Canadian Jennifer Gaudet, founder of Jennifer’s Hamam in Istanbul’s Arasta Bazaar, is a passionate defender of Turkey’s vanishing textiles tradition. Thankfully her mission has been boosted by the global popularity of the hamam towel or pestemal – a compact and lightweight towel that’s highly absorbent and dries five times quicker than regular towels. “The hamam towel is something very special in Turkish culture,” she says, “because the hamam is very special. It wasn’t just a bathhouse, it was a communal meeting place. Visiting the hamam was a daily ritual. Over the centuries, Turkish women took this functional item – the towel – and transformed it into a thing of beauty.” Istanbul now boasts hundreds of stores selling a vast array of towels. And with pastels gracing catwalks this season, pestemals like those pictured (from Ailera) are sure to go down a storm. Best of all, when you’re not on holiday, they have a variety of other uses. “People use them as tablecloths, throws, curtains, scarves or shawls,” says Gaudet. “The only limit is the owner’s inspiration and imagination.” jennifershamam.com; ailera.com

Demand for globes has rocketed in the past decade. Yet for the most part, today’s globes are a far cry from exquisitely made antique versions, which are expensive and often too delicate for everyday display. A hand-painted Bellerby & Co. globe, like the exquisite “Livingstone” model pictured, takes a vast amount of expertise to complete, as the firm’s founder Peter Bellerby discovered when he decided to make a globe for his father’s 80th birthday. “I thought it would take three or four months” he recalls. “After all, how difficult can it be to make a ball and put a map on it?” Bellerby soon discovered the challenges facing anyone set on creating a high quality globe. Indeed, even sourcing a genuinely round sphere proved nigh impossible. Six years on, however, his bespoke globe-making firm in London now has orders arriving from all over the world. So, in Bellerby’s opinion, what is it about these objects that elicits such passion? “There are so many things a globe evokes, from childhood geography lessons to a sense of adventure… to wondering why you’re on the planet.” bellerbyandco.com

When it comes to haute joaillerie, green is the color. Angelina Jolie, Cate Blanchett and Mila Kunis have all been spotted wearing emeralds on the red carpet; the famous Colombian emerald mine Muzo is creating a precious stone brand with top designers like Shaun Leane and Solange Azagury-Partridge; and earlier this year in Hong Kong, Christie’s sold an emerald ring from Afghanistan for $2,276,408 – an auction world record. While Colombian emeralds remain the most sought-after, African stones are coming to the fore, according to Keith Penton, Head of Jewelry for Christie’s: “African emeralds are being used by many of the best jewelry houses in their current designs. I’m sure that in time the best African emeralds will create record prices.” If you’re thinking of investing in emeralds, Penton offers the following advice: “Look for the best clarity and the richest color and avoid opaque or overly pale colored stones with no appearance of life. Above all else, buy something that you love and that you’ll wear. There’s something very sad about jewelry that lives in a bank vault.” christies.com

Ever since Claude Monet was made artist-in-residence at London’s Savoy hotel in 1899, painting a series of iconic views of the River Thames from his top-floor room, hotels and art have enjoyed a fruitful relationship. St. Regis in particular has a glorious tradition of working closely with artists, notably in the murals that adorn the walls of each St. Regis hotel bar. This custom dates back to 1932, when Maxfield Parrish’s celebrated Old King Cole was installed at The St. Regis New York, depicting – legend has it – the hotel’s founder, John Jacob Astor IV. Today, all St. Regis hotels and resorts feature eye-catching works, often by local artists, ranging from Andrew Morrow’s Love and War at The St. Regis San Francisco to Bedri Baykam’s Bosphorus Breeze at The St. Regis Istanbul.

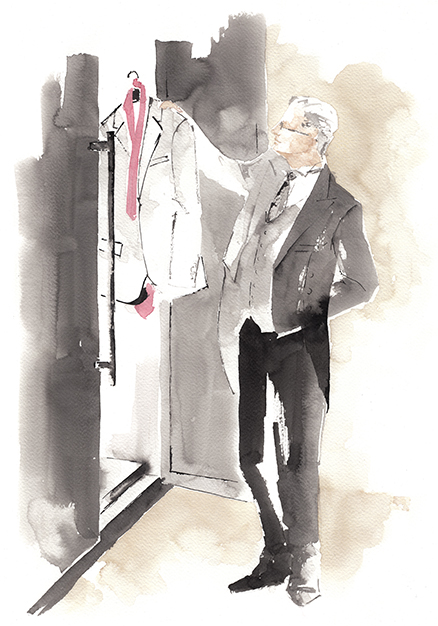

Now St. Regis has teamed up with fashion and lifestyle illustrator Maya Beus, whose sketches and watercolors have previously been commissioned by the likes of Vogue and Oscar de la Renta, on a three-month project exploring the role of the butler. For Beus, who is based near Split in Croatia, the project, entitled Butler Stories, involved intense three-day drawing assignments at three St. Regis hotels – Florence, Rome and Istanbul – meeting the staff, getting a feel for each property and doing quick-fire sketches that she later transformed into delicate watercolors.

“Normally I work from photographs so it was a new experience for me to sit in a hotel lobby or a bar trying to capture a moment and tell a story,” says Beus, who featured among the world’s leading up-and-coming illustrators in Taschen’s publication, Illustration Now! Fashion.

