Iris, you were born and raised in New York, right?

I was raised in Astoria, Queens, and lived there until I married. My grandparents were settlers, actually, and caught the boat here from Long Island.

What memories do you have of coming to the city as a child?

Well, the city was the mecca. You would go there for shopping, or an event such as the Easter Parade – everybody in their spring finery, looking swell. In those days you wouldn’t see a person walking on Fifth Avenue without a hat and gloves. Today you’re lucky if they have shoes.

I remember a story you told me about your first experience shopping alone in the city…

Yes, I was 11 years old. It was Easter time and I needed a new outfit and bonnet, but my mother had no time to go shopping with me. So she gave me $25 to go into the city by myself. I went to S. Klein and found a dress that I just flipped over. All silk, poet sleeves, with a tie front, for only $12.95. I gave thanks to God and $12.95 to the cashier, and then went to A.S. Beck and got a smashing pair of shoes for $3.98. I had enough left for a nice little lunch and the bus home. My mother approved of my sense of style and my dad approved of my economical choices. My grandfather, who was a master tailor, was the only one who was not impressed.

Where were the memorable places that you lived in New York?

After I got married I moved into the city. I haven’t moved around that much, but before living here, we had a great townhouse on 79th Street. What we had in charm we lacked in plumbing. Nothing worked, but it was fabulous.

In what decade or era would you say New York was at its most elegant?

The late 1940s or 1950s, before the youth revolution. It was glamour; glamour doesn’t exist any more. People like glamour – especially men. I think men are more romantic than women, anyway.

Did you have any favorite spots in the city during that era?

Oh, there was fabulous nightlife, glamorous clubs like the Copacabana – where, if you were lucky, you could sit ringside and touch Frank Sinatra. Great jazz clubs, restaurants… Henri Soulé ran an extraordinary French restaurant called Le Pavillon. They all had dress codes – you couldn’t go in looking like a slob. It was nice to have people looking elegant. They always had a coat and tie rack for men who came in without them, and nothing would fit, so they’d sit there looking like the village idiot or a grade-school dunce. There was also Ben Marden’s Riviera in New Jersey. Everyone used to go. Lucille Ball was in the chorus. People also entertained at their homes beautifully. Guests came dressed to the nines. There was an article of clothing called the “hostess gown,” which you don’t see any more.

Did you frequent any of New York’s great jazz clubs?

El Morocco and the Stork Club. Fifty-Second Street was very important in the 1940s – the whole street, with one place next to another. I had a boyfriend who was mad for Billie Holiday so we used to go there all the time.

Do you have any fond memories of The St. Regis New York?

It was always a very beautiful hotel, and we used to go to the King Cole Bar there. It was a place for people to meet.

When you’re in New York these days, where do you like to go? We love to eat at

La Grenouille – it’s very old-world, very elegant. People come well dressed, the floral arrangements are spectacular and the food is divine… and yet it’s very natural. Some of these new restaurants that are so la-di-da are very pretentious.

Where do you like to shop today in the city?

I don’t shop very much. I don’t need to shop, I’ve got so much. But New York does have great discount stores, like Loehmann’s, and great sample sales.

What’s a highlight of your career?

We did major work at the White House, through more than nine administrations. We did many historic restorations: the Renwick Gallery, Blair House, the Senate, the State Department, Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace and the Decatur House, among others.

At 91, you have a whole new career as a spokeswoman, model, teacher and fashion icon…

Oh, it’s hysterical – the other night I did a personal appearance at Bloomingdale’s for my new handbag collection, and people were lining up. I’m the same as I ever was but all of a sudden I’m cool. It’s almost embarrassing. My husband and I think it’s very funny, but I also think it’s very sweet. I’m touched that at this stage of my life I’m having so much fun.

What projects are you working on?

I’ve done a line of sunglasses and readers for Eyebobs. I have a collection of purses called Extinctions, and a new line of shoes for HSN. I did a collection with MAC cosmetics and I’ve also been working on a perfume. I teach visiting students as a professor for the University of Texas, which keeps me very busy.

How did you feel when MAC approached you?

I thought it would be fun. When I do these things I really put work into it, choosing the colors and textures. I don’t just put my name on it. And a bonus is that I’ve met some very nice people from it.

Do you feel that you have helped in some way to alter the perception of ageing in popular culture?

I hope so; I think so. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I’ve become so popular, because I’m so old. I’m a cover girl in my dotage, a geriatric starlet. The world’s oldest living teenager.

What do you love about being in New York?

There’s no place in the world like New York. If you can’t find it in New York, it doesn’t exist. It’s the heartbeat of the world.

What advice do you have for someone visiting New York?

You have to be like a sponge and soak it all up. It’s a walking city with some of the best museums and shops, with everything you might want to buy, whether you need it or not. Every kind of food you might want to taste is here. And it all exists in all price ranges. What’s the Sinatra song… if I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.

So, where do you want to retire?

I don’t want to retire ever. I think retirement is a fate worse than death.

advancedstyle.blogspot.com

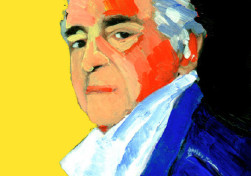

For a privileged few car lovers, high-end custom-design is making their fantasies a reality. The luxury brands are taking what used to be known as the “options list” in car design and offering exhaustive “personalization”. We’re talking here about ways of customizing your new motor to make it utterly unique, and the likes of Bentley, BMW, Ferrari, Aston Martin, Lamborghini, Mercedes, Porsche and Rolls-Royce are only too happy to oblige. A comparison with the famed tailors of London’s Savile Row is apt, not least when it comes to Ferrari’s interpretation – it has named its custom-design plan “Tailor-Made”. It’s the vision of Lapo Elkann, the charming high-flying grandson of Fiat kingpin and style icon Gianni Agnelli. Elkann calls himself a “freestyle entrepreneur”, and it’s his idiosyncratic approach to life that runs through Ferrari’s Tailor-Made concept.

In dedicated ateliers annexed to the main Ferrari showrooms around the world, clients can choose between “Classica” (retro styling from the 1950s and 1960s) and “Scuderia” (racing design), or let their imaginations run riot with “Inedita”. Pinstriped seats, cashmere roof lining, or carbon fiber and titanium trim – it’s all possible. “Today, luxury has to be open to new materials and new elements,” Elkann says. “If you’re spending that sort of money, you want the freedom to make the product look the way you want it to look rather than the way the company does.” While Elkann is something of an iconoclast and revels in the possibilities of high-tech new materials, tradition still plays a role. Ferrari suppliers include the celebrated furniture designer and materials experts Poltrona Frau, whose mantra intelligenza delle mani (clever handcrafting) informs the distinctive interiors of today’s Ferraris, and is crucial in Tailor-Made. “There is an almost infinite number of colors for our leather,” the company chairman Franco Moschini says. “There are now more than 90 colors compared to the five or six in the past. The skins are analyzed individually, because each animal is different and has lived a different life.”

Another Tailor-Made supplier is the Piedmontese fabric-maker Vitale Barberis Canonico, whose work with the company is more akin to that of a tailor than an industrial partner. And in a nod to Ferrari’s early days in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when handcrafted bodywork was made in ultra-low volumes for the aristocracy, films stars and industrialists, the company’s Special Projects division will design an entire car to your personal specifications. Eric Clapton is one of the Ferrari clients to explore this avenue with his SP12 EC. Was overseeing the design an enjoyable process? “Oh, unbelievable,” he says. “One of the most satisfying things I’ve ever done. There will never be anything like this again. This is me aged seven listening to [F1 drivers] Fangio and Ascari.”

Victoria Beckham is another big name to turn if not designer exactly, then specifier. Her 2011 limited edition of the Range Rover Evoque comprised only 200 units worldwide, yet despite costing around $128,500, it was an instant sell-out. A hot brand, superstar name and custom design all aligned with a genuinely desirable product, underpinning the marketing voodoo. In matte grey, with rose gold accents inspired by the men’s gold Rolex that her husband David had given her, and with a cabin trimmed in highly desirable buttery aniline leather, the VB Evoque is a notably tasteful example of limited-edition design. “I like to think outside the box,” Mrs. Beckham told me at the car’s launch in Beijing. “Why shouldn’t I design a car? When Gerry [McGovern, Land Rover’s design director] approached me to do this, it was certainly a challenge. I’d never designed a car before, so I think I brought a naivety to the project, though I’ve enjoyed customizing the cars David and I have bought over the years. I didn’t want a car that was particularly feminine, I wanted something that David also wanted to drive.”

