Travel and the Middle East were made for one another. Over the centuries – and no region on earth this side of Africa has been around for so many of them – the land has been criss-crossed by Nabateans, Romans, Crusaders and pilgrims. Its dunes and deserts have enticed writers and wanderers, from Victorian explorer Sir Richard Burton to TE Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia), while its Byzantine mosaics are still points of pilgrimage for modern travelers.

Having only ever studied Jordan – as Edom – during the course of a theology degree back in the mists of the 1980s, I thought it was high time I joined the caravan of explorers, mystics, dreamers and divines. They went on foot and by camel. I used these too, and a horse, and a nice, comfortable, air-conditioned 4WD. My mission: to see the ancient – and to arrive at the modern, and make contemporary sense of these biblical lands.

I crossed the Allenby Bridge from the West Bank behind buses heading to Mecca. Behind me, Jericho; beneath me, the River Jordan; a little way along on my right, Mount Nebo, from which Moses was allowed a view of the Promised Land. Not bad for a start. From here, the Jordanian river Kazem followed the magnificently dubbed though meandering King’s Highway south, following the contours of the Dead Sea Rift. At Madaba, I saw a large fragment of a map of the Holy Land made for an unknown Christian community in the 6th century. Jerusalem, Bethlehem, the Dead Sea and Nile Delta were all clearly depicted. What could be more stirring to a travel writer than an exquisite map, laid out on the floor of the Byzantine Church of Saint George, linking faith with landmarks and long journeys?

We traveled slowly for 220 miles all the way down to Wadi Rum, passing through arid plains and desert canyons. I saw few major towns and no cities, but plenty of shepherds and goatherds, donkeys and camels, as well as numerous Bedouin encampments. The land was parched and bleak. But wherever a trickle of water persisted, crimson poppies and black lilies – Jordan’s national flower – had burst through the dun crust.

I saw an old steam train left sleeping on the Hejaz railway at Wadi Rum – a southern, narrow-gauge spur of the old Orient Express. Here my path diverged from the great thoroughfares of Arabia as I made for a tented camp at the foot of a sandstone massif. A hot towel and fresh pomegranate juice awaited, as well as a basic if spacious Bedouin tent. Set amid a maze of monolithic rocks, this was to be my home for three nights; the first one began with a beautiful moon and a delicious barbecued lamb and meze supper around an open fire.

Deserts are utterly formless at first, and it takes time to get your bearings. A dawn drive in a sturdy 4WD took me first to a row of towering peaks nicknamed the Seven Pillars of Wisdom after the book of that name by TE Lawrence. There were no roads, but the driver-cum-guide followed ruts in the sand, which took us to high viewpoints, down through broad Martian valleys and into narrow natural cuttings dotted with tiny oases.

In the morning the heat was mild enough to set on short solitary walks. My drivers had the good sense to give me space and time to enjoy the silence, the surreal rockscapes and the play of the light on the mountains. I hiked to see the low-slung redbrick ruins of a Nabatean temple dating from the first or second century AD. The Nabateans were an Arab people who spoke a language related to Aramaic – Jesus’ native tongue – and ran a large trading network across the Levant. As well as inscriptions in their own language, Latin writing has been identified on an altar while marble columns were overlaid with graffiti in a poorly understood proto-Arabic tongue known as Thamudic.

From such sites sprung many European languages, as well as the fundamentals of Western culture. The temple is believed to contain remnants from the 14th century BC, when it was dedicated to two Mesopotamian deities: Hadad, the god of thunder and rain, and Atargatis, goddess of fertility, fruit and foliage. Standing behind one of the low walls and looking out over a plain littered with rocks and tufts of dry grass, I could imagine generations of locals looking up to the cloudless sky, yearning for rain and a few green shoots to feed a goat or camel.

But, lo and behold, just a little way along from the temple were springs bursting from the ground, framed by mint bushes. Close by was another waterhole shaded by green-leaved trees and ferns. In his Seven Pillars, Lawrence recalls pausing here to “taste at last a freshness of moving air and water against my tired skin. It was deliciously cool.

It was indeed, but there was so much else to see. I walked up to an outcrop, and then through another narrow wadi – or ravine – dotted with more pools, before joining the driver and continuing on to the Canyons of Umm Ishrin – the “Mother of Twenty”, supposedly named for 20 Bedouins killed on the mountain, or a mad, bad woman who killed 19 suitors before settling on the twentieth. On several rocks I saw depictions of Lawrence of Arabia, looking suspiciously like Peter O’Toole. Fittingly, the passage of the archaeologist-cum-military man-cum diplomat through these parts is largely shrouded in mystery.

Camels and hot tea welcomed me back to the tented camp, where I was able to shower and sit back and take in the deep peace and the huge dome of the darkening sky. There was electricity, hot water and beer, and my tent had a ceiling, but it still felt right to be in the desert. Little wonder that the most famous book in Arabian history is dedicated to the night – or that dreams figure so prominently in the region’s legends.