A butler lays the table of the exquisite Royal Suite

of The St. Regis Rome beneath a Murano chandelier

The St. Regis Rome’s magnificent Belle Epoque staircase,

one of Beus’s favorite spaces. “I never used the elevator while I stayed

there,” she says. ‘‘Why would you when you can walk

down those incredible stairs?”

“It was great to be able to pick my viewpoint, focus on what I thought was interesting and then sketch an outline. I sat for a long time watching people work – waiters, receptionists, butlers. It was a kind of theater; the staff move around these amazing spaces almost like dancers.”

Beus has traveled widely in the course of her work for major fashion houses and luxury brands, but this was her first stay in Istanbul, where she describes being “mesmerized” by the beauty of the architecture of the new St. Regis hotel. “The lobby is one of the most beautiful spaces I’ve ever seen,” she says. “The main chandelier is like a sculpture – the color changes during the day depending on the light. It’s really magical.”

Part of the brief for Butler Stories was to create original artworks depicting the hotels’ most impressive spaces, but Beus’s illustrations also offer a glimpse of a more intimate aspect of hotel life: snapshots of the daily routine, such as the serving of afternoon tea, the “sabrage” ritual (opening champagne bottles with a sabre), and “family traditions”, which might involve arranging a surprise treat for a guest’s birthday.

The most challenging aspect, Beus reveals, was getting her subjects to relax. “I would watch people working and then try to capture a particular moment. It was vital for them to feel comfortable. In a drawing you can really see when someone’s position is stiff and unnatural.”

As the title, Butler Stories, suggests, the project required Beus to shadow St. Regis butlers as they went about their work. “What I realized after talking to them,” she adds, “was that to be a great butler you really have to like people. It’s not enough simply to look elegant – it has to make you happy to make other people happy. That’s a very special quality.”

Your address: The St. Regis Florence; The St. Regis Istanbul; The St. Regis Rome

“I sat for a long time watching the waiters, receptionists and

butlers at work,' says Beus, 'It was a kind of theater – the staff move

around these amazing spaces almost like dancers”

The home of The St. Regis Florence is a beautiful 15th century

palazzo designed by legendary Florentine architect Brunelleschi

In 1571 Queen Elizabeth I of England was given the most advanced timepiece ever created. It was a small clock that could be worn on the wrist. In 2015 Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, presented what he referred to as “the most advanced timepiece ever created” to the world. It was a small clock that could be worn on the wrist.

Both Elizabeth’s “arm watch” and Cook’s Apple Watch are marvels of miniaturization. And yet youngsters of the iPhone generation might take one look at the queen’s mechanical bauble and wonder what the fuss was about. It could not, they might point out, respond to voice commands, measure its wearer’s heart rate, function as a contactless credit card or alert the sovereign to incoming emails – all of which Apple’s state-of-the-art gizmo can do, and more.

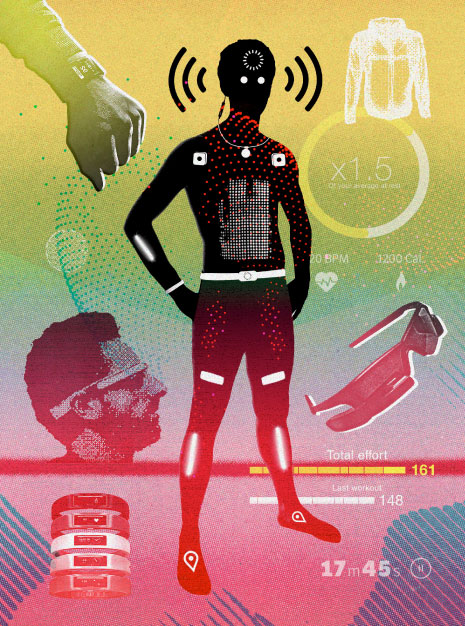

“Wearable technology” has come a long way. And the sector is set to go a great deal farther. How big might the boom be? According to Lisa Calhoun, founder of Write2Market, a technology PR firm, “Wearable tech is currently an $8 billion industry, projected to hit $50 billion in the next five years. With a change in image, the industry could accelerate and possibly even surpass that potential for growth.”

The wearables market is dominated by smartwatches and health- and fitness-related devices. At least in the short term these will remain the two biggest categories. When wearable fitness-monitoring devices created by companies such as Nike, Fitbit, Intel and Jawbone emerged a few years ago – measuring steps taken, calories burned, heart rate, skin temperature and sleep quality – they seemed to represent a move towards what has been termed “the quantified self”. In 2015 and beyond, expect to see further moves in the same direction, including motion-tracking socks and underwear, light-reactive jackets that glow in response to exertion, wireless devices for scanning blood-sugar levels, and shoes that can help runners manage their pace and navigate unfamiliar streets.

Meanwhile, other applications are being found for wearable technology. Car-makers are developing apps that will let people unlock and start their cars remotely using their smartwatches and phones. Airlines are investigating how wearable technology might help streamline the check-in process. Anxious parents can attach devices that use GPS technology to curious toddlers with a tendency to wander off. And sun-lovers can avail themselves of bracelets that monitor desired tan levels and swimwear that changes color to warn them when they are in danger of going from tanned to burnt.