Custom car design is a global trend, but individual countries’ traits can appeal across borders. A yearning for authenticity is one of the things that most commends say, Bentley to the booming Chinese market. British luxury automakers have a rich history in wood, leather and marquetry, and as the brand’s chief interior designer, Robin Page, puts it: “By the time you work out all the options [of materials] and all the combinations, there are millions of scenarios.” In fact, Bentley has arguably the richest history in custom design. Its Mulliner division offers “specialist personal commissioning,” a promise that is backed by a relationship that goes back almost a hundred years. The division is named after H.J. Mulliner & Co, the coachbuilder that the company founder W.O. Bentley asked to create the bodywork for his 1919 EXP1 prototype. Mulliner originally built Royal Mail carriages in the 18th century, and handcrafted saddles before that.

This sort of backstory plays well in emerging markets. “Craftsmanship and attention to detail is what defines British design,” Aston Martin’s chief designer Miles Nurnberger says. “We’re extremely creative, but we mix that with a pragmatism. German design is very pragmatic and very exacting, but can lack creativity. French design is creative, but might lack refinement or execution. British design strikes a good balance. We like modern architecture, but we also like quite homely things and comfort. There’s purity to British design, and it has honesty. Others might use something that looks like metal, but we actually use metal.” Gavin Hartley is head of custom design at Rolls-Royce, a company that has been working in the field for decades. “Whether it’s a house or a yacht, our customers don’t generally choose from lists,” Hartley says. “They’re beyond conforming to what other people might think. It’s an opportunity for dialogue with individuals, to allow them to pursue their own ideas.

We’re harking back to the early days of motoring, to the coach-building era, when there was less standardization and more choice. “Different rules definitely apply, and it often makes you question what good taste actually is,” Hartley continues. “You might think you are always right and everyone else is wrong, but in this business you are constantly challenging the arrogance of that assumption. But the people who come to us want a Rolls-Royce sort of solution, so it tends to be consistent with what we want to do – which is excellent, beautiful engineering.” Fortunately, as with other areas of automotive design, there is a notable trickle-down effect: the runaway success of the latest Mini, Citroën DS3 and Fiat 500 has democratized custom car design. Mass-produced they may be, but none is identical. Sustainability is also important: recently, the Peugeot Onyx concept car showcased an interior trimmed in felt and recycled newspaper so thoroughly compressed that it felt like wood. And even if the exterior matches a thousand other models, the endless possibilities for creating something unique on the inside provides a particular satisfaction, the feeling of knowing that no one else possesses anything like it.

Your address: The Bentley Suite, The St. Regis New York, a collaboration bringing the St. Regis and Bentley partnership to life.

1. Driving down to Troon, Scotland, 1956

I left the RAF when I was 19, but I couldn’t afford a car until I was 26. It was a Fiat 600, and my very first journey was from Glasgow down the west coast of Scotland to a seaside town called Troon. I’ll never forget the feeling, just me in my new car on a sunny day. Because it was Italian, it was a bit sexier than a British car – a chance to get the prettiest girls. Happiness.

2. The Berlin Wall goes up, 1961

I was sent to Berlin for the London Daily Express, and we knew something was going on as the city was being systematically closed off. The wall went up quickly, the barbed wire and the barricades encircling the city. I went back in 1989 for Life – I never thought I’d see the Berlin Wall come down in my lifetime. I’m glad I was there to see it.

3. Following the Beatles to Paris and America, 1964

One night in January 1964 I got a call from The Express picture desk to go to Paris to photograph the Beatles. I was a bit annoyed because I had no interest in photographing pop stars. But as I walked into the hall they started to play All My Loving, and it was electric. I knew I was on the right story. My

favorite picture of the Beatles having a pillow fight was taken in Paris. Within two weeks I was on a plane to America with them for The Ed Sullivan Show. The Beatles changed my life because America was a fascinating place to be in the 1960s; after that, I never came back.

4. The Meredith march, Mississippi, 1966

The Civil Rights Movement was at its height when I drove to Tuscaloosa,

Alabama, HQ of the Klu Klux Klan. I knew this was going to be dangerous, but it was my job. I met the grand wizard, Bobby Shelton, and attended Klan meetings with him. I followed the whole march; I went to rallies, I was tear-gassed, saw beatings, hid film in my socks. When I met Martin Luther King, I said to him, “This is just awful.” And he said, “It is awful being a black man in this country.” Jobs like these were journeys into the heart of America.

5. The assassination of Robert Kennedy, Los Angeles, 1968

I grew to like Bobby Kennedy immensely. He was fun to be with on the campaign, very easy to work with. When he was shot in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in LA, I was 12 inches away from him. It was chaos and people were punching me in the head and shouting, but I just kept moving, trying to get the shots. I photographed his wife Ethel screaming, and people said, how could you do that? He was someone I cared about. When something like this happens you know you are recording history. The picture of the straw boater is one of my most dramatic. This was Bobby’s blood. This was the end of the road.

6. 9/11, New York City, 2001

By the time I got down to the site, the second plane had hit. There was dust and debris everywhere and the police weren’t letting anybody through, so I took my pictures from the perimeters. Lots of photographers are suffering now from what they inhaled that day, so in a way it was a blessing for me, but I had to be there to see what happened.

7. Returning home to Glasgow, Scotland

Glasgow is my home, I love to go back and smell it. It has a rough and tumble about it that is similar to New York. But no year is complete unless I go to Troon for a walk along the beach and have an ice cream or some fish and chips and look across to the Isle of Arran. That to me is Scotland. I get excited just getting on the plane.

You can’t mistake the Beijing West Railway Station. A massive, plain-face building broken in the center by a cavernous archway, it is one of the capital’s throbbing transportation hubs. Colorful little pagodas are perched on the roof, and the effect is a kind of hybrid of the Pentagon crossed with Disneyland. But the station handles a quarter-million passengers every day, and on Chinese holidays, when half the country seems to be on the move, it can manage twice that number. Even at nine o’clock on this weekday evening in spring, the place is teeming with travelers.

Passengers for Urumqi are shunted into one huge waiting hall and passengers for Kunming into another. Those bound for Tibet jostle into Hall 5, standing room only. In the crowd, I’m reassured to spot two Buddhist monks in saffron robes, and I figure that they must know where they’re going, at least in a temporal sense. When the departure is announced, the gates open and the crowd cascades down a stairway to the platform below. There is the usual last-minute mayhem of passengers finding their places. Almost all the travelers are Han Chinese with a sprinkling of Tibetans and a half-dozen Westerners. Everyone carries suitcases, backpacks, plastic bags and roped-up bundles. I find my sleeper car and my compartment: two berths below and two above with a narrow passage between. Shrewd beyond my years, I have purchased all four places, an indulgence for the sake of privacy as well as space to store my gear for this three-day trip. Beneath the large window is a small, fixed table. An arrangement of dusty artificial flowers sits on top. There is a tiny reading light at the head-end of each bunk and a television screen set into the wall at the foot-end. The Chinese are putting a lot of effort into their long-haul passenger service and a pair of hotel slippers is tucked into each bed. I’m impressed, and I feel pretty well off. Spot on time, the engine pulling 18 cars glides out of the station. A forest of lighted apartment towers passes by on either side of the track and I see that some of the narrow alley markets are still doing business at this late hour. But then, suddenly, as if a curtain were lowered on these urban scenes, we are in the countryside and the Chinese night closes in around us.

The rhythmic click of the rails and the sway of the car become a lullaby. The Beijing government has invested vast sums of money in its national infrastructure and the rail network is a prime beneficiary. There are already more than 56,000 miles of track, but the plan is to lay half as much again by the year 2020 at a cost of some $675 billion, and high-speed trains (200 miles per hour) have been introduced on several sections. Even more ambitious, the Chinese have imagined a high-speed train eventually hurtling from Beijing all the way to London in four days. For the Chinese, the purpose of all this investment in rail is partly political: to strap together a far-flung and disparate country which has always been susceptible to centrifugal forces. It’s also economic: the rich mineral and coal deposits of western China can be efficiently funneled eastward by rail to the industrialized regions of the of the coastal hinterland. And with passenger traffic generously subsidized, the entire network represents a colossal national expenditure. Developing the Chinese railroad system has been a daunting undertaking. When the Americans and Russians constructed their great rail systems, the respective landscapes only occasionally presented serious obstacles. But more than half of China’s surface is rugged and mountainous. In this twisted terrain, every mile of track is a challenge.

