one city, and one hotel, in the artist’s life, the place where he turned even his social world into one fantastic happening. As Hank Hine, director of the museum, puts it, “One of our greatest Dalí works is from 1976 and is entitled Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea Which at Twenty Meters Becomes the Portrait of Abraham Lincoln (Homage to Rothko). This masterpiece was painted in the studio that Dalí kept at The St. Regis. The hotel is a living reminder of the vitality of the life of the city and the special vibrancy of great hotels.”

The Dalí Museum is at 1 Dalí Boulevard, St Petersburg, Florida; dali.org

Your address: The St. Regis New York; The St. Regis Bal Harbour Resort

Images by Getty Images, Bradley Smith/Corbis, Bettmann/Corbis, WireImage, David McCabe

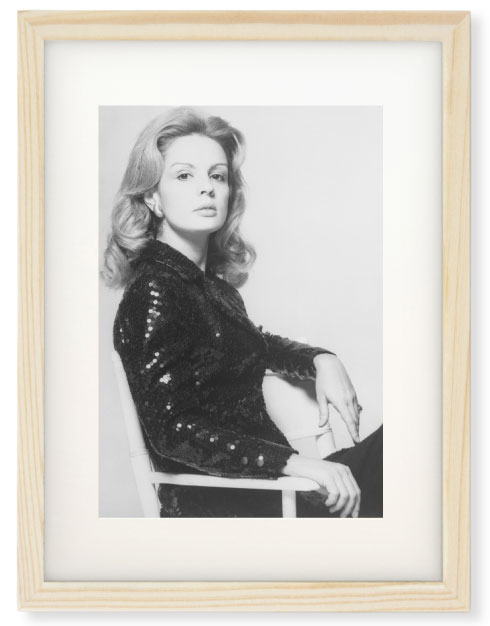

You waited until 1981, when you were 42, before launching your fashion house. Why?

There comes a time in your life when you need to do something new, and that was the right time for me. I’d never done anything before. I asked my friend Diana Vreeland what she thought about me designing some materials and she said, “That’s so boring. Why don’t you design a fashion collection?” She gave me the idea.

What did your husband think of you starting work?

He believed that I should do it, and that was very important for me. You have to have the support of your family, because if you do something they don’t agree with then it’s hell.

Did you ever feel any self-doubt?

Sometimes everything’s fantastic and you think you’re on top of the world; other times it’s more difficult. Fashion, and dealing with the egos in the industry, is a very difficult business.

Were you ambitious?

You have to be ambitious in fashion, otherwise you won’t get anywhere. You have to persevere and realize that you are designing for many different tastes, not just your own. I design things that I wouldn’t wear, but I know they’re going to sell.

You had no formal design training. Did that matter?

No, because in design, the most important thing is to have an eye: for proportion, for mixing colors. You can go to fashion school and learn how to cut a pattern and how to sew, but if you don’t have the vision you won’t know how to put it together. I sketch very badly, but I know exactly what I want. I can’t sew on a button, but I know how it should be sewn on.

Why did you choose to live in New York?

I’ve been in love with New York since I was a child. It’s a very glamorous city, and one of the few cities in the world where there are so many events every night that you always see men looking handsome in black tie and women in evening gowns.

What are the best and worst things about the city?

The best is the weather: when it’s very cold and the sky is blue. The worst is

the traffic.

Apart from New York, which is your favourite city in the world?

Rome. It’s so chic, the Italians are so delicious and the Romans are divine. You can be walking in a small street and suddenly you find something grandiose in front of you, something out of this world. And the Italians are always in a happy mood. They ask you things with a smile, so you can’t refuse. I love London, too, but I don’t like the weather too much.

Where is your favorite place to go on holiday?

Patmos in Greece. We stay with our great friend [interior designer] John Stefanidis, who has a lovely house there. The island is really beautiful, and not so crowded.

How often do you visit Caracas, where you were brought up?

I haven’t been in a long time. I love my country, and I would love to be there all the time, but we became a left-wing country. It’s difficult. Our family house is still there – it was built in 1590 and has always been in the hands of the same family – but we don’t live there any more.

What is the key to looking well-dressed?

Your clothes have to fit properly. You can be in the most beautiful dress in the world, but if it doesn’t fit, it’s a mistake. Sometimes women say, “I want to look sexy”, and for them, sexy is three sizes too small. That’s also a mistake.

You’re a regular on the best-dressed lists. Do such things matter?

It’s very flattering, and it’s very nice of people to say that you are well-dressed, but you cannot think about it all day long.

What is the biggest mistake celebrities make when dressing for the

red carpet?

They wear clothes that don’t fit or don’t suit them. And their shoes are three sizes too big, because they’re on loan.

You have had a long working relationship with Renée Zellweger. How important to a brand is celebrity endorsement?

Renée is great because she doesn’t use a stylist. She comes to me and we discuss what she wants. She knows exactly what she likes, and that’s very rare.

Who in the public eye would you like to wear your clothes? The Duchess of Cambridge, perhaps?

Well, why not? Of course! She has a fantastic figure and she is always properly dressed for her role. I know some people say she’s too serious, but what they don’t realize is that she is representing something.

Is it true that you can get ready for a black-tie ball in ten minutes?