Indeed, the point at which technology and fashion intersect is one in particular to keep an eye on. “In five to ten years’ time, all the little gadgets we have to carry around – like mobile phones, cameras or bracelets – will disappear and everything will be integrated into a garment,” speculates Francesca Rosella, creative director of CuteCircuit, which is at the cutting edge of fashionable wearable technology. CuteCircuit made its name with a “hug shirt” that mimics the sensation of being embraced when someone with the corresponding app sends the shirt’s wearer a text message. The brand is also known for its miniskirts and dresses that glow and switch between patterns, which have been shown off to striking effect by celebrity fans such as Katy Perry and Nicole Scherzinger.

But so far the highest-profile mainstream fashion label to express a keen interest in wearable technology is Ralph Lauren. Last year it launched the Polo Tech, a tightly fitted sports shirt that monitors heartbeat, breathing and stress levels. That data gets sent from the shirt to an app via a detachable Bluetooth-enabled box. (The shirt itself is fine in the washing machine; the box loaded with delicate biometric circuitry is not.) “The technology has evolved to a point where it can now be synthesized with clothing,” said David Lauren, Ralph’s son and the brand’s executive vice-president, on the occasion of the launch. “The goal now is to merge it into all kinds of clothing. It will be mind-blowing five years from now.”

Although the number of wearable devices is growing every day, the majority of consumers remain fitness fanatics. Yet studies also show that wearable fitness-trackers are apparently not as compelling as smartphones, with many users admitting to losing interest in and even abandoning their new toys after a short while.

On a technical level, another factor limiting the attractiveness of many wearable devices is their typically short battery life and inability to function unless connected to a nearby smartphone. With so many electronic gadgets to juggle already, why should consumers want to buy more – especially when their phones can already do practically everything wearables can?

Another obstacle is that eternal and, for the manufacturers of consumer goods, maddeningly unpredictable quirk of human nature: the perception of what is and is not cool. The rejection of Google Glass, smartglasses that overlay data and augmented imagery on what the wearer is looking at through their spectacle lenses, is a case in point. In principle, Google Glass is an exciting idea, and it seems likely that the technology will prove useful in industrial settings, making it easier, for example, for warehouse workers to locate and handle stock. But ordinary consumers were allergic to the product, perceiving it as not only creepy and intrusive but also, and most damningly, uncool.

Wearable technology’s true believers predict a future in which electronic devices worn on the wrist or neck will become part of every area of our daily lives, serving as a form of ID, allowing us to shop, navigate and communicate, as well as to gather and interpret data on our personal activity and wellbeing; in short, to provide what technologists call a “persistent digital identity”. We are certainly well on the way. But we have not quite arrived there yet. Elizabeth I’s arm watch is not entirely obsolete, after all.

When Mary Shelley sat down to write her letters home in the early spring of 1819, she had already fallen in love. The author of Frankenstein and the wife of the famous poet had arrived in Rome a few days before, and the city had seduced her. Basking in the warm Roman sun, contemplating countless masterpieces across two and a half millennia of history, she was enthralled. “The delights of Rome have had such an effect on me that my past life appears a blank,” she wrote breathlessly, “and now I begin to live.”

Mary knew well the Piazza del Popolo, the square in which I am sitting at the Caffè Canova, enjoying a croissant and the best coffee in the world. A wide oval, the piazza is framed by curving balustraded roadways and centred on fountains spewing curtains of silver water. To the south, twin churches mark the entrance to the city. On the opposite corner, by the Dal Bolognese restaurant, where film stars dine on Saturday evenings and cardinals have Sunday lunch, two carabinieri pose in uniforms that are more Gilbert & Sullivan than constables on the beat. Two nuns glide by, twins in wimpled black, passing a young couple locked in an embrace on the rim of the central fountain. The shadow of the obelisk that Augustus brought back from Egypt after defeating two of the great lovers of antiquity – Antony and Cleopatra – stretches across the cobblestones to touch my feet.

Cavalcades of ghosts roam this piazza. Before trains and airplanes gave us more mundane backdrops, the square was the grand stage for Roman arrivals. For more than 17 centuries, all those who made the journey to Rome from elsewhere in Europe – kings and popes, armies and emissaries, merchants and pilgrims – entered the city through the great Porta del Popolo opposite. Martin Luther lodged here while formulating ideas that would lead to the great schism of the Protestant Reformation. Queen Christina of Sweden – libertine, libertarian and lesbian – rode through Porta del Popolo opposite, waving to welcoming crowds, believing she was escaping the constraints of a northern throne for the freedoms of southern indulgence. Bonnie Prince Charlie – pretender to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland, and born in this city – paused here to splash his face in the fountains after another drunken night.

But the journeys and the arrivals that fascinate me are those of the early tourists, the travelers on what came to be known as the Grand Tour, a phenomenon of the 18th and 19th centuries in which gentlemen and sometimes ladies of means toured the continent to add some polish and sophistication to their manners and education. With its wealth of artistic treasure, Italy was always the highlight of these European journeys, and Rome, the ‘Great Crown of the Grand Tour’, the ultimate destination.

Among them were famous writers and artists. John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron all hurried across the cobbles of Piazza del Popolo. Stendhal, Algernon Charles Swinburne, William Wordsworth, Sir Walter Scott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Charles Dickens – all went “reeling and moaning about the Roman streets”. Henry James echoed Mary Shelley’s passion for the city. “For the first time,” he wrote to his brother on the evening of his arrival, “I live.”