We arrive in Xi’an with the dawn. Passengers disembark. Others board, and we’re on our way again. The track here swings north west to skirt the forbidding mountain ranges lying directly west. We follow the course of the Wei River, the broad, shallow, muddy stream that cuts through the dusty loess of the central highlands and eventually becomes the Yellow River. We are in the real heart of the nation, for it is from this region, Shaanxi Province, that the First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, emerged and unified the country in 221 B.C., but who is best known for his extraordinary Terracotta Army of soldiers that escorted him into the next life. The lower course of the Wei is fertile on both alluvial banks. Green fields of rice and millet roll out to the distant foothills. By the time we reach Baoji, however, the broad, well-ordered plain suddenly seems to collapse into a jumble of crumpled earth, and the valley narrows. On either side now stand bare sandstone mountains with sharp ridges, like a dinosaur’s backbone and flanks, gouged and jagged from eons of wind and rain. Here, rice is still grown, but cultivated in helter-skelter paddies, some carved into narrow terraces leaving others to cling to the steep hillsides. From the 21st century we seem to have slipped into the 18th. Villages are a collection of mud walls, small courtyards and tile roofs. The primary source of power is the ox. The train switches back and forth across the tumbling river, and in and out of innumerable tunnels. And we are climbing. In the outskirts of Lanzhou, the public address system in the compartment jumps to life.

After a long announcement in Chinese, a recorded translation in English is played. Passengers are informed that Lanzhou is a thriving city and “a friendly stopping point connecting on the way to Africa.” But there aren’t too many travelers on the train who look as if they’re bound for Kampala or Bamako, and Lanzhou, through the window, seems like yet another of China’s nondescript, colorless, over-built cities. At the station, more passengers get off than get on, and I notice a telling attrition rate as the train heads for the remote, high-plateau country and the gateway to Tibet.

I have brought along abundant supplies of nutrients: bags of dried fruit, bars of dark chocolate and a treasured jar of peanut butter. But on the second evening, I decide to see if I can get a place in the normally crowded dining car. To my surprise, I find the car empty and I don’t know whether that’s a good sign or a bad one. I order “eggs with edible fungus”. Inedible fungus is probably cheaper, but the fare is tasty, and the bill, including an excellent Chinese beer, comes to $4. Shortly after returning to the compartment, there is a knock at the door. The attendant hands me a long coil of plastic tubing, and with gestures he indicates it’s for the oxygen outlet above my berth. The straight end of the tube plugs into the socket and the splayed end into your nostrils. But I have already decided to forego the convenience of the oxygen supply unless absolutely necessary. After all, the prospect of gazing at the wonders of Tibetan scenery with a long string of plastic sticking out of my nose might undermine the romance of the journey. Later, after settling in again, I peer through the window at the mountain shadows of the lengthening twilight. With the clickety-clack of the train, the effect is mesmerizing.

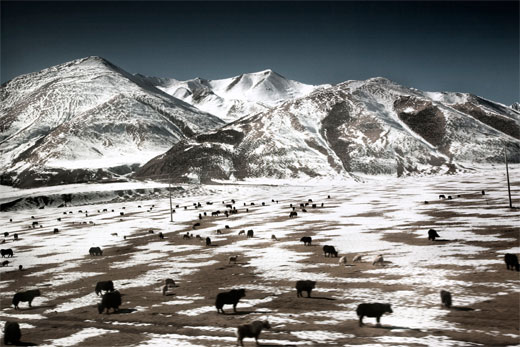

On the third morning, I wake early. The compartment is cold. I peek through the curtains and see a gibbous moon illuminating the landscape. Clouds hang low over the dark, barren and deserted countryside of Qinghai Province, and a distant lake shimmers in the moonglow. The train is slowly pulling up the incline from the southern edge of the great Qaidam Basin, and at full light we arrive at Golmud Station. The 700-mile stretch of track from Golmud to Lhasa is the engineering jewel in China’s iron crown of railroads. For years, a line across the Tibetan Plateau was deemed physically impossible and economically unjustifiable. Eighty per cent of this route is higher than 12,000 feet and the surface is mainly unstable permafrost. But, against the odds, the Chinese authorities launched the project in 2001, and after five years of toil, the highest railway line in the world opened for service at an estimated cost of $3 billion. In addition to the delicate laying of track, the line crosses 675 bridges and runs through the world’s highest tunnel, the 12,000ft-long Fenghuoshan (“Wind Volcano”) Tunnel. Even then, the maintenance of heaving track and shifting pylons plagued the line’s first years, although the authorities now assert that the problems have been resolved and the route is perfectly safe. The train creeps out of Golmud and begins the gradual climb to the roof of the world. At the outset, we chug through a grey, gritty landscape that is almost lunar. Once on to the high, undulating plateau, however, a green hue of sparse grassland washes over the countryside, which contains small ponds and depressions streaked with white salt deposits. The peaks of the Tanggula Mountains to the east snag puffs of cotton clouds, and there is snow in the Bayan Har range to the west.

The train passes several antelope, and near a bend in the track I spot my first shaggy yak standing insouciantly on the crest of a ridge. Hugging the shoulder of a hillside, we cross the Tanggula Pass at 16,640 feet and then start the long, gradual descent to Lhasa. There are many good reasons to take the train to Tibet, but three stand out. First, a train is still the best way to travel in a foreign land. On this trip, you pass through postcard after postcard of stunning scenery, which pile up in your memory. Second, and more practically, the slow ride up to the highlands of Tibet gives your body a chance to adjust by degrees to the altitude. This is a serious consideration, for mountain sickness can quickly lay you low and ruin your adventure. And, third, this is Tibet, and traveling there by train allows you to fix the place in the map of your mind. The mystery and magic of this remote land on the roof of the world deserves a gradual approach, a long, anticipatory overture before the curtain rises. One doesn’t simply drop in on Shangri-La. We roll down the long incline toward Lhasa. The valley narrows as the train picks its way through the snowy Nyainqentanglha Mountains.

Near Damxung we pass our first glacier, a field of white glass squeezed between two peaks. Below 14,000 feet, the scattered tents of nomadic shepherds sprout up like big flowers, and herds of domesticated yaks graze in the permafrost. And now we begin to see isolated Buddhist religious monuments – stupas – on the hillsides and the colorful prayer flags which festoon this intensely religious country. Every peak, point and promontory seems to possess a spiritual significance. The train crosses numerous streams and rivers; Tibet is the fountainhead of Asia and the source of the Brahmaputra, Yangtse, Indus, Ganges, Yellow, Mekong and Salween Rivers. In the villages of Lhasa’s hinterland the houses of brick or stone are unexpectedly substantial. Doors are decorated with strapwork and little ruffled aprons flutter above the windows. Each corner is surmounted by a castle-like turret with a prayer flag on top, and each flat roofline is broken by a big, beehive-shaped incense burner. In the swept courtyards there are stacks of dried yak dung for winter fuel. With one final effort, our weary locomotive pulls the train across the Kyichu River and the track then swings into Lhasa. Rising above the city like a red-and-white mountain is the magnificent, monumental Potola Palace, the 1,000-room residence of the long-exiled Dalai Lama. The train stops. A Tibetan guide meets me outside the new station and drapes a white khada around my neck in greeting. I have been delivered to the top of the world.

Raymond Seitz was the US ambassador to Great Britain, 1991-1994

Photographs courtesy of VII

Your address: The St. Regis Beijing; The St. Regis Lhasa Resort

The first time I crossed the border into Turkey, I was on foot, on a long walk from Gdansk in Poland. My final destination was the glorious city of Istanbul, but on reaching Erdine I found it hard to leave. Right on the border with Greece and Bulgaria, the ancient city founded by the emperor Hadrian was for a while held by Greek troops thanks to some sharp military maneuvering before the outbreak of World War I, and known as Adrianople. The Turks won it back, but it was destined thereafter to be an outlier, a city on the road to nowhere; and that, to be honest, is why I love it so. For me it is the soul of Turkey – and a perfect preparation for Istanbul itself.

After our journey by foot through the grey, drab cities of post-Communist Eastern Europe, Erdine was also a gateway to the marvels of Turkish enterprise: food stalls and coffee kiosks, restaurants and bazaars, and spicy food and minty tea; a cornucopia of possibilities. On our first day, we found a room in an old hotel, with doorknobs polished by a century of use, and woke to the sound of a cockerel crowing like a muezzin. For breakfast we ate yogurt and honeycomb, and went out to explore the second capital of the Ottoman Empire.

There aren’t many tourists in Edirne. As we wandered through its charming Ottoman district, with its collections of 19th-century wooden houses, if we half-closed our eyes we could be back in the world of pashas and viziers, and splendidly accoutred armies on the move to conquer Europe.