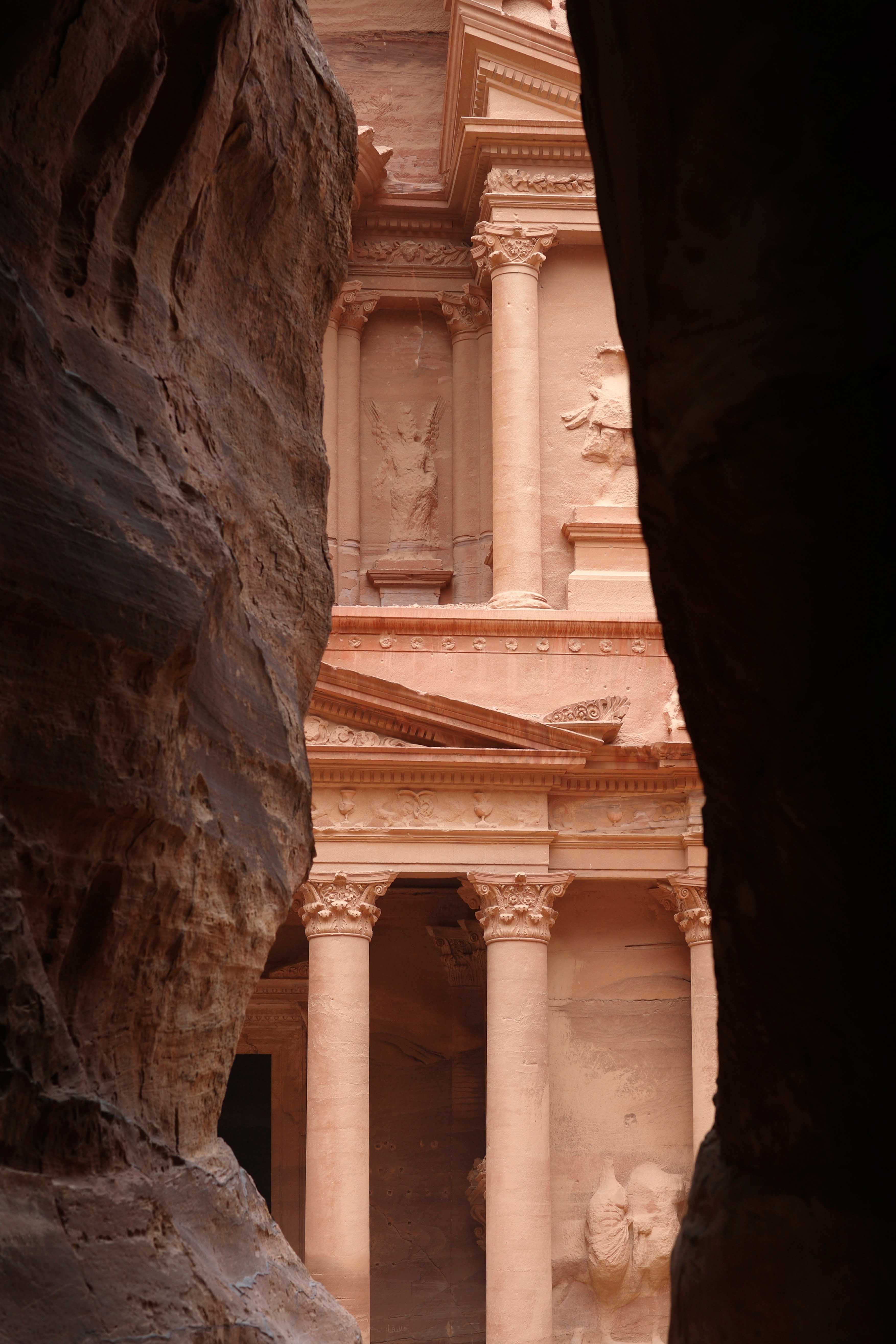

The canyons and ravines of Wadi Rum shaped only by weather and age, are a sort of divine overture for my next stop, Petra, where human craft has taken the raw material of sandstone and created one of the world’s true wonders. Desert travelers like to invoke Shelley’s Ozymandias. Well, Petra is an antidote to the expectation of decay. Where there might have been ruins and the scattered sands of time is truly spectacular architecture, carved out of the rocks – or perhaps “into” is more accurate. For this famous city, built as early as the 4th century BCE as Raqmu, the capital of the Nabeatean world, is like the imprint of a powerful imagination that saw shapes where others saw only cliff walls and untidy lumps of dead rock.

The path into the site, known as the Siq or “shaft”, follows a narrow, winding gorge through towering rocks. At times it’s barely ten feet wide, and is narrower at the top than the bottom; as you step from shadow into light, and then back into the murk again, it feels as if it was built for theatrical, rather than defensive, purposes.

On exiting the cleft – a geological fault smoothed by water – you meet with Petra’s stunning centerpiece: the Treasury, or Al-Khazneh in Arabic. You might know the colonnaded Greek-influenced facade from its appearance in the 1989 film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. The name refers to a local legend that bandits hid their loot in a stone urn placed high on the upper level. But the building was originally built as a mausoleum and crypt. The wind and seasonal rains have eroded many details but archaeologists have located mythological figures representing the afterlife, as well as dancing Amazons with double axes, and Castor and Pollux (twin brothers from Greek and Roman mythology).