The journey to Italy and to Rome started with the Alps, “those uncouth, huge, monstrous excrescences of nature”, according to one 18th-century traveler. Some visitors, like Horace Walpole, whose King Charles spaniel was carried off and promptly eaten by a wolf, rode mules along the snowy precipices. Others, like James Boswell, were carried in palanquins by sure-footed porters. Boswell was said to have crossed the Alps “with mingled feelings of awe and adulterous anticipation”. Italian women were one of the attractions of any journey through Italy.

Boswell was probably anticipating Venice, whose courtesans were famous. The Frenchman Charles de Brosses described them as a cross between fairies and angels; heroically, he tried eight in order to get a decent sampling. But nuns were generally considered to be the most passionate lovers in Venice; there was a famous incident of a nun fighting a duel with an abbess over a mutual lover. Someone should have told Boswell. His adulterous intentions towards a promising Venetian woman “of some social standing” met with a sad rebuff.

From Venice our travelers crossed the Apennines to Florence. The journey could be difficult (in one wayside inn William Beckford was offered a dinner of mustard and crow’s gizzards) but everyone loved the city on the Arno. As always, there seemed to be too much to see: one 18th-century guidebook listed 160 public statues, 152 churches, 18 guildhalls, 17 palaces, six columns and two pyramids, without even mentioning the countless paintings. Tired of the sights, Sir Horace Mann was fortunate to catch the Carnival with its masked balls and its bacchanalian amusements. “I have danced,” he cried. “Good Gods! How have I danced!”

As the travelers turned south to Rome they followed the Via Cassia of the Roman legionnaires and the Via Francigena, the centuries-old pilgrim route to Rome. Both led directly to the Porta del Popolo, where, stretching their legs, they marveled at the theatrical entrance to the city. But the piazza was hardly journey’s end. Rome, which Lord Byron called “the city of the soul”, awaited them.

I finish the last of my croissant and coffee and set off to follow the travelers on their ramblings around the city they knew as Caput Mundi, the Capital of the World. A short walk round the corner into the Via del Corso, once the scene of riderless horse races, brings me to the rooms where Goethe lodged. The great German writer came to Rome in search of classical art. But in the humble rooms in Via del Corso, where he once lay writing verses on his lover’s naked back, he found love, passion and erotic emancipation. By his own account, Rome and his love affair with his Italian mistress changed his life. “Eros has arrows of various kinds,” he wrote. “Some seem just to scratch us… others, strong-feathered and freshly pointed and sharpened – right to the marrow they pierce.” His love nest is now a small museum, the Casa di Goethe, and its exhibitions trace the transformations of the man known as the German Shakespeare. Pick up a copy of his Roman Elegies; erotic poetry was never so exquisite.

From Goethe’s apartment I cross to Via del Babuino and the entrance to Via Margutta, one of the most charming streets in Rome. Long associated with visiting writers and artists, it was home to people like Sir Thomas Lawrence, the president of the Royal Academy of Arts, who lived here in the early 19th century. It is the street itself, as well as its associations, that is so seductive. Rising rents have forced most artists to look elsewhere for studios, but this pedestrian backwater, with its small galleries and antique shops, retains the atmosphere of an earlier Rome. The tiny Osteria Margutta at number 82 is my favorite place for romantic candlelit dinners. Bring along a copy of Goethe’s Elegies to read over the dolci.

Back in Via del Babuino I’m on the trail of Keats, the tragic young poet who arrived in Rome in 1820. At the end of the street I emerge in the Piazza di Spagna, where the Spanish Steps, strewn with flowers, rise to the double spires of the church of Trinità dei Monti. In the 18th and 19th centuries the area was known as the English Ghetto. As early as 1740, Horace Walpole was complaining that the English in Rome seemed numberless; the Italians had taken to calling them milordi.

Just to the left of the Spanish Steps is one of their favorite haunts, Babington’s Tea Rooms, still serving English afternoon teas between the beveled mirrors and the palms. Not far away, in fashionable Via Condotti, is another of their haunts, the Caffè Greco. After two and a half centuries, the fittings and the paintings still evoke the long-lost world of the Grand Tour.

Hard by the Spanish Steps is the Keats-Shelley House, now a museum to the two Romantic poets. Already suffering from tuberculosis, a lovelorn Keats came to Rome in the hope that a sunnier climate might provide a cure. With its book-lined rooms, the house is a wonderfully atmospheric place. I climb the stairs to the narrow chamber where Keats lay day and night gazing at the ceiling that his friend, the painter Joseph Severn, had decorated with flowers for him. He died here, on a dark winter day in February 1821, barely 25 years old, still dreaming of his beloved Fanny Brawne, left behind in London. It remains one of the most moving places in Rome.

Back outside I climb the Spanish Steps to the district of the visiting French. Architects routinely praise the way the steps are visible from all angles. But the builder, Francesco de Sanctis, did not have aesthetic considerations in mind. “I will make the steps visible from everywhere,” he sniffed, “because the reverend fathers [of the French church atop the hill] have alerted me to the gross indecencies committed on that shrubbery slope by couples who often hide there.”