The next day, entering the courtyard of the great Selimiye Mosque, we stood before what is, perhaps, the most perfect and ambitious mosque ever raised in Turkey. It is the masterpiece of that 16th-century architect of genius, Sinan, rival not only to the glorious mosques of Istanbul but to the mother of them all, the great church-cum-mosque of Aya Sofya – of which more later. Aside from a few weekday worshippers, I had the place to myself, a moment to reflect on my smallness in the grand arch of the cosmos. A few moments later, I was in the 16th-century hammam, or baths, also built by Sinan, enjoying a leisurely steam soak.

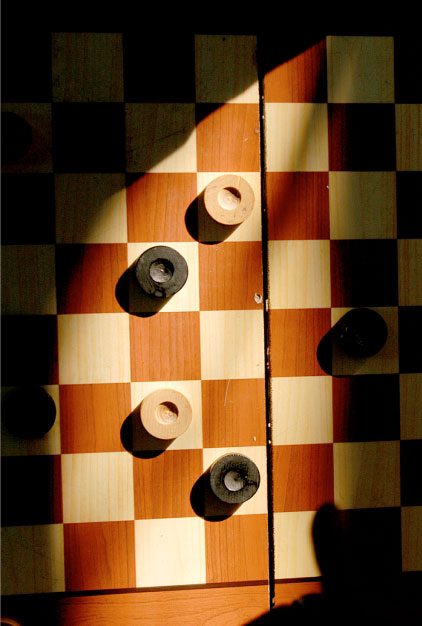

Partly European, partly Islamic, Edirne is comfortably modern yet steeped in the traditions of the past, and above all slow, expansive and relaxed. Life doesn’t bustle in Edirne. Old men play backgammon in the square, and drink their tea. Once, it’s true, the Ottoman armies would gather here to begin their campaigns into Serbia and Greece, even to the walls of Vienna, 1,000 miles away. But with the departure of the armies, the place would revert to its usual unruffled calm, and sultans would descend to hunt in the royal parks, away from the pressures of populous Istanbul.

It’s worth paying a visit here to the Ottoman medical museum, close to the railway station, which recalls the sensitivity of early Islamic medicine, with its particular care for the sick in mind. While Europeans locked their madmen in bedlams, to be jeered and stared at, the Ottoman doctors used gentle and effective treatments – aromatherapy, music and the sounds of water – that could alleviate, if not cure, a patient’s condition.

Some of the city’s cobbled streets, not to mention the odd café, have an almost Central European air. Edirne was linked to Central Europe by trade and war, and many of the languages of Southeastern Europe were once spoken there: Greek and Bulgarian, Serbian and German, and all the mountain dialects of the Pindus and Rhodopes mountain ranges. Edirne is a little lost vision of what once was, and I like it for that. It’s also a taste of things to come.

For what comes next – a few hours away by bus or car – is Istanbul, a city of such grandeur and complexity, a city so freighted with meaning and possibility, rich, bewildering and exciting, that it cannot be comprehended all at once.

Our journey to get there was unremarkable: two days’ walk across the hot Thracian plains, trying to find byways that avoided the main road, and its hum of dusty trucks. Our reward was the sea at Tekirdag, our first sight of the sea for many months, and thousands of miles. We lay on the sand, in the shadow of a minaret, hearing the muezzin’s call to prayer echo across the water and watching a sky crowded with migrating storks. Men in tea shops waved and invited us to join them, but we only smiled. A few more miles, a few more hours, and we would reach the city of our dreams.

“You walked? From Poland?” The reception clerk shook his head. “You must have been carrying a Kalashnikov.” I’m glad he said so: it made me feel rather brave. It was nonsense, of course: all the way from Poland we had been fed and hosted by kindly souls in villages and farms, and when I once brandished a stick it was only to repel a Carpathian sheepdog. But his remark was of a piece with something we had already learnt. “You’re in good hands here,” people always said, as they invited us across their threshold. “But don’t go on. Stop here.” Over the ridge, beyond the river, or in the next town, they said, “They’ll rob you, cheat you, or eat you alive.” And in the next place, of course, they’d say the same.

Along the shore of the Sea of Marmara, where the great ships wait like patient cattle in the roadstead, we had walked, still dreaming, through the stripy walls of the old city of Istanbul – double walls, triple walls, of rubble and stone and bands of brick, punctuated by towers, most fearsome on the landward side. No one, the Byzantines believed, could take the city from the sea. In the shadow of the massive stones, we passed small market gardens that once fed the mightiest city in medieval Europe, with a population of well over a million.

Constantinople, as the rechristened city of Byzantium became known, was founded by Constantine the Great in 330AD to be the second Rome, and much has been made of the fact that it encompassed seven hills, as did Rome. We failed utterly to identify them: Istanbul is simply a hilly city, full of steep streets and even stepped streets, though none rival the splendid Camondo Stairs completed in Art Nouveau glory in the late 19th century.

As we tramped into the city, our belongings on our backs, we passed some of the hamals, or porters, who carry vast loads on their backs secured by a band around their foreheads. Bent almost double, they put our chafing shoulders to shame. But the hills kept us cool, encouraging a breeze, and giving glimpses, from the top of an alley, or a window over the street, of the extraordinary Bosphorus, twinkling and choppy in the summer sun.

Still to this day one of the busiest waterways in the world, the Bosphorus meanders through the very heart of Istanbul, and it puts the city on one of the most astonishing crossroads in the world. Too many cities are known as the place where East meets West; in Istanbul, as we soon discovered, it’s no idle boast. We stood at the very edge of Europe, looking east across the straits to Asia, and the Turkish heartland. Perhaps, as one overawed ambassador put it in the 16th century, it is a city devised to be the capital of the whole world.

His 16th-century world was smaller, of course. But Istanbul felt immediately like the turnstile of a world, whose size we could measure through a few hours at lunch beneath the Galata Bridge, dining on fish plucked from the waters at our feet: the exquisite lüfer, or bluefish, simply grilled. From there we watched the ships that glide along the Bosphorus West to East, and East to West.

The Bosphorus is not a river but a flooded chasm, created thousands of years ago when the Black Sea burst into the Mediterranean, almost a mile wide and several hundred feet deep. Jason and the Argonauts passed by here, and Xenephon’s shattered army of ancient Greeks, and even now it is where the people and the products of Southern Europe meet the Eastern world of the steppe and the far shores of the Black Sea. Oil tankers, Russian warships, battered freighters from China, cruise ships from Naples and Southampton, all file through the straits, dwarfed by the hills of Istanbul, and sliding easily beneath the great suspension bridges that have been flung across from the European to the Asian shore.

Wherever I walked in the city, I found myself knee-deep in history; the past guiding my steps, and its relics scraping my shins. Wandering towards the Grand Bazaar up Divan Yolu – the old Imperial Road from Constantinople to Rome – I trod in the footsteps of Byzantine emperors. Dropping down from Topkapi to Eminonu, I ambled along the road that wound past the Sublime Porte, the seat of Ottoman government, where the Grand Vizier governed, in a sultan’s name, an empire that stretched from the borders of Iraq to the river Nile, and from the Crimea to the Danube. On my way to the Aya Sofya I stopped at the Milion, now just an obscure stump of stone, from where, more than a thousand years ago, all distances within the Roman Empire were measured.

Before actually going into the fabled church-cum-mosque, we descended, via a dark stairway, into the astonishing Yerebatan cistern. This subterranean forest of beautiful marble columns, rising from a shallow underground lake, was built by the emperor Justinian, as was the Aya Sofya just beyond. This was constructed to be the temple to beat all temples and it is said that when, in 535AD, the emperor first entered the building, he murmured, “Solomon, I have outdone thee!”

Aya Sofya’s architects were the first in history to figure out a way of placing a vast dome, with a circular rim, on a building that was essentially square. Square on the earth, for the world below, and domed above, for the divine world. “We knew not whether we were on Earth or in heaven,” a group of 9th-century Russians declared when their Byzantine hosts ushered them into the building – and adopted Christianity on the spot.

It was, it is true, also a piece of imperial bling: I couldn’t help smiling when I saw, at the top of every column, the initials of Justinian and his saucy wife, Theodora, entwined in marble: I and T. And upstairs, in one of the galleries, I was startled to find a marble inscription on the floor that read, simply, Enrico Dandolo: the tomb of the blind nonagenarian Doge of Venice who, in 1204, masterminded the first successful assault on the walls of Constantinople in almost a thousand years. For the great empire of Byzantium, which ruled from this city, it was the beginning of the end.

The city that lies before our eyes is now primarily Ottoman. When their great armies stormed the city for a second time in 1453, raised the crescent of Islam over the dome of Aya Sofya and made the city the capital of their new empire, they set about restoring its glory. Successive sultans indulged in a frenzy of building, paid for by the trade and peace they brought to Istanbul. Great new mosques decorated the skyline. At their feet, the famous Grand Bazaar dropped down the hillside to the Golden Horn, a huge creek.

