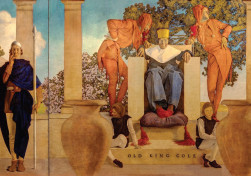

That snowy evening in March 1900, it seemed as if all of New York high society had crowded into the Berkeley Lyceum Theater on West 44th Street. The auditorium, glittering with ladies in pearls and fashionable off-the-shoulder dresses, flourishing lorgnettes and escorted by evening-suited gentlemen, buzzed with excitement. Before them lay an extraordinarily exotic scene: a set painted with blossom-laden cherry trees, wooden and bamboo houses of the legendary Yoshiwara pleasure quarters of Tokyo, a cluster of Japanese actors dressed in outlandish costumes, and in the center, a single, tiny, dainty figure, her head tilted coquettishly. With her stiff brocade kimonos, foot-high wooden clogs and knotted hair studded with tortoiseshell hairpins as long as knitting needles, she was utterly exquisite. As an enigmatic smile flickered across her face, a hush descended on the auditorium. Then, with a flutter of her fan, she began to dance.

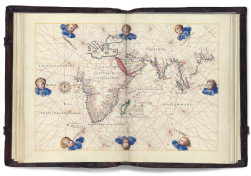

Japan had been open to the West for less than 50 years after centuries of isolation, and almost immediately Westerners had gone mad about its wonderful arts. On both sides of the Atlantic, Japonisme was all the rage. Vases, swords, netsuke, woodblock prints and blue-and-white porcelain were treasured collectables, fashionable ladies wore kimonos as exotic evening dress and Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado had been a smash hit. But while society had heard about the mysterious geisha of Japan, no one had ever seen one. And now suddenly here was Sadayakko: “like a woodblock print come to life”, as one admirer said.

My own journey through 21st-century Japan in search of Sadayakko’s history could not have started farther away from the gilded world in which the geisha lived. Stepping out of the spectacular high-tech steel and glass halls of Kansai International Airport, which floats on an artificial island off the coast, I take the train to Osaka, where (as I always do when I arrive in Japan) I feel as if I’ve been transported into the future. Once a seaport, Osaka has long been the commercial heart of the country, home to merchants famous for their business acumen. Nowadays it’s a city of futuristic skyscrapers crammed side-by-side with ancient temples, quiet parks and tiny tile-roofed shrines guarded by carved stone lions. Neon lights the sky, buildings tower into the clouds, shops gleam with fashionable gadgets. On Midosuji Dori, the so-called Champs-Elysées of the Orient, home to The St. Regis Osaka and lined with sophisticated boutiques, there’s a rush of noise and bustle and crowds. A dozen lanes of traffic hurtle between the gingko trees that shade the sidewalks, hawkers sell roasted chestnuts and people in designer labels, business suits or the occasional kimono hurry to work or sip cappuccinos in the nearby Starbucks. Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Apple are here alongside shops selling gold, kimonos and silk-covered sandals.

It’s hard to imagine that just over 100 years ago, in Sadayakko’s time, the city was a maze of tiny streets, the widest just broad enough for very early motor cars, the back alleys so narrow that not even a rickshaw could squeeze through. It was in 1899 that she had set off with her husband, Otojiro, and a small group of actors, to America: the first professional Japanese theater troupe ever to tour the West. And it was then that her own journey to superstardom had begun: her transformation from a geisha to the most famous Japanese woman of her time, the woman who inspired Puccini’s opera, Madame Butterfly.

In her youth Sadayakko had been Japan’s most famous and desired geisha. From the age of four she was trained in dancing and singing, and she went on to become the mistress of the prime minister, Hirobumi Ito. Geisha were trendsetters and, as well as wearing multi-layered embroidered kimonos, Sadayakko experimented with western bustles, bonnets and high-heeled shoes, rode horses and played billiards.

In spite of being famous in Japan as a geisha, she wasn’t an instant hit when she arrived in America. At first the troupe had planned to perform as they had in Japan, using only male actors. But they realised that to appeal to American audiences they needed a female star. As a geisha, Sadayakko could dance and sing and perform kabuki plays, and she was beautiful. No sooner had she landed in San Francisco than word quickly spread across the country, and a tour was arranged. In Boston she drew record audiences and rave reviews. In Washington, she was asked to dance before President William McKinley. By the time she reached New York, she was a superstar.

It wasn’t just in America that the Japanese dancer’s reputation soared. In London she performed for Edward, Prince of Wales. In Paris, Picasso painted her four times. She went on to tour with the then-unknown dancer Isadora Duncan through Germany and Austria to Russia, where Tsar Nicholas II held a banquet in her honour. And finally she reached Italy, where Puccini was working on his Madame Butterfly, based on a short story by the American writer John Luther Long and the popular play by David Belasco. So spellbound was Puccini by her performances in Milan that he radically altered his new opera, modelling his Cho-Cho-San on her. She became not just the role model for Madame Butterfly, but an icon herself.