I can get ready for anything in ten minutes. In my mother’s time it was very different, because none of them worked. These women today who take two hours to get dressed – what are they doing after the first 10 or 15 minutes? If I had to spend two hours getting dressed, I’d be so tired by the time I arrived at the party I’d want to go home.

You’re 76. Are you ever tempted to retire?

No, I adore my work. Nobody’s forcing me to do this.

Two of your four daughters work for your company. Does that ever

cause friction?

It’s fun to work with both of them because they have a different approach to what they do and a different eye. They both have a lot of style, but they’re different. Carolina lives in Madrid and is responsible for the perfumes. Patricia lives in New York and is on my design team.

Do they find it difficult to combine working with motherhood?

No. They are very well-organized. To be a working mother

you have to have a lot of discipline and some help.

Did you ever struggle to combine work and home life?

No, never, because I stop talking about work the moment

I leave the office.

Do you burn the midnight oil at the office?

No. If you can’t do what you have to do between 9am and 5pm then there’s either something wrong with you, or something wrong with the organization.

Can women have it all?

Yes. Women are very lucky because we can do many things at the same time.

Men can’t.

You dressed Jackie Onassis in the last decade of her life. Is her style

still current?

Look at photographs of her now: she looks so modern. She was an amazing woman, so cultivated and intelligent, and a great inspiration for me. I have dressed Michelle Obama, too, and she has a different style to Jackie. She mixes it up a lot and wears a lot of young designers. She has created her own style: more informal I suppose. But the world is getting less formal.

What is the most important thing a woman should have in her closet?

A full-length mirror.

Do you find yourself looking backwards now, rather than forwards?

I like the future much more than the past. If you just sit and think about the past, you’re lost.

Have you made any concessions to age in the way you dress?

Of course. Sometimes you see a woman with a fantastic figure in a mini-skirt, and when she turns around she’s ancient. That doesn’t look right to me. You need to be soigné – or at least more soigné than you were when you were 20. The key thing is to dress according to your age, your style and your figure. It doesn’t matter if something’s fashionable or not – if it looks good, wear it.

Does your husband notice what you’re wearing?

Yes and that’s great, because he has a very good eye and he’s not going to lie to me.

You’ve been married for 46 years. What is the secret of a happy marriage?

Love, respect, friendship and a sense of humor. You have to be able to

laugh together.

If you had your time again, what would you change?

I wouldn’t change anything. I would do it all exactly the same way. Even

the mistakes.

When and where were you happiest?

When I had my first child. I loved it. It’s a fantastic experience.

What advice would you give to a fashion designer starting out today?

Love what you’re doing, believe in it, find your own style and like fashion a lot. Nobody knows what fashion is. It’s a mystery.

Images by Conde Nast Archive/Corbis, Christopher Little/Corbis, Alexis Rodrigues-Duarte/Corbis, Bettman/Corbis

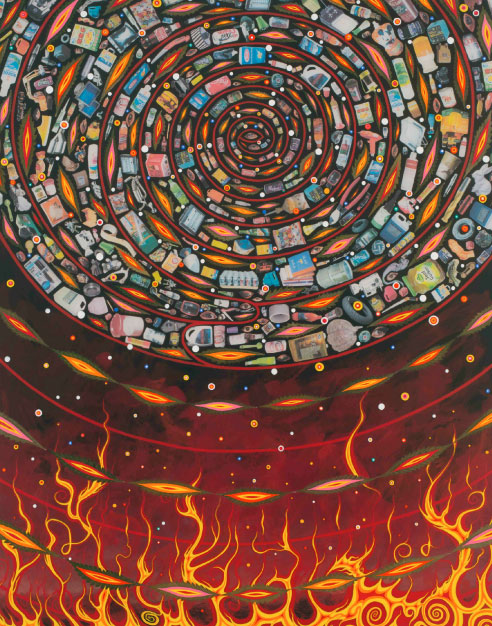

The New York-based Fred Tomaselli is acutely aware that as an artist – particularly one who makes a very comfortable living as such – he is privileged to enter his own little world every time he steps foot inside his Brooklyn studio, even as the world outside seems to be spinning out of control. “The studio is almost like paradise,” the 58-year-old California native says. But he is also a self-described news junkie, reading The New York Times, checking the web and listening to the radio. “The news is constantly penetrating the environment I live in.”

That tension – utopia versus cold, hard reality – pervades Tomaselli’s oeuvre. In his intricately patterned, obsessively assembled – or, as he says, “relentlessly handmade” – “hybrids” of collage and painting, he seems alternately to be inviting the world in and shutting it out. There are elegant, unabashedly beautiful images of birds, but look closer and see that they comprise tiny pictures snipped from magazines; there are fish, trees and flowers fashioned not only from paint but from pills and organic matter like insects and leaves, encased in layers of resin. The New York Times art critic Ken Johnson has compared his hybrids to “windows into the mind of someone in a state of visionary rapture”.

At first glance, his subjects might look placid. On careful inspection, they can veer to the violent: is the bird with its beak thrust into the snake’s mouth in Penetrators (Large), overleaf, feeding the serpent or fighting it? Has the eagle in Avian Flower Serpent just killed the snake wrapped around the tree branch?