I always enjoy visiting the bazaar, the original shopping mall, a glorious warren of tunnels and arcades offering everything from old books to jewels, where you can always find a pleasant café and sit for a moment drinking in the atmosphere. The Grand Bazaar has two mosques, more than 5,000 shops and innumerable secrets, and perhaps no one in Istanbul really knows them all.

The streets around are worth exploring, too, not least for the amazing old caravanserais, where caravans of camels from the Asian side or of mule-trains from Europe would be stabled, and their goods unloaded and stored, while the merchants haggled and ate and slept upstairs.

Nor should the sultan’s palace be missed. Unlike Versailles or Buckingham Palace, Topkapi is not a monolithic building with a façade designed to make you feel small, but more like a luxurious encampment, a sequence of pavilions and tents raised in marble and stone, spilling down the hill of Seraglio Point to the Bosphorus below. It is formed of three increasingly intimate, and secure, courts: the first public, and the last for the enjoyment of the sultan and his family alone. To one side are the harem apartments, built and rebuilt over the centuries to house the sultan’s many concubines and women attendants. Walking through, it charms and outrages in likely equal measure.

Looking out from the palace are views of a conical tower across the waterway known as the Golden Horn. Not as majestic as the Bosphorus, into which it flows, the Golden Horn is a substantial creek, and it divides old Istanbul from the district known nowadays as Beyoglu, which leads on to other, more modern districts of the city. Once known as Galata, it was originally a small walled city of its own, run by Italian merchants; over the centuries it has kept its European character, and today it is where the consulates and the restaurants, the bars and many of the hotels of Istanbul are found. The area around Topkapi, Aya Sofya and the Blue Mosque is good for sightseeing, but Beyoglu is where modern Istanbul hangs out.

Indeed, below the heights of Galata, below the famous Genoese tower (worth a lift to the top, for the stunning views), is Istanbul Modern, a former brutalist warehouse converted into a smart contemporary art gallery. One moment, then, you are in an arcade of the Grand Bazaar, in a café out of the Arabian Nights, and the next you find yourself in an achingly cool diner straight from New York or San Francisco. Such is Istanbul.

Whenever I return – which I have done, almost annually, for the past 20 years – I find myself standing in mute astonishment at the sight of a city caught so dramatically between the continents, between the ages and the faiths, between the ancient and modern. I see first-timers stepping out, wary and expectant, clutching their guidebook, wondering which way to go, and envy their discovery.

The Baklava Club by Jason Goodwin, an Inspector Yashim mystery, is published by Sarah Crichton Books

Your address: The St. Regis Istanbul

Images by Gallery Stock, Getty Images, Franco Pagetti/VII, Ashley/VII, Serrano Anna/Hermis.fr

“I was an army brat and traveled all over the world with my father to places like Burma,” the 48-year-old says. “Wherever we went we’d take at least 25 trunks. To me, that was how people traveled.”

When the designer joined Moynat in 2011 from Hermès, where he’d worked for ten years under Martin Margiela and Jean Paul Gaultier, the LVMH accessories brand offered the perfect link between private passion and professional career: Nair owns more than 200 antique trunks. Moynat, which was launched in 1849 by Pauline Moynat, who sold travel goods, and trunk-making brothers Octavie and François Coulembier, was one of France’s oldest trunk-makers, with a reputation for innovation. “In 1870, it brought out a lightweight trunk using a wicker frame instead of a metallic one,” Nair explains. It was also, he adds, the first to use hardened gutta-percha waterproofing as well as varnished canvas and leather trimming.

What appeals most to Nair, though, is the manner in which trunks were customized. “There were all sorts of styles made,” he explains. “The limousine style was curved to fit on to a car roof; the cabin trunk opened in front and slid under the berth; while automobile trunks attached to the back of the car, before the trunk as we know it today was devised.”

The first trunk Nair ever bought, in Chantilly in France, was “a real fluke”, he admits. Although it was in fantastic condition, its owner was desperate to get rid of it. “Because it was arched, she couldn’t use it as a table and it was just gathering dust in the garage,” he says. “So I got it for only around $270.” A contemporary Moynat trunk, on the other hand, will set you back several thousand dollars.

Other unexpected finds have been a 1907 cabin trunk from Marseilles, with its key still in the lock, and an ugly black trunk found in Rennes. “After stripping and cleaning it, it turned out to be a lovely dark green, which, I then discovered, matched the car that it was originally designed for.”

“I am fascinated by the idea of the customer asking for a certain color and a certain number of locks, and the reason they wanted them,” he continues. “I always wonder what adventure they were going to have.”

His favorite models are those from the Belle Epoque, which he describes as “real couture pieces, because no trunk is similar to another”. But these are becoming increasingly difficult to find. “I have contacts all over Europe – France and England are the best sources. But really lovely ones are becoming a rarity, which makes the ones I already have even more precious.”

You see them all over the world, jogging, hiking, paddling, surfing and mountain climbing. And no, we’re not talking about athletes here. We’re talking grandparents. The generation once known as the “blue rinse set” is now not only active, but affluent. And there is nothing they like more than to spend their reserves of leisure time, money and energy than with their extended family.

According to the National Leisure Travel Monitor, more than a third of all grandparents have been on vacation with their grandchildren. And children are

all for it. A study by the marketing firm Ypartnership confirms that 60 per cent

of children between the ages of six and 17 said they would like to travel with

their grandparents – and some even said they would prefer to leave their parents

at home.

As a result, travel agencies such as Boston-based Road Scholar now offer extensive holiday options for multigenerational families, including special programs that cater only to grandparents and their grandchildren. At the top of the list, they say, are hiking holidays in the National Parks. “Our clients want to hike, surf, bike and balloon in places like Arizona and Utah,” says manager Andre Purdy. European trips and cruises are also popular, he says, particularly those offering excursions that allow the younger generation to let off steam on land, while their grandparents relax on board.

The trend for multigenerational travel is yet another by-product of ageing baby boomers, says international travel brand consultant Sarah Miller. “The greatest luxury is time well spent,” she says. “Grandparents might have a wonderful memory from the holiday, but the hotels need the grandchildren to remember it too, so that when they grow up, they want to recreate something similar with their own family.”

Which is why hotels all over the world are rapidly adjusting to the trend. “Instead of having just rooms, hotels now have villas which an entire extended family might share,” says Miller. “They are also pushing their footprints beyond their own walls and into the city, by offering shopping excursions, gastronomic tours, cooking classes and art classes.” St. Regis has been at the forefront of this trend with its Family Traditions at St. Regis program. Large hotels in exotic locations that offer a mix of culture, activities and relaxation – as The St. Regis Abu Dhabi does – are particularly popular with groups whose ages vary. “While one member of a family may feel energetic and go on an excursion, another might want to enjoy time at the beach,” says Laila Rihawi, the hotel’s public relations manager. “There may be one day where they go on an excursion together, say to the Empty Quarter and the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque. But the next the grandkids and grandparents might go on their own to Yas Island’s water park and Ferrari World, or go on a Big Bus Tour.”

The three-bedroomed Abu Dhabi Super Suite, with staff quarters and a 14-seat dining room, is often booked by extended families, many of whom travel with nannies. Favorite destinations include places that sleep large groups and have spaces set aside for large-scale parties or entertainment, says Deborah Bigley, a specialist in organizing big group and multi-activity vacations. “Spaces need to be big enough for everyone to have their own independence and yet still be able to come together for dinners, which might be prepared by a chef one night, and on another by the families themselves.”

Helene Lorentzen, a Palm Beach-based consultant and mother of three boys, says that exotic destinations are popular, too. Last year, she brought together her extended family on an island in south-east Asia. “We all had our own enormous rooms, which were very private, as well as a big area where we could all gather. Because the staff were amazing, too, we never had to worry about logistics.”

Her mother – in her eighties – not only enjoyed the reunion, but joined in on all the activities. “Every one of us went for a surfing lesson – and nothing makes a grandson prouder than a surfing grandmother, even if all she did was ride the wave lying down,” says Lorentzen. “And a morning trek was organized for us though the rice paddies to a remote lunch spot, where my sister got engaged.” Although the aim of many vacations is just to bring together families, a large number are organized to celebrate a specific milestone. According to the

Travel Industry Association of America, more than three-quarters of travellers

have planned a vacation around a celebration such as a birthday, anniversary

and wedding.