Everywhere she went, she was celebrated. When she eventually arrived back in Japan in 1902, at the port of Kobe, there were crowds waiting to see her as she came down the gangplank. Photographs show her wearing a huge white hat and fashionable flouncy Paris gown, riding in her carriage through streets lined with people. She was Japan’s first woman superstar.

With the money they’d made traveling, she and Otojiro decided to make their base in Osaka where they built a brand new theater: the most advanced in Japan. In the West they had performed kabuki plays adjusted to Western taste. Here they would introduce Japanese audiences to Othello, Hamlet, Salome and La Dame aux Camélias.

Pictures of the grand opening of the Imperial Theater in February 1910 show an Edwardian-style music hall embellished with Japanese flourishes, and a kabuki-style walkway running through the audience. The area is now crisscrossed with boulevards lined with office blocks, and although it has long since disappeared, I wanted at least to get a feeling of the world in which they worked: the entertainment district where people flock to see bunraku theatre, with its realistic puppets enacting heart-rending tragedies, and traditional kabuki theatre.

The entertainment district today is nothing like the one in which Sadayakko would have worked. The heart of it, Dotonbori Street, is a pedestrian mall jammed with restaurants and bars, with a giant mechanical crab waving its claws above the city’s most famous crab restaurant, and lights so bright they hurt the eyes. There are restaurants selling every manner of food you can imagine; noodle stalls with three-dimensional golden dragons on the billboards overhead; restaurants serving blowfish that can poison you if not properly prepared; bars and cafés open 24 hours a day. Dotonbori canal runs alongside and on the bridge above the canal is a building walled with giant rectangles of pure light. It’s brash, noisy and exciting.

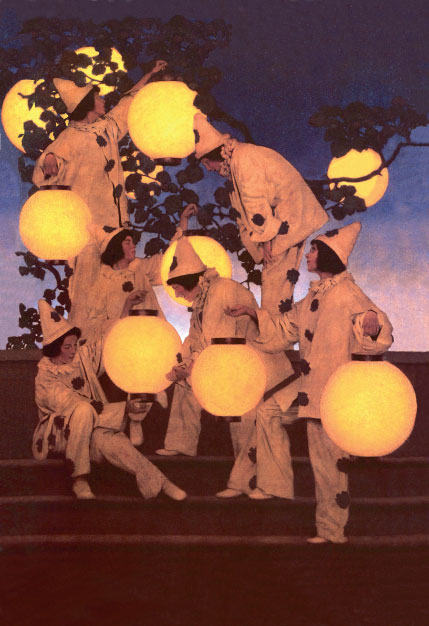

In Sadayakko’s day, things were simpler and quieter. Pleasure boats bobbed on the river, and low-rise buildings housed teahouses and restaurants hung with flags and lanterns, with people selling fireflies in cages outside. Just around the corner was the Shinmachi pleasure quarter and the geisha district, where Sadayakko would have felt completely at home.

Although in Osaka she and Otojiro lived extremely happily, building up a reputation for their theater, and their own performances, it was short-lived. In 1911, Otojiro fell ill and died shortly afterwards right on the stage, leaving Sadayakko a widow at the age of just 40. But Sadayakko was nothing if not a survivor. When she was a young geisha, a young man called Momosuke Fukuzawa had been the love of her life, and they had never forgotten each other. When he resurfaced, by now a business mogul, they rekindled their affections, and, leaving his wife behind in Tokyo, he set about building a mansion for Sadayakko in Nagoya, central Japan.

Thirsty for the next chapter in the actress’s life, I take the bullet train from Osaka, past the beautiful city of Kyoto, past paddy fields, plains and distant mountains. On arrival in the sprawling metropolis of Nagoya, bristling with buildings, I ask whether anyone knows of the house in which Sadayakko and her lover lived. The locals, I learn, called the house Futaba Palace, after the area in which it is situated, a suburb in the shadow of Nagoya Castle, with its impressive double keep and roof ends topped with giant bronze carp.

I take the subway to Futaba, a quiet residential district, where the house has been reconstructed. I round a couple of corners and there it is, with its precipitous red roofs, bigger and more ornate than I had imagined: like a grand country manor, with wood-panelled walls and heavy velvet drapes tied back with cords, and Art-Deco stained-glass windows depicting flowers and landscapes and languid ladies. There’s a tea ceremony room with sliding paper screens and an alcove with carefully arranged flowers. And there, in a case, are the courtesan’s embroidered kimonos and the 12-inch-high clogs which she wore when she thrilled the West with her dancing, as well as the gorgeous tea gowns, high-heeled shoes and feathered hats she brought back with her from Paris and New York. Beyond the great curved staircase down which Sada would sweep, in the couple’s private quarters, are photographs of Momosuke, handsome in his indigo kimono, with Sada in a simple checked kimono, her hair in an elegant chignon, kneeling at his feet.

