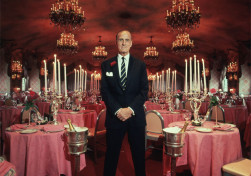

“Picasso was the greatest artist in the first half of the 20th century, Andy Warhol in the second.” That’s the typically blunt opinion of Peter Brant, billionaire industrialist, entrepreneur and art collector, and his money has followed his mouth. Brant, 66, won’t specify how many Warhols he owns, but it’s in the hundreds, and he has thousands of other contemporary American artworks, by Jeff Koons, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Richard Prince… In a land of art collectors, he’s one of the best connected and grandest.

Brant, whose fortune derives from newsprint, lives in Greenwich, Connecticut, with his second wife, the former supermodel Stephanie Seymour. In 2009 he started The Brant Foundation to share his inventory, and this year he showed 130 Warhols – the result of a collecting career that began in 1967. “I was about 19 when I first bought a Warhol Soup Can drawing,” he says impassively, pointing out that he was following in parental footsteps. “My father [Murray Brant] collected classical paintings and Old Masters.” Another life-changing moment came on the slopes of St. Moritz. “As a teenager I met the art dealer Bruno Bischofberger while skiing,” Brant says. “He introduced me to [Warhol’s dealer] Leo Castelli.” Hooked, Brant then met Warhol in 1968, “just after he’d been shot”, and became a friend of the artist. “Although Andy was avant-garde, he was never interested in drugs or the self-destructive. He was a voyeur, interested in people.” Brant even produced a couple of Warhol films in the Seventies, L’Amour and Bad, and was surprised to find out how famous the artist was in Europe. So he kept buying Warhols, with the odd hiatus when he attended to horseracing and polo, and has remained true to his friend. While some reckon that his celebrity paintings squandered talent, Brant refutes this.

“I like all Andy’s work, particularly his pictures from the early Sixties,” he says. He’s proud of Licorice Marilyn (1962) and Shot Blue Marilyn (1964), both on show at the Foundation. Brant, who now owns Interview, the magazine Warhol founded, also learnt the art of acquisition from Warhol. “Andy was the quintessential collector,” he says. “We shared a taste in antique furniture and went on buying trips to Paris.” Warhol snapped up everything, from Art-Deco chairs to cookie jars. Contemporary art has enjoyed a bull market recently. Is it over? “On the contrary, I think it’s a better time than ever,” Brant says. “People say ‘You were lucky to live through those times.’ But art has never been more

appreciated than now.” So look around, he exhorts. Find the new Andy.

The Brant Foundation Art Study Center, 941 North Street, Greenwich, Connecticut; brantfoundation.org. By appointment