Marie Divine, a New York-based mother of three, recently returned from a multigenerational visit to Vietnam. “The purpose was to return to the country where I was born [Divine was a diplomat’s daughter] with my husband and children – and then we thought, why not ask my [widowed] mother along as it was an important place in her life, too.” Divine planned the entire two-week trip with great precision. “When you have all age groups, you have to plan carefully, especially if you’re moving around,” she says. She mapped a daily list of activities that catered to all age groups, and hired a minivan to ferry everyone around. “This was a critical plus. Though we were moving around, we always settled back into the minivan and chatted about what we just experienced,” she says.

More than anything, it is these chats, she believes, that will always be remembered by her children. “Unlike other family occasions I have been to, like big celebration lunches, a trip is very different. It’s an activity that can be shared, and unlike golf or tennis or skiing which require stamina, all you have to be is present to take part.” And a trip, she adds, is a wonderful time for generations to get to know each other again more intimately – and learn more about their family history. “In our very anonymous world we are increasingly fascinated by our own families and their mythology. And kids no longer think that adults are square – partly because we all do and share so much.”

Her advice to anyone thinking of a similar adventure is to consider pace. “Some people move faster than others. A 15-year-old might decide a morning of sightseeing is enough, and need afternoons off. People should be able to drop out of an activity without feeling they are letting anyone down.” I know from experience that children really do savor these experiences. My 19-year-old son Ivan, now a college freshman, remembers a holiday we took with my parents eight years ago to Bermuda (the year before my mother died) with great affection. “There’s a short window in a kid’s life when he or she doesn’t realize he is different from his mother. He just thinks he’s just another part of this person

that laughs and summons food from nowhere and is warm,” he says. “The family holiday, when it goes right, restores that period. While a lone holiday can

provide a masculine re-affirmation, and a couples’ holiday can be passionate,

an inter-generational holiday is incredibly calming. Leaving your everyday circumstances and returning to the family fold can trick you into thinking you’re

a blissful baby.”

1. The Soviet Union, 1986

This was my first overseas trip. I’d been saving my babysitting money for five years, and found an anti-nuclear war organisation that took students to Moscow and Leningrad. Although it was controlled and pretty grim – there was nothing to buy, and it was a gray November – we did get to talk to Russian teenagers and professors. One asked if we could name any Russian cities other than Leningrad or Moscow, or any living Russian authors. And we couldn’t. I discovered then that you could learn about places without going there. When I got home I enrolled in Russian and International Relations college courses. That was a mistake: it was like marrying the first boy you ever kissed. I wasn’t in love with Russia; I was in love with travel.

2. Wyoming, 1992

After college I did a road trip with my then boyfriend to the Rocky Mountains. It was so exotic; after Connecticut, where I grew up, Wyoming was the real Wild West. People had guns. My job as trail cook was to take up to ten people into the mountains on horses, hunting and fishing and exploring glacial lakes. I had no experience, but I had more capacity than I thought. And my first story was based on those experiences, and launched my career as a writer.

3. Texas, 1994

I’d heard about these rodeo groupies called Buckle Bunnies, and so pitched an idea to an editor about doing a piece on them. It was my first paid assignment and the pressure was huge. I had to learn to walk up to strangers and get them to tell me about their lives; in this case, their sex lives. I learnt something I have used ever since: if you are straight with people, tell them what you’ve come for and what your boss expects from you, and confess to your stupidity, they’ll often tell you what you want. I learnt then I could be a journalist.

4. China, 1998

At that time, journalists weren’t allowed into China. But I was naive and cocky. I said on my visa form that I was a housewife and bribed people to take me to the Three Gorges Dam, so I could write a story. It was only on the plane on the way back that I realized how stupid I had been. I knew then I didn’t have the stomach for hardcore reporting. Sometimes you have to make a journey to realize you’re on the wrong journey.

5. New Zealand, 2000

This time I thought: forget about global politics, let’s do something fun. So I went on a research vessel with scientists off the coast of New Zealand to go in search of giant squid. Although looking for a sea monster was exciting, on the ship I realized that I could not have children and that I did not want to be married to the person I was married to. The results of that personal journey were so devastating that I didn’t go traveling for quite a while.

6. India, 2004

When I went to an ashram in India, I was at a real crossroads. It was a point at which I changed enormously: there was me pre-India, and there was me after-India. I stayed in the same ashram for four months, and the greatest lesson I learnt was to be still. It wasn’t fun, but it was a great spiritual journey. There are many reasons to travel: to have adventure or to run away or to be exotic or to learn about another culture. Sometimes only a pilgrimage can help you find out about yourself.

7. French Polynesia, 2012

This last journey was glorious: traveling around islands to do research for my most recent novel, The Signature of All Things. Up a volcano, in the rain, on a remote island, I suddenly realized, at the age of 43, that I was exactly where I wanted to be in my life: collecting fascinating pieces of information to write up. It’s a great position to be in. The quote I love is, “It is better to live your own destiny imperfectly than to live a perfect imitation of someone else’s life.” In 2000, when I was married, I wasn’t. So it’s gratifying to see I’ve learnt those lessons.

The Signature of All Things is published in paperback by Penguin

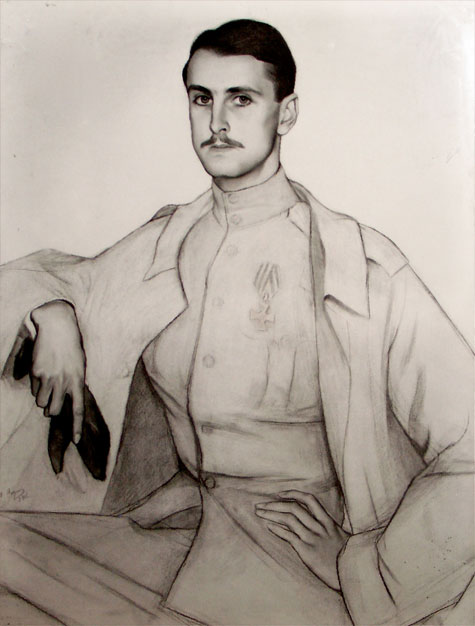

Serge Obolensky’s life reads like a work of fiction. There is a fairy-tale beginning: he was born a Russian prince and married a princess. There is adventure: for our prince was brave as well as handsome… a dashing young cavalry officer in the First World War, he escaped from the Bolsheviks with a price on his head, while in the Second World War he became an American commando who parachuted into Nazi-occupied Europe. There is Gatsby-era glamor: the second Princess Obolensky was a renowned American heiress. And a dash of cocktail lore: legend has it that he inspired the creation of the Bloody Mary in the King Cole Bar of The St. Regis New York. This heady concoction sounds too extraordinary to be true, but life can be stranger than fiction, as Obolensky well knew.

Let us begin, though, at the beginning, in 1890, when Serge Obolensky was born, the heir to one of Russia’s grandest aristocratic families. Decades later, in his memoirs, he recalled the vanished country of his youth: the winter sleigh-rides to his grandmother’s palace in St. Petersburg, the summers spent on his parents’ vast estates, the fun of Countess Tolstoy’s costume ball. And there were trips abroad, for like other wealthy Russians, the Obolenskys travelled widely – visiting Paris, or fashionable belle époque resorts such as San Sebastian and Biarritz.

Obolensky’s education was rounded off at Oxford, England, where he played polo and joined the exclusive Bullingdon Club, while out of term he was a hit with London’s leading hostesses. Many of the friendships that Obolensky formed at this time would be important in his later life.But in both London and St. Petersburg, he was experiencing two great imperial capitals on the eve of enormous change. In London he recalled “an air of massive elegance and leisure all but inconceivable in any later period. I believe I saw the end of it… the mellow grandeur of the Edwardian age.” In Russia, revolution was about to bring the Obolenskys’ world crashing around them.

Obolensky called his memoirs One Man in His Time, but what is remarkable is his knack of being in the right place, if not at the right time, then at a fascinating time. Even with the advent of war, when he joined the crack Chevalier Guards regiment, he enjoyed one final “cavalryman’s paradise”, as his regiment covered the Russian army’s slow retreat in “a form of warfare that will never come again”, as the age-old hegemony of mounted soldiery gave way to an era of trenches and tanks.

If Obolensky’s recollections make the war seem almost fun – more fun than the trenches, certainly – it is worth noting that he also won the St. Andrew’s Cross for valor three times. Meanwhile, like many of his class, he sensed the coming crisis as the vast Empire of all Russias began to fracture under the strain of war. In 1916 he married Princess Catherine Yurievskaya, the daughter of Tsar Alexander II and his aristocratic mistress (and later wife). Catherine had grown up in France and wasn’t close to the current Tsar, Nicholas II; nor was Serge. Yet their lives, like that of millions of Russians, would be turned upside down when Nicholas led the Romanov dynasty and the nation into the abyss.

