One of the world’s greatest living painters, Sir Howard Hodgkin, is sitting in his wheelchair in his vast London studio. “Forgive me if I don’t get up,” he says. At 83 years old he can be forgiven for needing a little help to get around these days, yet his compulsion to paint and to travel the world remains indefatigable. In the first three months of this year he painted six new works in Mumbai, the city he first visited in 1964 and which he calls home for several months of the year. Since his return to London he has continued with his painting, standing painfully at an easel, for a major new show of works at the Gagosian Gallery in New York in 2016.

India has been a recurring theme in Hodgkin’s work throughout his life. The most recent exhibition of his works, at the Gagosian Gallery in London, was of his Indian Waves series, created in 1990 and 1991 and rediscovered last year in an attic. Each of the 30 works was painted on handmade Indian khadi paper, a fluid wave of ultramarine at the bottom of each sheet representing water, an emerald arch above representing hills, and vivid impressions painted over the top reflecting places and events in India.

The colors he uses capture the light and vibrancy of the country in big bold strokes. In Mumbai Wedding, joyful explosions of crimson, orange and yellow implode like fireworks in the sky. In Storm in Goa yellow lightning flashes over an electric green sky with a sultry, inky dark sea surging below. At the time he painted the series, Hodgkin admits he wasn’t sure about it, but today he confesses to being pleasantly surprised – a reaction which his patrons clearly felt, too; each of the paintings sold on the opening night for $90,000.

Although knighted in 1992, the London-born painter – who was evacuated aged eight during the Second World War to Long Island, represented Britain at the Venice Biennal in 1984 and has exhibited in leading museums including the San Diego Museum of Art and the Metropolitan in New York – never uses the title ‘Sir’. “It’s not relevant,” he quips, “unless it’s to try to get an upgrade on an airplane.”

But then, not much about Hodgkin could be described as straightforward. He doesn’t like to talk about his paintings, insisting, “It’s not the way I work.” And he particularly dislikes the label “abstract artist”, preferring to use the term “representational painter”.

While there are clues in their titles as to what each painting might represent, knowing that gets the viewer only so far. Hodgkin’s paintings are not true to life, being rather pictorial equivalents of their subjects, or what the director of London’s Tate Modern, Sir Nicholas Serota, describes as artworks that capture “both the tangible and intangible sensations that we retain from a fleeting experience”.

Hodgkin’s visual recollection is so strong that he rarely uses sketchbooks, painting instead from memory. Describing a trip he made with his partner, Antony Peattie, in 2014 to a Sufi music festival in Rajasthan, hosted by the Maharajah of Jodhpur, Hodgkin recalls “breakfasting on the hotel terrace, a flautist improvising and posing with a peacock, dour Uzbekistani musicians the picture of grimness and, in the distance, a white marble bench”. There you have the scene, better than Instagram because you can read into his word picture what you see in your mind’s eye: a reminder that his paintings are not snapshots.

New York’s Gagosian Gallery will display a selection of Howard Hodgkin’s latest works between March 4 and April 30, 2016.

Your address: The St. Regis New York; The St. Regis Mumbai

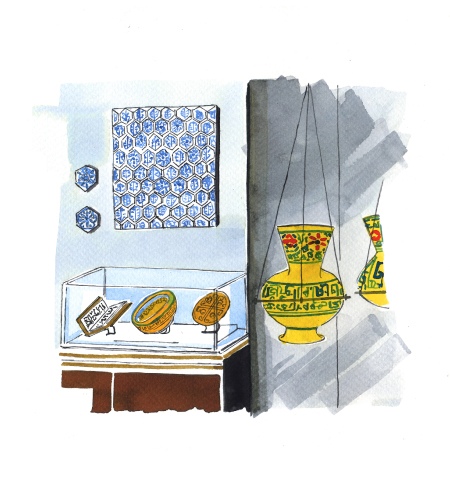

Images by: All artworks © Howard Hodgkin. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, except ‘Tea Party in America’. Portrait by Robin Friend; © Howard Hodgkin. Image courtesy Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Flying colors

Howard Hodgkin in front of his painting Border, 1990-91. Left: Hello, 2004-2008. As in so many of Hodgkin’s paintings, the brushstrokes spill over on to the frame, suggesting an exuberance without boundaries. Although this small work measures just 11½ inches x 13½ inches, it dominated the walls of the gallery in which it was first shown.