Although he lives in Williamsburg, an urban hub of creative types, Tomaselli is actively connected to nature. He is an avid bird-watcher, fly fisherman, surfer and gardener. But his art historical influences also run deep and are as disparate as Japanese Edo prints and Joan Miró’s Constellations series of cosmic-themed paintings, executed at the outbreak of World War II. “I felt like Miró was saying the world is going to hell, but this need for culture continues,” says Tomaselli. “Art needs to be made.”

Tomaselli’s ongoing series, The Times, in which he alters the lead photo on the The New York Times front page, is in the same political vein. He has tweaked images of Ponzi-villain Bernie Madoff, bombed rubble in Syria and children sledding in Central Park. “I decided to become another editor and impose my subjective decisions,” he says. Lawrence Weschler, a well-known cultural critic, has described the series as an “act of witness, a Book of Days across an age of tumultuous transition.”

The series, which has heavily influenced his recent hybrids, will be featured in a solo exhibition at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in October, and in California in February 2015. A selection of his bird paintings will also be on view from October to February as part of The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

His dealers, he says, are adept at insulating him from business affairs. At one time, a while back, uncomfortable with the growing commodification of visual art, Tomaselli tried to stop making it. “But I was really unhappy,” he admits. Now, “I’ve made an uneasy peace with it. Few jobs have no dark night of the soul. I do feel I can do anything I want in the studio. That’s incredible.”

Fred Tomaselli: The Times is at Orange County Museum of Art until May 24, 2015. Fred Tomaselli: The Times, by Lawrence Weschler, is published by Prestel

Your address: The St. Regis Washington, D.C.

Nov. 11, 2010, 2010

In this instalment of his series The Times, Tomaselli

took the original photograph of students protesting

tuition hikes in the UK, or, as the artist says,

“anarchists smashing stuff”, and made an abstraction of brightly

colored shards, like an explosion of stained glass

After Oct. 16, 2010, 2014

Tomaselli’s Times pieces sometimes serve as studies for larger

compositions, such as this one, inspired by a photo

of a machine drilling a tunnel for a Swiss rail system.

“There’s this zooming in and zooming out happening,”

he says of the painting, which pairs Earth’s

flaming core with a kaleidoscope of humdrum man-made products

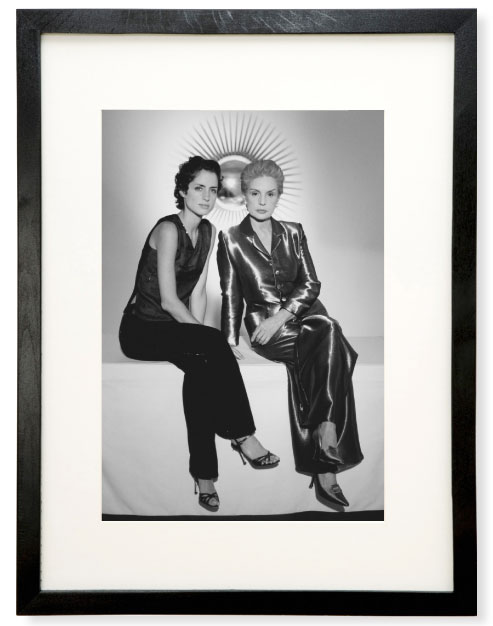

When assessing traits that run through families, physical resemblance, values and attitudes are all up there with things we can expect to inherit from our parents. What is not often high on the list is personal style. One look, however, at some of the world’s most glamorous mother-daughter duos would show you that mothers are in fact as capable of impressing a sense of style on their offspring as they are good manners. Look at elegant women across the globe, and their daughters, and you will find women whose distinctive approach to fashion sings from the same songsheet. Style, it turns out, can be a mother-daughter thing.

In the case of Georgia May Jagger, daughter of Texan supermodel Jerry Hall and Rolling Stone Mick, an approach to style learnt from her parents shines out. Equal parts rock chick and vamp, as likely to be found in Vivienne Westwood as Jerry, she has explained, “My mum has taught me a lot about fashion in terms of what looks good and developing my own sense of style. One thing we both agree upon is that oversized black sunglasses, high heels and red lipstick are the key to dressing up any outfit.” Beyond handy accessorising tips, Hall has also taught her model daughters the power of theatricality in fashion. “I gave them all these films to watch. Actually, they both shot with Karl Lagerfeld, and he was saying to them, ‘OK, be Bette Davis in The Letter.’ And they knew what to do. He said to them, ‘Oh, my God. I never work with girls who know what I’m talking about. Your mother trained you so well!’ ”

If it is indeed possible to be trained in the ways of elegance and style, then surely Charlotte Casiraghi, daughter of Princess Caroline of Monaco and granddaughter of Princess Grace, ought to have had about as good a grounding as one could get. The spitting image of her glamorous mother, 28-year-old Charlotte and Princess Caroline are often photographed side by side, both dressed in Chanel Couture by their friend Karl Lagerfeld. Take one look at the sky-blue Giambattista Valli confection Charlotte wore to dinner celebrating her uncle’s marriage in 2011, the picture of demure yet youthful fashionability, and the maternal influence upon her is impossible to ignore.