With the onset of the Revolution, the big cities were plunged into chaos, and Serge and Catherine joined an aristocratic exodus south to the Crimea, that Riviera-like coastline of palaces and villas he’d known well as a child. There he joined the “White” forces fighting the Bolshevik “Reds”, but as the horrors of civil war unfolded, even a battle-hardened Obolensky found the mix of horror and beauty “sickening... the total destruction of a childhood memory”.

Around this time the society painter Savely Sorine drew a sketch of Obolensky, capturing something serious about the eyes as well as the elegance of the young officer. This portrait would eventually wind up in Obolensky’s apartment in Manhattan, where in 1970 he was photographed alongside it for a New York Times feature headlined: “Serge Obolensky: a Society Legend at 80”. All those years later, he is recognizably the same man. But just like its subject, the sketch had gone through some dramas along the way. It acquired a spray of bullet holes when the Reds shot up Catherine’s palace in Yalta. Then it was displayed with the inscription, “Serge Obolensky, Wanted, Dead or Alive”, until Sorine bribed a guard with three roubles to let him take down the sketch and then smuggled it out of Russia. More importantly, the artist also spirited Catherine out of her ransacked palace and into hiding. Husband and wife would be reunited in Moscow, both in disguise, having endured hardship and danger. They eventually escaped to London, via Vienna and then Bern, where Serge could access the $200,000 he had cunningly squirreled out of Russia into Swiss bank accounts.

A tiny fraction of the Obolensky fortune, this was still considerably more than many exiles managed to escape with. During the 1920s former Russian debutantes worked as cabaret dancers in Shanghai, while one Romanov prince eked out a living as a Paris taxi driver. Many White Russians never quite got their heads around these reversals of fortune, their grief at what had been left behind or the sorrow of exile. Presumably Serge Obolensky felt all of the above keenly. But just as impressive as his derring-do flight from Russia was his ability to shed any Russian might-have-beens and get on with his life. “He never looked back,” his son Ivan Obolensky agrees. “He had a resilience, an ability to hang on to happy memories, but always to look forward.”

Serge’s father had intended him to be a modern agriculturalist farming the vast family estates. Now the estates were gone. What remained, however, was Obolensky’s extraordinary charm, surely key to his remarkable ability to land on his feet. People liked Serge Obolensky. This had probably saved his life in Russia, where he had been aided by a former employee, an old shoemaker of his acquaintance, and a nurse he’d never met before, all at considerable risk to their own lives. This quality would serve him well throughout his life. “He had such ease,” his son recalls, while his secretary told the New York Times, “He could charm the birds from the trees.” And looking at the photographs of him whirling celebrated beauties around the dance-floor, it is clear that women adored Serge Obolensky. And he certainly married well – as princes in stories are meant to.

On escaping Russia, Serge and Catherine lived increasingly separate lives and then divorced, amicably. Serge moved into the flat of his cousin, Prince Felix Yusapov (famous as one of the men who murdered Rasputin) in London’s Knightsbridge, and then after an ill-starred trip selling farming equipment in Australia, settled down to the prosperous, bowler-hatted life of the London stockbroker. Then one night he went to a costume ball and danced with Alice Astor. He was dressed as a Cossack. She was wearing a Chinese dress and a necklace from the tomb of Tutankhamun. They promptly fell in love.

Alice’s father, John Jacob Astor IV – one of the richest men in America – had built New York’s celebrated St. Regis Hotel. He went down with the Titanic, but Alice’s mother Ava, the formidable Lady Ribblesdale, was very much alive and strongly opposed to her daughter marrying “an impoverished Russian prince”. However, when Alice came of age, she got her way, and their marriage was the wedding of the London Season in 1924. Or rather weddings, for there were three: an Anglican one at the Savoy Chapel, a civil ceremony, and then an Orthodox one at the Russian Church. Alice’s British cousin, Viscount Astor, gave away the bride, while Serge’s old Oxford friend Prince Paul of Serbia was best man. They honeymooned in Deauville, France, and thus began their luxe, but peripatetic, married life spent on ocean liners and yachts, in grand hotels or at their spectacular homes in London and upstate New York.

“Nothing world-shaking happened – which was pleasant for a change,” Obolensky quipped of this time. Looking back, their decade together was “a haze of golden memories... I enjoyed it enormously.” But one senses a quickening of the pulse when, after Alice filed for divorce in 1932, Obolensky started working in earnest for her brother, Vincent Astor, who tasked him with restoring the luster of The St. Regis New York, which had just returned to family ownership. “Vincent suggested that I look things over and make my suggestions,” he explained, “as I had lived much of my life in the best hotels of Europe. He made me a sort of general consultant, promotion man, and trouble-shooter… This is how I started in the hotel business. I found it captivating and a challenge.”

Obolensky turned out to have a genius for hotel-keeping. When Obolensky took over The St. Regis, he says, “the old-fashioned lobbies were dark and uninviting. There were no wine cellars, and the food was conventional. Yet the building was an architectural masterpiece. When Colonel John Jacob Astor IV had built it, he’d wanted to make it the great luxury hotel of the New World.” Working with the decorator Anne “Nanny” Tiffany (and “various impoverished but brilliant Russians”, as Ivan Obolensky recalls) Serge and Vincent set about updating the public areas. The roof garden soon became a “Viennese fête champêtre”; a rink was installed for ice shows; and the hotel acquired a Russian-themed nightclub, the Maisonette Russe, complete with a gypsy orchestra and a chef who had cooked for the Tsar. (He was a friend of Vassily, the Obolensky family chef who’d escaped Russia with Serge.) Most notably, the Maxfield Parrish painting of Old King Cole (from another old Astor property, the Knickerbocker Hotel) became the centerpiece of the new bar. It was here, as legend has it, that Obolensky made his contribution to the creation of the Bloody Mary. The story goes that he asked barman Fernand Petiot to spice up his tomato and vodka cocktail – thus introducing the dash of Tabasco.

But Obolensky’s strategy went way beyond hotting up the cocktails and refreshing the décor. A great metropolitan hotel is part of the swim and flow of a city. Serge knew this instinctively, and he knew how to deliver it – by inviting his fancy friends around. Time and again the society pages of the era contain an item headlined “Prince Obolensky hosts” – usually describing a dinner for a Vanderbilt, a Whitney or visiting European royalty. Obolensky was clearly very social, but these meticulously placed stories also show a hotel man hard at work promoting his hotel. And if all this was a formula, then it was one that worked well for Obolensky, keeping our hero gainfully employed for decades.

“Serge Obolensky abhors a vacuum,” teased one nightclub reviewer in 1959, as he’d transformed a hotel basement into “another of his imperial fashion bazaars. Colonel Obolensky has an eye for grandeur, réclame, décor and White Russian nights of gala. So he can be forgiven for not having an ear for dance music.” Harsh, perhaps, as Obolensky loved to dance, although maybe a man introduced to nightlife in pre-Revolutionary St. Petersburg might struggle slightly with the advent of rock’n’roll.

In other ways, however, he was a modernizer, and as such the recipient of criticism from the kind of hotel guest who never likes change. The New Yorker magazine once ran a piece, a classic of its kind, interviewing a woman called Clara Bell Walsh who’d occupied the same hotel suite for 43 years. “They don’t have this sort of thing today,” she’d told the reporter, pointing to the original furnishings she’d retained in her room. “The Russians have kind of colored this place up too much to suit me,” she complained. “What, the Communists?” the bemused journalist asked her. “Serge Obolensky!” came her furious reply.

Only war seems to have got in the way of Obolensky’s extraordinary career as a hotelier – and even then, The St. Regis Hotel helped shape this, our hero’s next great adventure. Obolensky, who’d taken American citizenship (and dropped the use of his title) in 1931, was keen to fight for his adopted country. Too old to enlist in the regular army, he joined the State Guard. But the Guard seemed unlikely to see action in Europe, so he asked a friend in the military how he could transfer to the commandos. “That’s easy,” came the reply. “Why don’t you talk to Bill Donovan? He’s staying in your hotel.” Obolensky spoke to “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services, who promptly took him on. And so after commando training which he said “nearly killed” him, Obolensky, by now 53, parachuted into occupied Europe, twice. In both cases, his mix of charm and courage won the day. In the first drop, he landed in Sardinia with just three other men and a letter from General Eisenhower to negotiate the surrender of the Italian forces on the island. Next, he jumped into France to prevent the retreating Germans from blowing up the power station serving Paris. He won over both the Resistance and the commander of the Vichy French. Then the main column of Germans finally surrendered to one Colonel Grell, “our plans officer, who had been my assistant manager at The St. Regis”.