Tea Party in America, 1948

Hodgkin was just 16 years old when he painted this tea party on his first return visit to Long Island, where he had lived for three years during the Second World War with his mother and sister. Using a sable brush, he experimented with different techniques. The hand holding a jug is executed in a wash, the grey and white striped tablecloth appears combed, and white spotted beads on blouses and on wrists evoke pearls and diamonds. Enormous hands in the foreground place the painter (and spectator) at the head of the table, as a participant in the tea party, while the background recedes in a swirl of white and grey with mauve.

© Howard Hodgkin. Image courtesy Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

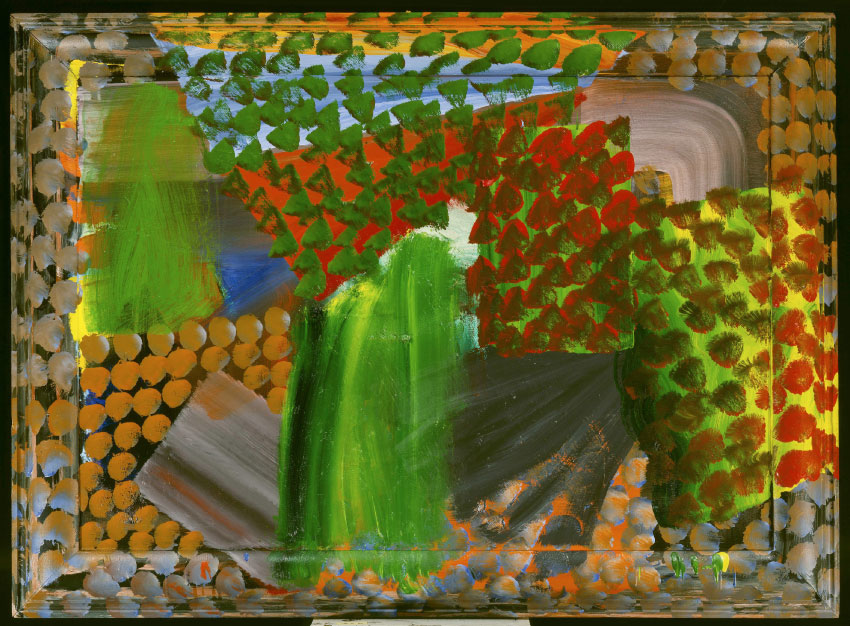

Where Seldom Is Heard a Discouraging Word, 2007-2008

One of 20 works completed in 2007 and 2008 when Hodgkin explored themes of American freedom and erotic intimacy – “the facts of life as visual art”, as the art historian Robert Rosenblum once described them – this boldly vibrant landscape is one of the largest in the series, measuring 80 1/8 inches x 105 inches. Three horizontal fields are dominated by a polka-dotted sky with a single, smudged cloud on the horizon above a sunny yellow wave anchored upon a burnt orange ground. The viewer is drawn into a landscape that reaches out beyond the physical limits of the painting, surging with optimism for the future.

Letters from Bombay, 2014-2015

For more than 50 years Hodgkin has been inspired by India, its landscapes and its people. Even India’s monsoons sweep through his visceral canvases. Every year he escapes the British winter to spend three months in Mumbai with his partner, Antony Peattie. “I am a representational painter but not a painter of appearances,” Hodgkin explains. “I paint representational pictures of emotional situations.” Thus the viewer can be led by this missive from Bombay in whichever emotional direction it takes him or her. Emphatic dark brushstrokes, like slashes, rupture the painting; a crimson fringe surrounds the blue bay, while a golden sunrise offers new horizons.

Old Money, 1987-1989

Old Money appears to be a comment on the tyranny of money in the consumer society of the late Eighties: awash with coins, a lottery of numbers and expectations, fruit machines and even an ATM, it features a hand reaching out among the green wads of notes. In conversation with Antony Peattie, Howard Hodgkin says that nobody seems able to respond to art “without a gush of words… I am happy for people to talk about my pictures but I wish devoutly that I wasn’t expected to talk about them myself. The more an artist talks about his work, the more his words become attached to it. I want people to look at my pictures as pictures, as things.”