Sometimes a mother’s sense of style is so marked, it moves beyond the influential to the fundamental. For the American accessories designer Fiona Kotur, her fashion-illustrator mother provides an endless well of inspiration when it comes to designing her signature evening bags. Describing her mother’s style as “very Coco Chanel with a touch of I Love Lucy”, she cites Sheila Camera Kotur’s brave approach to dressing as one of the most formative elements of her upbringing. “My mother has a strong sense of self and very much believes in individual style and expression. I learnt to value individual character over public opinion, with a bit of irreverence and humor tossed in.” Sheila still illustrates her daughter’s collections each season, encouraging her to push the boundaries of creativity, much as she has been doing since Fiona was at school. “I do remember one outfit she wore, in 1980,” says Fiona. “She arrived at my conservative girls’ school dressed in a completely deconstructed and ripped Comme des Garçons black sack and looked amazing. I was, even then, proud of her lack of self-consciousness.”

Even among the non-fashion set, whose thoughts are set perhaps on loftier matters, the use of fashion as a tool to express values is not lost. Both Hillary and Chelsea Clinton know the power of a well-cut jacket, as demonstrated at countless public occasions over the past decade, not least on the campaign trail. Each also has the confidence to indulge in her femininity without fearing it might damage her ability to be taken seriously. Take the then-Secretary of State, resplendent in fuchsia Oscar de la Renta at the wedding of her daughter, in custom Vera Wang, and you see two formidable women equally willing to indulge in fashion. Likewise, Amal Alamuddin, George Clooney’s fiancée – and more pertinently, an eminent human rights lawyer – and her newspaper-editor mother Baria also display a fun approach to dressing. A glance during the World Islamic Economic Forum at Amal’s mismatched shoes and bright pink Balenciaga coat followed by her mother in a bright purple suit and pearls, and a common appreciation for the colorful is clear.

One family where you would certainly consider exceptional influence to be wielded would be in the Wintour-Schaffer household. Although American Vogue editor Anna Wintour is often quoted as saying that she had wanted her daughter to follow her into fashion, her daughter Bee in fact works in television. However, in ways of style, the apple has fallen rather less far from the tree. Choosing such statement-making designers as Alexander McQueen, Bee is to be found on the Met Ball red carpet each year alongside her Chanel-clad mother in looks that are dramatic yet feminine, tasteful yet push the envelope just enough to be interesting – in other words, pure Wintour.

In families where the resemblance is more literal, you can probably thank location as much as maternal influence in the development of personal style. Hence the look modeled by Kate Hudson and Goldie Hawn, each the poster girl for their particular generation’s take on SoCal chic: the boho approach synonymous with the sort of Malibu-living, Aspen-holidaying, beach-frequenting life both actresses lead.

Head to Brazil, and you’ll find the Dellals, supermodel mother Andrea with her two daughters, accessories designer Charlotte and model Alice, all proponents of a particularly Latin approach to fashion. The trio may now live in London, but you’re as likely to find Andrea and Charlotte in their signature leopard print as you are in a warm winter coat, matching red lips and film-star coiffed hair to boot. Similarly, in the case of the Missonis in Italy, grandmother Rosita, mother Angela and daughter Margherita all display a certain free-spirited approach you would expect from a life lived in Varese, amid the rolling Italian countryside north of Milan where the family business is located and where all three women work. As Margherita explained once, “I grew up in the same place as my mother, seeing the same trees my mother saw when she was at work. The flowers I picked were the flowers that my grandma planted. We have different styles, I wouldn’t make the same clothes that my mom made, or my grandma, but we have the same taste.”

Certainly for Dee Poon, the Hong Kong-based managing director of shirt label Pye and daughter of fashion mogul Dickson Poon, her mother’s influence crossed not only sartorial boundaries but cultural ones, too. With a grandmother who grew up in 1940s Shanghai wearing traditional cheongsam dress, Poon’s mother Marjorie Yang, chairperson of Esquel shirt manufacturers, acts as a bridge between her family’s history in China and their Hong Kong life today. “I remember trips to the fabric stores with my mom and grandma, and the tailor coming to the house to measure and fit cheongsams for them that they would wear out to dinners or to daytime social events.”

Cross over to India, and you will find family duos like dynamic mother-and-daughter Rajshree and Aishwarya Pathy, co-founders of the India Design Forum, whose secret to style also lies in the melding of traditional elements of dress with a much more modern approach. “Mixing traditional with contemporary is something my mother has mastered,” says Aishwarya. “Traditional South Indian jewelry like our family heirlooms are extraordinarily beautiful and well crafted, and pairing them with something contemporary, Western and chic makes for a very eclectic look.” Not that that means her mother sticks to the traditional. “I think it’s fun to combine a pair of ancient gypsy earrings with a trendy blaring yellow cashmere jacket over an AllSaints purple shift, paired with slimming black pants and a busy fur print Dreyfuss sling purse,” says Rajshree. And her daughter? “She would shudder at the very idea!”

It’s not just families from countries with distinct cultural traditions who display tendencies identifiable across national seams, however. Take the French, and you’ll find dynasties whose innate take on something as simple as a pair of jeans marks them out as their own unique tribe. In the case of Jane Birkin (French in spirit, even if English-born) and her daughters Lou Doillon and Charlotte Gainsbourg, a trio of women synonymous with the sort of insouciant, less-is-more sexiness of which Jane herself was the first icon, their singular approach to fashion is so similar it must surely be in their DNA.