The French always have an eye for the best real estate, and the area at the top of the steps enjoys some of the finest views in Rome. I follow the Viale Trinità dei Monti to a wonderful Renaissance creation, the Villa Medici, “acquired” by Napoleon for the French Academy. Visiting artists are still granted studio space here, but for the general traveler there are tours of the apartments and the gardens that feel like a secret retreat. A little farther along the Pincio Hill is the Casina Valadier, named after the man who designed the Piazza del Popolo. Its elegant terraces are the ideal place for lunch with a view over Roman rooftops where domes rise like hot-air balloons.

Away to the left, you can see the white “wedding cake” creation of the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II, commonly called the Vittoriano, and just behind it, the Forum of ancient Rome. In the days when Latin and Greek were still part of a normal school curriculum, most travelers on the Grand Tour had read Cicero and Virgil, Ovid and Horace, and were thrilled to be wandering the streets where they had lived and died. Many enlisted the services of guides to show them around ancient sights. The great German guide Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who became the leading 18th-century authority on classical art, was much sought after. He was a man of considerable tact. Showing John Wilkes around the Forum, Winckelmann kindly pretended not to notice when he and his mistress, overcome by lust, disappeared for some moments behind a ruin. All the more obliging, Wilkes commented later, because he had to pass the interval with his mistress’s mother, “who had as little conversation as beauty”.

But no visitor is more closely identified with ancient Rome than Edward Gibbon. I climb the long steps to Michelangelo’s glorious Piazza del Campidoglio, centred on the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius. Just beyond the piazza in the far left corner is a balcony overlooking the ruins of the Forum. Gibbon came here one fateful evening in the autumn of 1764 in reflective mood. The sound of the friars chanting litanies in the Church of Santa Maria d’Aracoeli wafted across the piazza. As he looked down on the Forum “where Romulus stood, or Tully spoke, or Caesar fell”, he conceived the idea of writing The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, one of the seminal works of European history.

Keats’ great friend Shelley also found inspiration in Rome’s sprawling ruins. Shelley adored Italy and spent several years here, where his curious domestic arrangements – in addition to his wife Mary he seemed to travel at different times with two mistresses – didn’t seem to raise any eyebrows. The spring of 1819 found him lodged with Mary, Claire the “nanny”, and his son William in the Palazzo Verospi in the Via del Corso, not far from where Goethe had lived some decades earlier.

The Shelleys spent their mornings exploring the ruins and the art collections and their afternoons riding through the gardens of the Quirinale and the Villa Borghese, the latter still Rome’s great green oasis. In the churches, Mary wrote, “we see the divinest of statues and… hear the music of angels”. Shelley loved to wander the city alone by moonlight, when the evening breezes brought sweet aromas from the country. His favorite destination was the vast Baths of Caracalla, the most spectacular of Rome’s ruins. It was here, beneath the arches, that he wrote Prometheus Unbound.

I hop on the No. 3 tram from Trastevere to the Protestant Cemetery, one of the stops on Shelley’s moonlight rambles, by a southern gate of the city, close to the Pyramid of Cestius. “It might make one in love with death,” he wrote, “to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.” Pines and cypresses separate the rows of tombs. The colony of cats that has lived here for generations has its own charity box just inside the gate. You can find Keats’ grave in the far left corner, shaded by trees, inscribed with a single line: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

In July 1822 Shelley drowned after his boat capsized in a storm off the coast at Livorno. Mary accompanied his ashes across the Piazza del Popolo and through the city to burial in the cemetery. His gravestone is inscribed with Ariel’s lines from The Tempest: “Nothing of him that doth fade/But doth suffer a sea change/Into something rich and strange.”

It reads like an epithet for the city itself, the Eternal City, still rich and strange, still unfaded after the many sea changes of two millennia. For generations of visitors, Rome has been a revelation. No city in the world has been the destination of so many journeys, or has transformed the lives of so many travelers.

Your address: The St. Regis Rome

Bangkok has long been a compelling place to visit, a culturally rich Southeast Asian capital that has managed to retain a strong national identity despite rapid development. What has given the city an additional edge for luxury travelers today is that, as well as being home to gilded Thai temples, craft emporiums and markets rich in color and culture, it has developed a booming urban arts scene and remarkably sophisticated eating and drinking venues.

When exactly Bangkok changed from being a hedonistic backpacker paradise and temple city into a budding food and shopping destination is difficult to pinpoint. Some argue that it was the arrival of designers such as Ashley Sutton, who created the iconic Bangkok bars Maggie Choo’s and Iron Fairies, that has propelled the city into the future far faster than other tourist favorites such as Ho Chi Minh City and Phnom Pen. Others believe Bangkok’s rise to fame as the cool kid in Southeast Asia arrived when locals started to merge hip Western trends with local culture. “All the successful launches in the last five years have been of lifestyle establishments that have involved something else,” says Daniel Fraser, co-founder of luxury tour group Smiling Albino. “For instance, open art forums at night that also work as bars, restaurants that operate as art galleries and bars that double as performance theaters.”

The food, too, has evolved enormously in the city, he adds. “People always came for the street food, and still do. But now they might have street food at a market one night and a five-star dinner by a Michelin-starred chef like Joël Robuchon the next.”

As in many cities, some of the richest experiences, both contemporary and historical, are best accessed with the help of knowledgeable local guides or insider information. Here we offer a handful to make the best of your stay.