Although this was clearly a house in which they spent a great deal of time, it wasn’t their only home, or their most impressive one. Momosuke’s business at that time was constructing hydroelectric dams along the river Kiso, nearby, and not wanting to be away from her, he built them a country villa halfway down the river.

As I discovered when I arrived in Japan 20 years ago, one of the great joys of traveling here is the train network: bullet trains supplemented by local services that go right into the heart of the countryside. The local train I take trundles off into the hills along the edge of the Kiso river, through spectacular mountain scenery. Forests plunge to the water’s edge, smoke-like clouds billow in the hollows and the mountain cherries are just coming into bloom. I get off at a village called Magome, stopping for the night to complete the journey, as the actress would have done herself, on foot.

Magome is little more than a stretch of inns and restaurants, a place where the present has yet to intrude, with no cars or electric cables visible. A huge waterwheel turns, creaking and splashing. I catch a whiff of wood smoke. The steep cobbled road is lined with wooden houses whose tiled roofs are weighted down with stones to keep them in place during the winter snows. There are balconies and sliding wooden doors, and strings of orange persimmons hanging out to dry. I look back from the top of the slope and see mountains looming blue in the distance.

Here, I spend the night in an old inn with an earth-floored entrance and watch the sun go down over the mountains from a bench. Lanterns glow, and I hear shouts and laughter from the inns along the street. I dine on grilled river fish, rice and lotus root, then climb the steep stairs to my room where my bedding is laid out on tatami mats.

Next morning, I set off early and walk to the top of the village from where the path plunges into thick bamboo glades and groves of cryptomeria trees. In Sadayakko’s time this was a major highway, known as the Inner Mountain Road, along which people used to walk or travel by palanquin on the long journey between Kyoto and Tokyo. Now it’s a woodland track, but still neatly paved with stones along its length, and shaded by a thick canopy of trees. In places, like the path up the Magome Pass, it’s so steep that it has been cut into steps. At the top there’s a teahouse, a weather-beaten wooden building with slatted doors. I peer inside, but it seems this place hasn’t been used for years.

Walking downhill to the Kiso Valley below, I glimpse a cluster of roofs. It is Tsumago, a working village that, like Magome, is determined to remain in the past. Even the postman wears 19th-century uniform. In the old days the larger villages along the road had an inn for VIP guests, and the one in Tsumago is particularly grand. In 1860 an imperial princess rested here on her way to marry the second-to-last shogun, and a few years later Emperor Meiji stopped to take refreshment. I tiptoe across the vast tatami-matted rooms and admire the decor. Inside, beautiful carved fretwork frames the paper doors and outside are two tiny gardens: one with a carp pond, the other planted with moss and decorated with two perfectly-placed stone lanterns.

I check into a more modest inn. Sitting outside in the evening, it is pitch black: there’s no moon and no street lighting. It seems to accentuate the rushing sounds of the river, the rustling of wild animals and the smell of fresh country air.

The next day I set out with a local historian called Takashi Toyama, who has lived here his whole life, in search of Sada’s country villa. The house which he takes me to couldn’t be prettier. Situated on a hill on the other side of the river, which we get to via a miniature Brooklyn Bridge, the three-storey 1919 house is handsomely constructed from rounded stones taken straight from the Kiso below. There is a balcony and a conservatory with tables and wicker chairs where the couple would sit and admire the river, a dining room for entertaining, and a lounge with chandeliers and huge windows that they would throw open. It’s a lovely, breezy country retreat.

Toyama then takes me to see Momosuke’s dams. He built seven in all, beautiful stone constructions decorated with Art-Deco designs, which continue to supply Kyoto and Osaka with electricity to this day. It’s amazing to realize that some of that extraordinary neon back in the city is powered by rainfall in these beautiful mountains. En route, to my delight, I meet a beaming, wizened old man who remembers seeing Sada on her red motorbike, bumping along the rough country roads in Western clothes, back in the early 1920s, when he was a very small boy. She used to smile at him and give him chocolate: a rare treat in this tiny out-of-the-way village, where no one knew who she was or cared what she did.

After the dams had been completed the couple spent most of their time in their palatial home in Nagoya, but they still found excuses to come back to their rural home here. It was a place to which Sada could return to the traditional old Japan of Madame Butterfly, with its white-faced geisha and the plangent melancholy notes of the shamisen, its tea ceremonies and flowers arranged with Japanese precision.

Strolling around the rooms, with their cabinets full of memories, Sadayakko’s fans and parasols and old photographs, I can almost see her here with her beloved Momosuke, dancing for him in her embroidered kimono, with her hair in a bouffant coil, or on her knees whisking up green tea in a priceless stoneware tea bowl. For a moment, if I close my eyes, I almost forget that I’m in a country whose landscape is traversed by bullet trains and whose skylines are dominated by soaring steel and glass buildings. In my quest for Madame Butterfly, I have discovered something equally beautiful: the real old Japan.

Photographs: Magnum Photos

Your address: The St. Regis Osaka