Or try the former editor of French Vogue, Carine Roitfeld, and her daughter Julia Restoin Roitfeld, both known for their sexy take on dressing. Carine points out that, while one can have the same fashion sense as one’s daughter, there are important differences to be found in actual wardrobe choices. “I would never share my daughter’s wardrobe,” she has said. “Every five years you have to go through your wardrobe and say, ‘This is possible, this is not possible.’ But you have to be happy with yourself.” As far as she is concerned, the secret to style is a way of dressing that doesn’t overwhelm the personality, an approach to fashion that is all about showing the woman rather than showing off the clothes. “The letter is more important than the envelope. But if you feel good in your envelope, then you will feel better about yourself.”

And therein, perhaps, lies the key to the sort of style mantras that should be passed down through generations. Less about wardrobe choices so much as an attitude to fashion, a mother can instil in her daughter confidence when it comes to the way she dresses. Confidence to make her own choices and to follow her own sartorial rules. Confidence to be her own woman and express her unique point of view. And surely that is something which we would all be glad to inherit.

When we first ordered (on the internet) our Cairn terrier, a diplomat friend of mine asked, “Where will you be sending him to school?” Thinking she was joking, I laughed. Who would have thought, a mere three months later, that Wilson (the aforementioned Cairn, who now travels freely across the Atlantic between London and Long Island) would be attending the most exclusive boarding school in the world?

The Dog House, situated in deepest Wales, not only educates the royal European canine community (who fly their dogs over in private jets from Geneva and Monaco), it also sends weekly updates and progress reports. Wilson came back with a four-page report card (“He excels at swimming” it read, “but is a bit food-centric”), a class photo – and a rather large bill. He also returned with a manicure, pedicure and of course, a blow-dry.

Dogs are the new children. The current generation of twentysomethings has been labeled “Generation Rex” due to the enormous proliferation of dogs in cities such as New York, London, Moscow, Beijing and Paris. The American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently published data that suggests young women are forgoing childbirth in favor of “doggy children”. And while the number of live births per 1,000 women aged 15-29 has plunged by nine per cent, research by the American Pet Products Association shows that the number of small dogs in the US has risen from 34.1 million in 2008 to 40.8 million in 2012. Rich kids like Paris Hilton and Petra Ecclestone (who bought an $83m mansion in LA so her dogs could have more space) might have kickstarted the trend, but today celebrities from Natalie Portman to Rihanna to Marc Jacobs are never seen without a furry accessory.

Dog ownership has grown dramatically around the world, including in China, where panda dogs – actually fluffy chows whose coats are clipped and dyed to make them resemble pandas – are all the rage. “We used to eat dogs,” says Hsin Ch’en, a pet shop owner in Chengdu. “Now we all want one as a companion.” In Japan, where strollers for dogs are as common as leads, some pooches even have their own closets in their owners’ apartments full of changes of outfit – including wetsuits for those heading for the beach. In post-Communist Russia, dog ownership is a sign of affluence: billionaire Andrey Melnichenko’s superyacht has even been specially approved as a quarantine facility, enabling him and wife Aleksandra to take their beloved Maltese, Vala, to foreign shores without having to negotiate the bureaucracy encountered by lesser canines. Brazil is the home of one of the world’s first dog restaurants, Pet Delícia in the Copacabana neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, which even offers a home delivery service.

Dogs have moved from dog houses and kennels to share our most intimate spaces, not only in city apartments, but increasingly also in hotels and offices. “When I first moved to New York you simply didn’t see dogs,” says art consultant Jill Capobiano. “Now you have luxury dog hotels, dog cafés and dog fashion. It’s acceptable to take your dog everywhere, even to dinner parties. When I was growing up dogs were kept outside. Now they sleep, if not in your bed, then in one made especially for them.”

We are no longer dog owners but dog “parents”, now choosing such civilized names for our canine companions as Wilson and Ava rather than Fido or Lassie. “For all the seemingly unbridgeable distance between them and us, dogs have found a shortcut into our minds,” wrote Adam Gopnick in The New Yorker in 2011. “They live within our circle without belonging to it: they speak our language without actually speaking any, and share our concerns without really being able to understand them.”

We treat our dogs exactly like children, if not better, not only investing in interactive feeding bowls to stimulate their brains while they eat, but even going to the trouble of having their intelligence tested by canine cognition experts. Brian Hare, an evolutionary anthropologist from Duke University who studies dogs can even tell you (through one of his nifty personality tests) if your dog is a “socialite”, a “maverick” or a “renaissance dog” (just plain stupid is not a category). In Mr Hare’s book, The Genius of Dogs – co-written with his wife Vanessa Woods – he says, “Natural selection favored the dogs that did a better job of figuring out the intentions of humans”. Of course my dog Wilson knows when I’m grumpy (and moves to another part of the living room). I haven’t tested his IQ yet, but I have sent him on a social skills course.

When my children were small, I often struggled to find babysitters. Today, dogs not only have “dannies” (dog nannies, some of whom even move in to toilet-train) and sleep-away camps, they also enjoy a whole raft of stimulating activities including pet socialization classes, iPad and iPhone lessons (taught at School for the Dogs in New York), doga classes (dog yoga) and dog-walking services that include regularly updated digital maps of the dog’s movements.