Design a custom suit

A trip to a tailor is now as synonymous with Bangkok as a dizzying ride in a tuk-tuk. Just like the tuk-tuks, tailors occupy practically every corner, jockeying for business from passing pedestrians. Enter Tailor on Ten, the antithesis of the typically crowded shop lined with fake designer fabrics. Run by Canadian brothers Ben and Alex Cole, the spacious store features private fitting rooms, on-site master tailors and fine Italian fabrics by manufacturers such as Loro Piana. What keeps international businessmen and ambassadors alike returning to Tailor on Ten is the attention to detail. Customers come for three fittings during a week and the Coles’ team personally selects every shoulder pad, interlining, button and thread used in the making of the shirts and suits. For men, sipping beer and crafting a new wardrobe or tuxedo gives them the ultimate kid-in-a-candy-shop feeling.

Suits from $400; tailoronten.com

Train with a martial arts star

On the outskirts of Bangkok, hard-bodied Thai men in brightly colored satin shorts enter the black-and-red-checkered ring at Luktupfah Muay Thai Academy for a full day of classic Muay Thai lessons with world-renowned trainer, Chinawut Sirisompan (known as Grand Master Woody). Spending the day with the Muay Thai pioneer, who was among the first to bring the sport to the West and is the founder of the Amateur Muay Thai World Championships, is equal parts history lesson and intense physical training. A day camp starts with a brief history of the sport and a breakdown of the rules and techniques before a warm-up run through nearby rice fields and villages. Back at the gym, there’s time to spar in the ring while a videographer captures the moves. When the grunting and combat is over, students can enjoy a Thai massage, time in the sauna and lunch before returning to Bangkok in a private car – with a few bruises and a new-found respect for the ancient Thai martial arts.

From $12 a session; luktupfah-muaythai.com

Fly over the city in a helicopter

The noise from the churning rotors quickly rises as the helicopter lifts above Bangkok’s crowded streets. The most shocking discovery of this 50-minute aerial trek is just how disorganized the Thai capital is, lacking the city planning, wide sidewalks and defined downtown areas of many major cities. But that lack of polish and orderly chaos is exactly what gives Bangkok its buzz, its magnetism, its charm. Whizzing above the Chao Phraya River, it’s possible to get a bird’s-eye view of the most iconic sights in town: the intricate canal systems, and the ancient Wat Arun and Grand Palace. Back on land, the journey ends with a private car back into the city.

About $1,600 for two, eastmeetswesttravel.com

Take Thai cooking lessons

Blue Elephant restaurant has long been Thailand’s unofficial culinary ambassador, showcasing the beauty and diversity of Royal Thai cuisine. Lessons are led by the restaurant’s leading chefs or, on request, the founder and executive head chef, Nooror Somany Steppe. Each student has a cooking station and wok, and time is spent both in the classroom and in the kitchen. A single morning’s lesson might involve taking an hour-long trip to the nearby Bangrak Market to shop for such typical Thai ingredients as bird’s eye chili and dried shrimp, then learning to cook four authentic dishes such as massaman curry with beef, pomelo salad, Thai fishcakes and a hot and sour soup. Lessons are in a beautiful colonial-style mansion, and at the end of the lesson students can feast in the elegant living room filled with dark rattan furniture and Asian artefacts.

From about $150, blueelephant.com

Tour the flower market

Pak Khlong Talat, Bangkok’s 24-hour flower market, is a place in which almost every visitor experiences a slight sensory overload. Exotic fragrances fill the air as fast-speaking Thais quickly exchange their crumpled baht bills for bushels of flowers. An astounding number of blooms come to the market daily from around Thailand, including orchids in myriad colors, roses, lotus buds sold chilled on ice and marigold blossoms strung into garlands. Navigating the maze of passageways and warehouse rooms is best done with a guide and, better yet, a botanist. The most renowned is Sakul Intakul, the director and creator of the Museum of Floral Culture in Bangkok, who specializes in flower art and installations. A tip: it’s worth buying not just flowers but a vase to create an arrangement for your hotel room.

From $800 for two; smilingalbino.com

Hunt for Asian antiques

House of Chao, a slightly dusty three-story antique house, is decked out with antiques and curiosities from Thailand and neighboring Asian countries including Myanmar, China and India. Known mostly to antique collectors and aficionados of teak furniture, the emporium harbors an assortment of genuine curiosities, ancient treasures, pseudo-antiques and impressive-looking replicas sourced by its charming owner, Khun Chaovanee, who also attends to their restoration. Among the ornaments, carpets, textiles, Thai silk and artwork there are some serious collectibles and one of Thailand’s largest selections of traditional Burmese furniture. Chaovanee is authoritative (and honest) on the provenance of her wares, and can happily arrange for goods to be shipped all over the world.

9/1 Decho Road, Silom; +662 635 7188

Meditate with a yoga teacher

With American founder Adrian Cox at the helm, Yoga Elements Studio has garnered a reputation for being not just the best yoga center in Bangkok, but one of the best in the world. Situated on the 23rd floor of a high-rise near to Chit Lom BTS skytrain station, the studio’s teachers instruct in vinyasa and ashtanga yoga in classes that run through the day from 7am until 9.15pm. Cox, a yoga teacher for more than 15 years, has devoted himself to the study of meditation, philosophy, Ayurveda and linguistics, and trained with gurus in New York City and India. In addition to taking yoga classes, he offers a meditation session to those who want to chill out completely on Saturday afternoons. For those who want to take the discipline further, he also offers a 200-hour teaching training course.