In the 1960s Obolensky returned to the hotel where his career had begun, and in his memoirs discerned common ground between hotel-keeping and soldiering. “Hotels are a human enterprise,” he wrote. “You have to be known and liked by its rank and file, the waiters, the captains, the clerks, the manager – it all adds up to esprit de corps. Despite a good building and a good location, everything depends upon people – on goodwill, good service, and, in a sense, on personal friendships.” In a sense, human relationships lay at the root of the life Obolensky forged for himself in America. As that New York Times profile put it, “though cynics might attribute his success to the drawing power of his title, that would be to underestimate the magnetism of his personality and talent for friendship.” So did he ever feel slightly weary of another night of gala, of “Prince Serge Obolensky hosts”, of singing for his supper? If he did, he never showed it. “I just think that it would be the greatest mistake for an old bastard like me to quit,” he quipped when asked about retirement. At 80 he still did yoga every morning and went out most evenings, “leaving at midnight, without fail”, Ivan Obolensky recalls. “That was his rule.” Around this time, though, he gave up performing the celebrated Russian Dagger Dance. A highlight of New Year’s Eve balls for decades (with proceeds going to the victims of Communism), this involved Obolensky balancing on a rickety table while hurling flaming daggers at targets with a remarkable degree of accuracy.

He also abandoned his bachelor existence to marry for the third and final time to a woman four decades his junior, Marilyn Fraser Wall, from the wealthy suburb of Grosse Pointe, Michigan. And so it was there in 1978 that, some 88 years after it had begun at an Obolensky villa beside the Summer Palace of the Romanovs, this remarkable life drew to a close. Princely proof that life can be stranger than fiction.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Images courtesy of the estate of Ivan Obolensky, Superstock, Illustrated London News Ltd, Mary Evans, Bettman/Corbis, Conde Nast Archives, Corbis, Getty Images, Wire Image, Bert Morgan Arhive/Alamy, Popperfoto/Getty Images

The craft shop in Bangkok by David Yeo

35 Soi 40, Th Charoen Krung, Bangkok

Although most of the shops along this busy, narrow street cater to tourists, this unique store in a former monastery can be found among a cluster of interesting antique shops. Stepping inside Thai Home Industries is like being transported on to a dusty film set back in the days when Somerset Maugham stayed nearby. It’s family-owned –they’ve had it for four generations – and the staff, who all appear to be in their sixties, are laid-back and charming. I don’t think they even have an electronic till; all sales are handwritten on a simple ledger, and their only nod to modern times is a credit-card machine.

One of the things I particularly love is that there seems to have been no thought as to how products are displayed. They are stuffed randomly into whatever space is available, which makes for a very interesting visit because you are never quite sure what is in the next display cabinet, except that it will be whimsical and a delight. In one there might be finely woven rattan fruit baskets and highly polished mother-of-pearl shells; in another, embroidered napkins and hand-beaten wrought-iron platters.

The bronze bowls – or khan long hin – are my favorite. Used to offer gifts in Thai Buddhist rituals, they come from the tiny bronzesmith village of Baan Phu in Thonburi province and are incredibly time-consuming to make. First, raw copper, tin, and a special type of particularly malleable gold are melted together in a charcoal-fired cauldron to create the unique blend of liquified bronze. Once that is set, each piece will be worked and polished by a master craftsman. They are unique not only in Bangkok but in the whole of the country, as are many of the objects at Thai Home Industries.

Your address: The St. Regis Bangkok

A global market in Manhattan by Donna Karan

705 Greenwich Street, New York, urbanzen.com

It’s like a sophisticated global market, every piece selected according to who produces it. There is handmade furniture and pottery from Bali, handcut lace bedlinen from Vietnam, myriad artisanal jewelry made of bead and bone, papier-mâché shopping bags, tobacco-leaf vases…

I’m obsessed with preserving culture through artisanal crafts because they’ve been passed on from generation to generation. And with artisanal pieces you can feel the hand that created it – personal, one-of-a-kind, made just for you. Even when an artisan makes the same pieces, no two are ever identical, so you’re buying something special.

To me, any time you have an artisan make something, you are supporting the artist, their family and, by association, their community. Some projects were set up for specific reasons; for instance, the Urban Zen Haiti Artisan Project was established in conjunction with the Clinton Global Initiative to help create business opportunities for Haitians after the earthquake of 2010.

Another thing I enjoy is the pride with which everyone at Urban Zen works. They’re aware of being a part of something bigger than a typical retail store, that ten per cent of sales goes to support the Urban Zen Foundation – and that there’s a story behind what they’re selling.

I fall in love with the place every time I go in there. It’s so evocative of other cultures, with comfortable furniture to sit on, tribal music playing and the scents of essential oils in the air. It feels like someone’s exotic home. I’m constantly discovering new things, and I have never walked out without a bag in my hand.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

The wine shop in Rome by Olivier Krug

Via dei Prefetti 15, 00186 Rome, enotecalparlamento.com

I discovered the Enoteca al Parlamento about nine years ago, walking with my son, whom I had taken to Rome on his own for his 10th birthday. Walking down a tiny street near the Palazzo Montecitorio, the Italian parliament, right in the heart of the city, we spotted three windows: not big, but filled with beautiful bottles. So we went in, and spent hours there. The owners, a charming man, Daniele Tagliaferri, and his wife, Cinzia Achilli, whose father Gianfranco founded the shop, have built it up to be the best wine shop in Rome. It has got more than 10,000 bottles from all over the world and all sorts of spirits, including cognacs and armagnacs from 1800, which they tell me they would never sell. What was wonderful was that, when we went in, they had dozens of empty bottles of Krug signed by my family, who unbeknownst to me had been there before us, as well as photographs on the wall of our old Krug Rolls-Royce delivery car.

Now whenever I’m in Rome I go back. It’s a great combination of a little restaurant, a delicatessen and a traditional wine shop.

One minute you’re walking in, and hours later you’re struggling out having bought almost everything. The food is incredible. I usually end up having four courses – mostly pasta – and then spend ages deciding what to take away: they have 80-year-old balsamic vinegars, pickled mushrooms, grilled onions, olive oils, honeys and jams. And incredible cheeses. I always leave with mozzarella and parmesan (although I’ve learnt that you can’t take mozzarella in your hand luggage, so now if I’m going to Rome I carry check-in luggage).

Cinzia is also a chocolate specialist, and I usually leave licking my fingers, having been given one of her premier-cru chocolates as a treat. The family have become friends, and now often come to stay just before Christmas, bringing with them a little picnic of treats for us. When we walked into that shop the first time, we never dreamt that would happen.

Your address: The St. Regis Rome

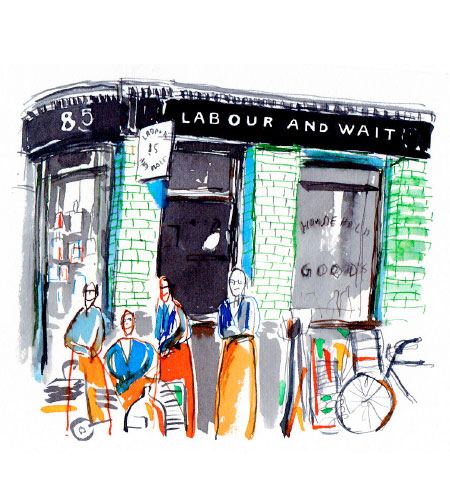

A cool hardware store in London by Bruce Pask

85 Redchurch Street, London, labourandwait.co.uk

Since I started exploring Shoreditch in East London a few years ago, it has undergone a transformation not unlike that of Williamsburg in New York, where an authentic, formerly “textured”, shall we say, neighborhood has become a bit of a scene. Labour and Wait is on the corner of a great street, which has changed almost out of recognition in recent years. The rounded facade is covered in beautiful green glazed tiles which make it look as though it’s been there for many years. The interior feels like a cross between an old hardware store and a design museum: full of utilitarian items and household gadgets carefully curated and beautifully presented.

The staff wear these great work aprons, which lends it the mood of a dry-goods shop from yesteryear. They also maintain a hushed, respectful air, allowing customers to quietly ponder their purchases. I find it all quite relaxing and so contrary to the craziness one finds in most stores these days. When I walk in, time slows down. It inspires a pensiveness, a quiet reverence for beautifully functional, everyday objects that have stood the test of time by being well made and utterly useful.

I often seek out hardware stores when I travel because each country has its own unique everyday objects. The products here are specifically English and although they may seem quite old-fashioned, they are very useful: handmade brushes, pendant lamps, enamel kitchenware and beautiful wooden toilet brushes paired with a slender galvanized bucket. They also carry the loveliest vintage Welsh blankets.