Some dog owners can’t be parted that long from their pets. “Let someone else walk Wiley? Never!” says the Manhattan-based former model Bronwyn Quillen. “Wiley [an adopted German shepherd mix] and I go to the park every day for one to two hours. We have a running commentary and Wiley can even spell. When we spell out w-a-l-k he sort of gets excited but when we spell b-e-a-c-h, he goes mad.” Wiley was a shelter dog, which Dog Snobs (or “Dobs”) rate above all others. “There are four categories of dog owner,” says Quillen. “First there are people who buy multi-poos – yorkipoos for example – from pet stores, which are basically mutts. There are those who buy golden retrievers and labradors, which are so overbred they’re not really dogs any more. One rank above that are people who spend money on a good breed. But at the top of the tree are people like me who get a rescue animal.” Wiley knows where he belongs in the family – he is top dog.

“Dogs are simply more reliable than people. I’ve certainly never seen any statistics on dog divorce,” says writer Pamela Redmond Satran, author of Rabid: Are You Crazy About Your Dog or Just Crazy? “I see plenty of helicopter dog-parenting and dogs in snuggly carriers and strollers around Manhattan.” (One pet-owner mentioned in the book spent $15,000 on a specially-made Cartier dog necklace.) Political correctness has of course edged its way into dog life, too. “Can you imagine what would happen if you said, ‘I don’t like my dog?’” she says. “That’s even worse than saying, ‘I don’t like my children’.”

Canine companions also offer endless shopping possibilities. Amy Harlow, a former model and the founder of Wagwear in Manhattan, sees “dogcessories” as the newest fashion growth area. “We’re all design-mad these days,” she says. “When I started my business in 1996 I couldn’t even find a decent lead. Now we think of dog paraphernalia in the same way we think of sunglasses or belts.” Harlow’s bestselling product is the Boat Canvas Carrier ($114), which allows owners to take their dogs with them wherever they want to go. “We’re just as paranoid about dogs now as we are about children,” she adds.

In Paris, jeweler Karin Fainas Martin, founder of Puppy de Paris, creates palatial embroidered dog beds that cost around $15,000, and gold water bowls that will set you back around $12,000. “Why are we all dog mad? In my opinion we are either prolonging family life or delaying childbirth,” she reasons. “Dogs are essentially a continuation of ourselves. In Paris, women think, ‘I am going to walk my dog now. What shall he wear?’”

We know dogs have feelings and dream just like we do. I would go so far as to say they are even artistic. Wilson is not only the inspiration for my own artwork (which he regularly interacts with), but he is welcome in most London galleries. And why shouldn’t he be? As the part-time Cambridge University professor Hardin Tibbs says, “Dogs are intuitive and empathetic, highly attuned to human emotions and feelings. So it is natural for us to ask the question, ‘What does art mean to dogs?’”

When Marco Polo visited Chengdu more than 700 years ago, he found the Chinese city refreshingly reminiscent of his hometown, Venice. “Several large rivers of fresh water come down from distant mountains to flow round the city, and through it. The branch-streams within the city are crossed by stone bridges of great size and beauty,” he observed. “Along the bridges on either side are fine columns of marble that support the roof; for all the bridges are covered with handsome wooden roofs richly decorated and painted in red. All along the bridges on either side are rows of booths devoted to the practice of various forms of trade and craft.”

Today, my first impressions of the capital of Sichuan province are not so different from his. Fresh water still flows through the city, crossed by charming bridges like those painted on willow-patterned china. The Anshun bridge supports a pagoda-roofed restaurant. Tea houses, temples and trees cling to riverbanks amid the silvery skyscrapers of Chengdu’s busy commercial centre. The city is one of the fastest-growing in the world, a magnet for high-tech companies such as Cisco and Dell and abuzz with new construction. Yet one still finds picturesque stalls piled high with bananas or bright yellow sunflowers, stacks of crimson bowls with ivory chopsticks and wicker trays of paper-white mushrooms.

Flying out of foggy Beijing to land at Chengdu is a breath of fresh air. It’s hard to believe that 20 percent of the world’s computers and two thirds of the world’s iPhones are made here. Perhaps its charm lies in the parks, lined with weeping willows, on the Jin river. Or the red-tiled tea houses, the exotic opera, and the food – “as spicy as its women,” as our not-so-politically-correct tour guide would have it. Or the laid-back attitude of the 14 million inhabitants, going about their business with roosters strapped to their backs, gliding through temples in saffron robes, sipping tea under silk parasols all along the riverbanks.

The capital of Sichuan has been a commercial hub ever since the city became a stopover for caravanserai on the silk route. In 1287 AD Marco Polo reported that entrance tolls into the city amounted to 1,000 gold pieces every day. Today, there are no charges. Instead, from the airport, travelers can be whisked to the splendour of Chengdu’s newest attraction, The St. Regis Hotel.

From here, in the capable hands of a chauffeur and an English-speaking guide, exploring the city is easy – and since Chengdu recently became the first city in western China to allow transit travelers a 72-hour visa-free stay, it has become a place from which to explore the country. That might be a daytrip south to Leshan to goggle at the one of the world’s largest Buddhas – or, in my case, a 560-mile journey north into the forested Minshan mountains in the hopes of meeting a panda in the wild.

I had come to Chengdu with a party of international conservationists from the World Wildlife Fund. Our plan was to visit the breeding program for giant pandas at the nursery just outside Chengdu, and then to trek into the nature reserves of northwestern Sichuan, home to the largest number of pandas in the wild.