From about $15 for a drop-in class; yogaelements.com

Commission a bespoke table

Belgian former antique dealers, Pieter Compernol and Stephanie Grusenmeyer, set out to create a line of bespoke, hand-crafted tables after unearthing large antique wooden boards in a remote Asian village and deciding to remodel them. The result of their creative efforts is P Tendercool, a chic studio-cum-showroom near the Chao Phraya river that sells the sort of bespoke contemporary pieces that are snapped up by top interior designers around the world. Tabletops are made from antique wooden slabs salvaged from Asian homes or kiln-dried reclaimed beams from colonial buildings. Bases and legs are hand-cast from bronze, aluminum or brass and forged by expert Thai craftsmen. Those who don’t want to design their own furniture can choose from ready-made pieces ranging from dining sets and desks to stools, benches and consoles. International shipping can be arranged.

Your address: The St. Regis Bangkok

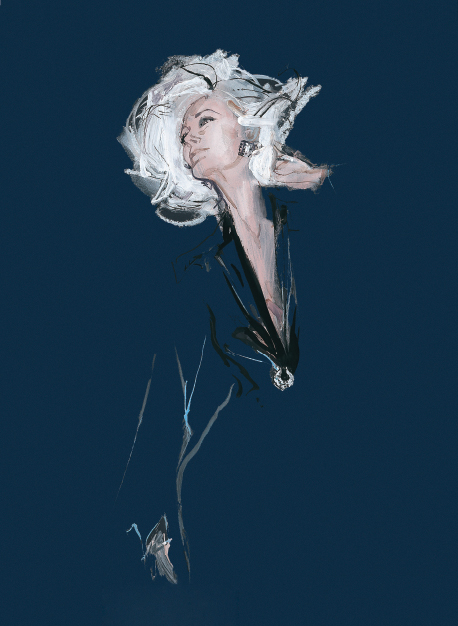

During fashion’s flirtation with Surrealism in the late 1940s, Carmen Dell’Orefice, still in her teens, found herself at The St. Regis New York on a wildly extravagant set designed by the self-anointed high priest of the movement, Salvador Dalí. Cecil Beaton, a friend of Dalí’s, who was working at the Condé Nast studio on Lexington Avenue that day, dropped by to check on proceedings (the photographer was the matinee-idol-handsome Horst P. Horst).

Beaton had returned to New York after a tour of duty as a war photographer and was staying at The St. Regis New York, where his neighbors were Dalí, his wife Gala and their pet ocelot, Babou. Knowing that the artist was on the lookout for a model and that Carmen could use the extra money, Beaton had introduced the two over lunch at Le Pavillon – later La Côte Basque – and Carmen had agreed to pose. It’s the way things happened back then. “He was a showman,” says Carmen of Dalí. “It was all a performance, but one he very much enjoyed. He pretended he couldn’t speak English, but that was just part of the ruse.”

Carmen was supposed to represent La Primavera – a painting by Botticelli also known as The Allegory of Spring – and to be naked to the waist. “That didn’t bother me,” she says nonchalantly, “and it didn’t bother him.” Of much more interest were the charcoal drawings of horses that littered the floor of Dalí’s suite. One day he offered her one in lieu of payment. “I was getting my regular $12.50 an hour, so I said I’d have to go home and ask my mother about it. Now, my mother wasn’t stupid, but we needed the money so badly. She said no.”

Carmen Dell’Orefice has dozens of extraordinary tales to tell, and since she is celebrating 70 years working as a professional model, this would seem to be the perfect time to share them. Born in New York in 1931 to an Italian concert violinist and a Hungarian dancer, she began modeling at the age of 13 after a bout of rheumatic fever and a preternatural growth spurt left her too weak (and too tall) to pursue her early passion for ballet. Deemed to be “too mature-looking” for Seventeen and Junior Bazaar magazines, she began her career as a high-fashion model under exclusive contract to Vogue. Within weeks Carmen was working with the defining photographers of the era: Irving Penn, Erwin Blumenfeld, John Rawlings and Horst. “They were mentors who provided a gateway to the rest of my life and the world,” she says.

While Carmen spent her days modeling designs by Charles James and Mainbocher, life at home was somewhat different; with her father absent, she assumed the role of breadwinner and was soon paying the rent on the fourth-floor walk-up apartment she shared with her mother on Third Avenue. There was no telephone (until Horst eventually insisted she get one), so Vogue would dispatch a runner whenever her presence was required.

Photographs taken in the 1950s show Carmen variously as a blonde bombshell à la Monroe (with whom she modeled hats for society milliner Mr. John), a raven-haired society swan, and everything in between. “I was a chameleon, a silent actress. I was never an ‘It girl’,” she says. Her career reached a high-water mark in 1957 when she shot the Paris collections for Harper’s Bazaar with Richard Avedon, under the fashion direction of Diana Vreeland and the all-seeing eye of graphic genius Alexey Brodovitch.

Although Carmen never officially retired from modeling, in the mid-1960s she scaled back her work to concentrate on family life. She had married for a third time and had a daughter, Laura (today a psychotherapist), by her first husband. When that marriage ended in divorce a decade or so later she found herself in need of a job and made tentative steps back into the industry.