Pliny wrote of Petra’s importance as a trading crossroads. As I walked on to visit dozens of rock-cut tombs, temples and a Roman-style theatre – the Romans occupied the site from 64-3 BCE – I began to get some sense of just how big and permanent, not to mention affluent, it must have seemed to its original residents and travel-weary visitors. Under the noonday sun, the 800 steps up to the Ad-Deir Monastery were slow going but at the top was another beautiful classical facade. Once it would have been a major crossroads linking China with Rome. On the main colonnaded street there was space to think and wonder: for centuries, caravans laden with silk, spices, incense and other exotic wares could be stored and animals rested safely here. Once a tax was paid, the merchants were free to continue their journey west or east.

Though UNESCO-listed Petra receives some 500,000 visitors a year, making it Jordan’s number-one visitor attraction, it’s expansive enough not to feel cramped. Once you’ve seen the major architectural landmarks, your gaze falls on shadows, caves, crevasses and windows offered by rocks that afford surprising vistas over the complex. Too many people rush through; I’d recommend a morning and then a late afternoon, to see how the sun works its own wonders on the sandy rock. You can easily escape the hubbub and the donkey-ride sellers, and there are several cafés and a restaurant serving delicious falafels. You can even pop back after dark for Petra At Night, when thousands of candles are lit in front of the Treasury for a session of music and storytelling.

Over the course of their long stewardship, the Romans diverted most of their lucrative trade routes away from Petra. That’s one of the main reasons it was overlooked even during the age of the Grand Tour. The site celebrated the 200th anniversary of its rediscovery – by Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt – in 2012. Those two centuries saw seismic political shifts across the Middle East and the establishment of many new nation states from former tribal territories. Jordan, which became a British protectorate and then gained its full independence in 1948 as the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (shortened to Jordan the following year) is one of these.

The drive from the ancient capital of the Nabatean empire to its modern capital, Amman, takes only three hours on Highway 15 – the main trunk road. The city sits in a deep bowl, its residential neighborhoods of cream-colored blocks spread over the slopes, with the main commercial centers along the lower reaches. More than four million people live in the fast-growing city (there were only about 5,000 in the 1920s), and the expanding sprawl now stretching over 19 hills, with many suburbs hidden behind the high ridges.

Amman lies close to ’Ain Ghazal, one of the oldest settlements in the near east, and stands on the site of the Greek city of Philadelphia (meaning “brotherly love”. As a Beta city on the global index, a cosmopolitan and liberal cultural center, an important banking hub, and a tourist destination popular with Arab and European travelers, it has risen to prominence with remarkable speed.

The best overview by some way is from the Citadel, a collection of Roman, Byzantine and Umayyad ruins that sits at the top of the city’s highest hill, Jebel Al Qala’a. The most significant extant structures are the 2nd century Temple of Hercules and partially reconstructed Umayyad Palace, but the poetry resides in the juxtaposition of ancient columns, podiums and arches – which act as a series of frames – and the modern apartment blocks beyond. A wonderful breeze made a walk around here late in the afternoon especially pleasant, and as there were only two dozen visitors spread around the extensive site, I could easily find tranquil spots to sit and stare. As at the Tels of Palestine, you have a strong sense of being on top of layered history, of belief systems and world-views that come and go. The feeling was compounded when I had one of those rare epiphany-like travel experiences – when the call to prayer commenced around the city, and live voices and recorded ones overlapped and echoed all around the valley.

There are regular evening festivals and concerts at the Citadel. As they’re the only way to see the site, and those views, after dusk, keep an eye out in the local listings via your concierge.

Down below is a hillside amphitheater from the same period as the temple. But I was ready for some 21st century city life. In Amman, there’s plenty of this, from the American-style eateries, power lunch and realpoliticking rendezvous of the western hotel districts, to the slick coffee shops and trendy bookstores of Rainbow Street, to the throbbing heart of downtown, where you can take your pick between old markets, traditional food stalls – Jordanian beef and pasta, bean dishes and fresh khubz breads are classics of Levantine cuisine – and street traders pulling carts loaded with olives, tomatoes, peppers and fresh juices. At times, its energy reminded me of Cairo, but it’s far less hectic and less dusty. It’s also untouched by mass tourism, a rare thing in a major capital.

The local Carakale microbrewery claims the Sumerians invented beer some 5,000 years ago and it is merely bringing it home. Around Darat al Funun, I found a fabulous contemporary art space. These are not the delights one expects to discover in an Arabian city. In the new Abdali district, two million square meters of office space are being developed to transform Amman, a safe and strategically important city, into a business hub. The blurb declares the project’s aims of “catapulting Amman into the 21st century and placing it on a par with most of the world’s renowned city centers”. Well, from Petra we know what happens to those in the end – but right now, Amman, and Jordan are happening and hopeful.

Your address: The St. Regis Amman