But before we set off into the countryside, there is a whole city to see: a circuit of temples and tombs, and tea houses serving green tea, woody lapsang souchong and feisty oolong in lidded porcelain cups. At the River Viewing Pavilion Park, we are treated to acrobats bending over backwards (literally) to pour steaming jets of tea into porcelain cups from a teapot with a spout as long as that of a watering can. “Why run the risk of being scalded?” comments a fellow traveler wryly.

Where there is tea, there is also often music. At the aptly named Culture Park, the tea house doubles as an opera house, with ivory walls weathered like mahjong tiles and seats covered in red velvet. The performance that night is an extravaganza of song and dance, acrobatics, fire-eating and magic. Against a backdrop of lavish screens depicting autumnal leaves one moment, spring blossom the next, beautiful dancers with ghostly white faces and colorful brocades pirouette to percussive clanging and tinkling. “Now you see emperor become beggar,” promises our ever-present tour guide, introducing us to the ancient art of bian lian in which identities, even gender, are altered by swapping masks with great sleight of hand.

“Kept inside wide sleeves,” observes our friend, a hawk-eyed wildlife conservationist who carries his binoculars wherever he goes.

In this city, nightlife, too, is fun and colorful. Raised high above the streets, red lanterns and hand-painted signs proclaim the fiery food for which Sichuan is famous. The city’s speciality is the chuan chuan xiang hotpot: bamboo shoot skewers of duck, pork, chicken or fish with vegetables, rolled in spicy oil and dipped into a bubbling broth. Salty, sweet, hot, spicy, sour, sometimes bitter, Sichuan food is never bland. The best local advice I am given is to ask for a menu with an English translation: something I really appreciate when I discover that fu qi fei pian is braised cow’s lungs, and when a fellow traveler discovers that his breakfast, which has the texture of a rubber boot and looks as if it has been dusted with gunpowder, is a thousand-year-old egg.

But then this city is full of surprises. Visiting the Qin Shi Qiao daily market early the next morning, we discover a variety of feet: of ducks, geese, pigs and roosters. Fish and eels wriggle in buckets. Lavender Peking bantams squawk in bamboo cages. Lotus leaves and flowers plucked from lily ponds, chestnuts and bamboo shoots, spices and star anise are piled high in baskets. Just outside, street vendors fan little braziers of hot coals to roast sweetcorn on skewers.

But there’s modernity, too. Beside the temples in which monks in saffron robes pray in a haze of incense and gardens towering with cypresses are the skyscrapers of the commercial district, and enormous shopping centres. On Jinli Street, a recently reconstructed treasure trove of kitsch framed by traditional-style architecture, we stroll amid Mao memorabilia and images of pandas printed on everything, from backpacks and caps to scarves and kites. In this part of the world, the creature is so revered that it is often used as the ultimate political bargaining tool. In 1972, following a visit by Richard Nixon that changed East-West relations for ever, the Chinese government gave two pandas to America which subsequently attracted millions of visitors.

To get our own real-life encounter, we drive six miles on the four-lane highway to the Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, which has had well over 100 successful panda births. The cubs, which are bred using artificial insemination, are raised in incubators and kept in enclosures, more like parks than pens. Booted and gowned like doctors, we visit the nursery where seven hairless, pink panda cubs are curled up in incubators before being moved into the toddlers’ grassy enclosures.

Snoozing on tree stumps, posing for pictures, appearing to beam amiably, the juvenile bears are delightful. Although they have toys and wooden climbing frames to play with in their enclosures, the creatures’ main activity is feeding. Adults eat about 45lbs of bamboo every day, spend 16 hours a day chewing it, and the rest of their time asleep. Pandas won’t consider bamboo shoots more than a day old, so truckloads of the stuff from the mountainous north supplement the harvest from groves at the Research Base.

Sadly, efforts to reintroduce them to the wild have not been successful. A national survey from 2004 estimated there to be only about 1,600 pandas in the wild, 80 percent of which are in the 38 forest reserves in Sichuan Province. One such, the Wanglang Nature Reserve, is where we hope to encounter one.

Our journey begins on the flat, driving through farmlands outside Chengdu. Around rickety little white-walled houses are clotheslines and gardens dotted with duck ponds and fruit trees. Watermelons hang from vines, and the pepper plants that give Sichuan cuisine its kick can be seen clambering over walls. The area is intensively farmed and densely populated.

We travel on Highway 101, passing lorries loaded with squealing pigs, a cyclist with roosters in a bamboo cage weaving past buses, and stretch limos with smoked-glass windows. As the landscape of the Sichuan basin turns golden with wheat, traffic slows for combine harvesters to move sluggishly across it.

The rolling farmlands give way to mist-shrouded forest and mountains that rise 10,000 feet to the Tibetan Plateau. As the road narrows and begins to climb through steep, forested gorges, the color changes from grain to green, with pine, rhododendron and barberry hugging the slopes. As it winds around steep mountainside, the road sometimes slips away or is covered by landslides. Erosion is so bad that travel is only permitted in daylight. Along riverbeds, flat-bottomed boats trawl for stone and sand to rebuild the road, the boatmen reduced to the size of ants as we climb.

As dusk falls we stop at the small town of Tudiling. Yaks graze in the grassland and our hotel is surrounded by a cluster of little stalls lit by single lightbulbs selling Tibetan dolls, rice-paper drawings, Mao Zedong caps, incense and the carved stones and ammonite fossils, known as saligrams, that every Buddhist mountain traveler holds sacred.