At a party she ran into her old friend Norman Parkinson, who declared that she “didn’t look bad for an old bag”, and flew her to Paris for French Vogue, relaunching her career. The resulting pictures were a sensation and revealed a new Carmen: sexy, silver-haired and on the brink of 50. Her old agency, Ford, opened a new division specifically to handle her, and once again she was working with the greatest photographers: Helmut Newton, Patrick Demarchelier, Arthur Elgort, Peter Lindbergh and Steven Meisel.

Things had changed radically since her heyday, with models now expected to be personalities as well as faces. Carmen quickly adapted. She wrote a beauty book, hit the chat-show circuit, took cameo roles in movies by Woody Allen and Michael Cimino, and appeared on the catwalk in earnest for the first time in her sixties. Along the way she made it into the Guinness Book of World Records (as the oldest professional model).

I first met Carmen in April 2000 after pestering her agents to see if she would consider sitting for me. She eventually agreed, and we arranged to meet at her apartment on the Upper East Side in Manhattan. When I arrived she was whipping her hair into its trademark white squall, “to give you something to draw”. She posed all afternoon with Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald on the sound system, changing clothes, thinking things through, finding the line, and paying me the compliment of taking things seriously.

The drawings turned out well, and since then we have worked together whenever time and tide have permitted: in London, on the catwalk for Hardy Amies; in Paris, backstage at Dior; in Florence, in a deconsecrated church for Alberta Ferretti; and, coming full circle, last year at The St. Regis New York, almost 70 years after she posed for Dalí. For the occasion we hung one of Carmen’s own paintings by the artist on the wall, and felt the magic still.

What makes Carmen so inspiring to draw is that she has such an innate understanding of image-making. She has developed a sixth sense – or is it a third eye? – so that she sees what you see and “edits” herself accordingly for the page. There’s her beauty, of course, but that is just her opening play; she is also riotously funny, ribald when the mood takes her, and has the discipline instilled by decades on fashion’s front line.

Carmen has learned to be a gracious receiver of compliments, which is just as well, since they are the white noise of her life. “I know you hear this all the time,” gushed one lady of a certain age, when we were having dinner in New York recently. “I’ve never heard it from you,” was Carmen’s consummate reply.

And so she goes on. Standing sentinel at the age of 84 and staying true to her aim of representing her generation as positively as she is able. And although she is happy to talk about the past, she will not be pitching her tent there any time soon. There is a book to be getting on with, a documentary which is in the process of being edited, and the offers of work that keep on coming. “I am amazed by everything that is happening in my older old age,” she mused recently. “Perhaps today I am an It girl after all.”

David Downton: Portraits of the World’s Most Stylish Women is published in September by Laurence King

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Singer-songwriter Jamie Cullum’s obsession with jazz began when he saw The Fabulous Baker Boys. He was a 15-year-old piano prodigy at the time and had just started to get paid gigs in hotels. It didn’t matter that they were in Swindon, a small English town not noted for its rich jazz heritage. Teenage Jamie was just like his hero in the movie, the brilliant jazz pianist Jack Baker, though considerably less tortured.

Now 36, Cullum laughs this off as youthful folly. “When you’re a teenager, you grab on to certain icons to help you through the crippling nature of what it is actually to be a teenager,” he says. But in many ways he is still living the teenage dream. An acclaimed jazz pianist, he has released six albums and tours the world with his band. And this spring, he began a series of gigs Baker would have killed for: The Jazz Legends at St. Regis Series, an intimate set of live performances at St. Regis hotels around the world. Throughout the Jazz Age, the rooftop ballroom at The St. Regis New York played host to many of the jazz world’s biggest names, from Count Basie to Buddy Rich. Cullum has curated playlists and booked local acts to play alongside him as he celebrates St. Regis’ musical legacy.

Much of Cullum’s encyclopedic knowledge of jazz comes from his compulsive record-buying habit. “I’m almost permanently on the lookout for new sounds,” he says. As a teenager he dug everything from grunge to hip hop, but also loved to mine charity shops for old records. “I started picking up jazz albums by artists like Herbie Hancock, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk almost by accident. If there was a hip-looking dude in a kaftan holding a saxophone on the cover, that usually worked for me!”

This is how he acquired many of his favorite albums, such as Duke Ellington’s Money Jungle, which has “the rawness of a punk record”. He now owns somewhere between 5,000 and 8,000 records, as well as about 5,000 CDs. “I’ve cut it down a little bit, but it’s actually quite a modest amount,” he says. “I know people with 15,000 vinyls, easily.”

He is not one to pay hundreds of dollars for rarities – if you know where to look, you don’t have to. And thanks to all the touring, Cullum has gotten to know many of the world’s best record shops. So where’s good? “In Paris, there’s a place called Oldies but Goodies. It’s the best store for old records in the world: a floor-to-ceiling library. America has a lot of good ones, too. Like Joe’s Record Paradise in Washington – for rock, rockabilly, jazz, hip hop… all the good stuff. When I’m in New York, I spend the most at Colony Records in Midtown, not too far from The St. Regis New York. Or Bleecker Street Records, another amazing one for collectors.”

One question remains. How much does his habit cost him a month? “Mmmmm, that’s a hard one!” he laughs. “I couldn’t even guess.”

Your address: The St. Regis Washington, D.C.; The St. Regis New York