Heading west for the hills of Wanglang early the following day, our route takes us past roadside beehives and clusters of beautifully scented white trumpet flowers growing in the rocky shale. Long ago a traveler brought juniper here, and there are juniper berries and peppercorns and honey for sale at roadside stalls. We stop at one where groomed yaks, snowy white, have red pom-poms stuck on their blackened horns. Stallholders invite us to pay to pose for pictures with their beasts, wearing red cowboy hats. In the thin, crisp air our breath steams even at midday. We eat rice and drink green tea from small bowls.

As gears grind round hairpin bends and our teeth chatter as we cross precipices, there isn’t one of us who wishes we had taken the easy route to the nature reserve by flying to Jiuhuang airport to reach our next stop, the bustling tourist resort of Jiuzhaigou. “Just ten years ago this was a village with 2,000 residents,” our WWF field officer tells us. “Today about 20,000 tourists a day head to Jiuzhaigou.” Mass tourism is as much a threat to panda habitat as the logging which the state has now prohibited in the region.

Driving down into the Jiuzhaigou Valley, a necklace of hotels and casinos and flashing neon signs appears in the middle of nowhere. A plastic palm tree stands forlornly beneath a street lamp. It’s not pretty.

Just outside the town, however, lies the spectacular Jiuzhaigou Nature Reserve, studded with turquoise lakes, fast-flowing waterfalls, forest trails and snowy peaks rising to 14,800 feet above sea level. Unesco has declared it a world heritage site. It is a paradise for birdwatchers and botanists. The water is so clear that when I drop a seed into a deep pool in the lush marshlands, I can watch it sink gently all the way to the bottom. High levels of calcium carbonate in the water turn the area’s lakes the most remarkable shades of jade and turquoise, giving rise to such poetic names as Promising Bright Bay, Five-Colored Pool, Pearl Shoal Waterfall – even Panda Lake.

While it’s a beautiful stop-off, we have another three and a half hours to travel on a hazardous road to Pingwu and from there, a further 75 miles to Wanglang Nature Reserve on a road pitted with craters. Sheer cliffs rise above us on our climb. We stop to photograph the only other vehicle on the road, a tractor carrying a family dressed formally in silk robes as if on their way to a wedding ceremony.

Just as the sun is slipping behind the towering mountains, we reach the Wanglang Nature Reserve, where the WWF has helped to establish an eco-lodge complete with learning center and a veranda from which to admire the spectacular view. At 9,800 feet, though, it’s not just the views that take your breath away. It’s the thin mountain air.

After a comfortable night’s sleep, we are ready to explore. Outside the lodge, a wooden sign painted in Chinese and English explains what awaits those who can make it: “Baisha valley is formed by the rockslide. Walk along this way you can see grand mountains covered with snow, cuckoo and trees buried by mud flow. Single seed Savin and spruce are the main trees in this stretch of forest. There are lots of orchids under single seed Savin. Every year the best time to view and admire the orchids is from May to August.”

We begin in the petrified forest, where strangely sculptural, silvery black and white fossilized trees are surrounded by spruce, fir and Alpine cypress. Here wild roses bloom, pale pink and yellow, and the sudden, sharp lemon tang of azaleas reminds me that China is one of the world’s great sources of plants that have now spread across the world. This ancient forest contains species I have only ever encountered before in London’s Kew Gardens: the Venus flytrap, rare fritillaries, vivid orchids, and the curious Chinese sumac, a much-prized ingredient in Chinese medicine. All are vulnerable to plant hunters, and so anti-poaching teams regularly patrol the reserve’s perimeter. They are also charged with protecting the native fauna, which includes musk oxen and golden snub-nosed monkeys, as well as the elusive panda. We hold little hope of seeing one of the latter, though, when the park’s director, Jiang Shiwei, warns us that he has never seen a panda in the wild, and he’s lived here for seven years.

As we climb, the going gets tougher. Suspension bridges with a lattice of saplings span torrents. Tangled undergrowth lashes us and bamboo saplings whip across our path. It’s cold, too. The watery sun at this high altitude never penetrates the dense forest. Suddenly a shout goes up from one of the park patrollers. He has found panda droppings. “How old is it?” “Six or seven months.” “So it’s only a panda cub, then?” “No, the feces is six months old.”

Not exactly hot on the trail of a panda, we decide to call it a day and return to the lodge to prepare for the long ride back to Chengdu.

While disappointed, I remind myself that Peter Matthiessen wrote his bestseller The Snow Leopard without spotting a single one of the beasts on his trek across the high Himalayas. And we do know that they are out there. On YouTube there is footage captured last year of an impatient giant panda hustling her dawdling cub on a high mountain pass in Anzihe Nature Reserve, about 65 miles from Chengdu.

Even though we haven’t managed to find this elusive creature, the magnificence of the landscape that these solitary creatures inhabit, with its fast-flowing rivers, precipitous gorges and blue mountains wreathed in mist, more than compensates. The Tang dynasty poet Li Bai, who lived during the 8th century, described the journey to Sichuan as being more difficult than the road to heaven. Back in Chengdu, and about to fly halfway back across the world, I reflect that it was worth making that hazardous journey. For it was here that we discovered a real Shangri-La.

Your address: The St. Regis Chengdu