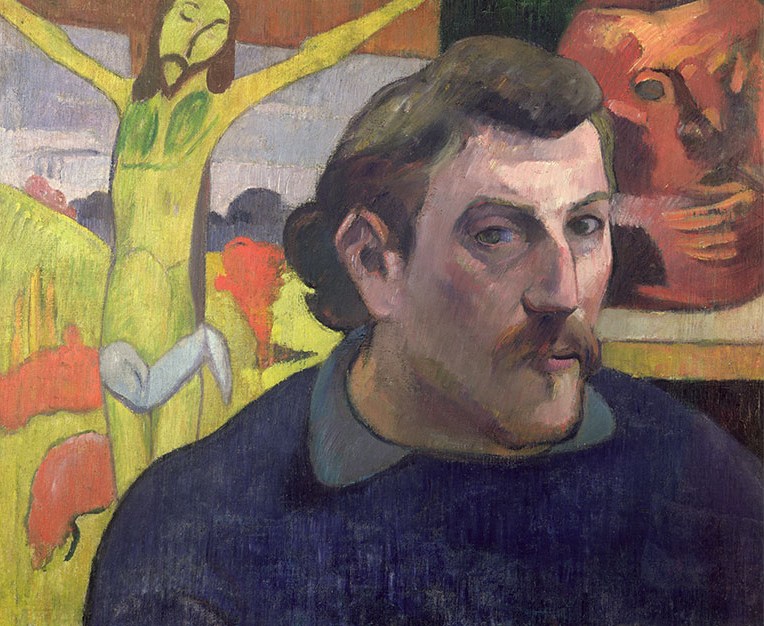

As the critics like to tell us, though, Gauguin’s paintings were a fantasy. He yearned to escape bourgeois routine, to find the primitive and essential. Unfortunately for him, the London Missionary Society got here first. In the Musée de Tahiti et des Îles, I contemplate black-and-white photos of local families taken from the 1860s onward, in which all the women wear decidedly unrevealing full-length dresses known as “Mother Hubbards”. My driver-guide is entertainingly blunt on this. “First the English came, telling us to cover up,” he says. “Then the French came, telling us to undress. We prefer the latter.”

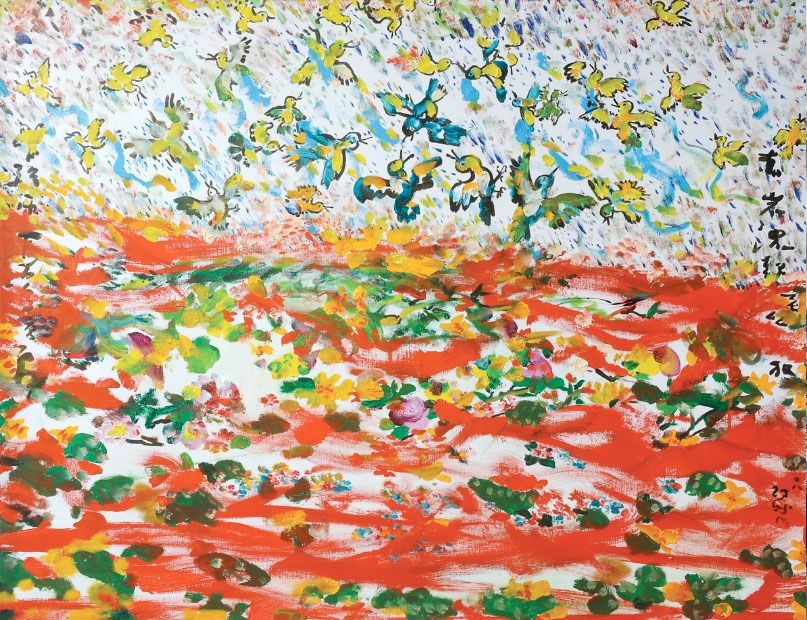

Tahiti is actually two islands linked by an isthmus, and as I drive around its figure-of-eight, admiring the mighty forest-cloaked mountains and black-sand beaches, it is not hard to find scenes straight out of Gauguin. A horse grazes in a field of luminous grass, mangoes ripen on a table, vahines (Polynesian women) with long dark hair and a bright flower behind the ear relax on the beach. “Everything in the landscape blinded me, dazzled me,” the painter wrote. Once here, it was natural to paint a red close to a blue. “There is a continuing supposition,” argues his biographer David Sweetman, “that Gauguin invented his own Tahiti, particularly in respect of his colors, but one can only hold to such a view if one has never visited.”

Most visitors use Tahiti only as a stepping stone to the other islands, but it is worth a tour. Highlights include the Plateau de Taravao viewpoint, the dramatic surfing spot of Teahupo’o, and Mataiea, where the painter retreated to live in a bamboo hut. It’s sad but understandable that there are few original works by Gauguin to be seen on the island and that the Gauguin Museum, which has them, is currently closed for lengthy renovations. If you want to behold the art that resulted from this great creative adventure you’ll need to visit major galleries in cities such as New York, Boston, Paris and St. Petersburg.

But the real subjects are everywhere. Looking across from Tahiti to the graph-like peaks of neighboring Mo’orea for the first time, I’m as stunned as Gauguin was. “The mountains stood out in strong black upon the blazing sky,” he noted, “all those crests like ancient battlemented castles.” At times the sunsets here are so magnificent they fill the sky like a prelude to the Second Coming. Why isn’t everyone on their knees praying, I wonder? Because this is a tropical outpost of France, and everyone is far too busy buying baguettes, puffing on cigarettes and driving erratically.

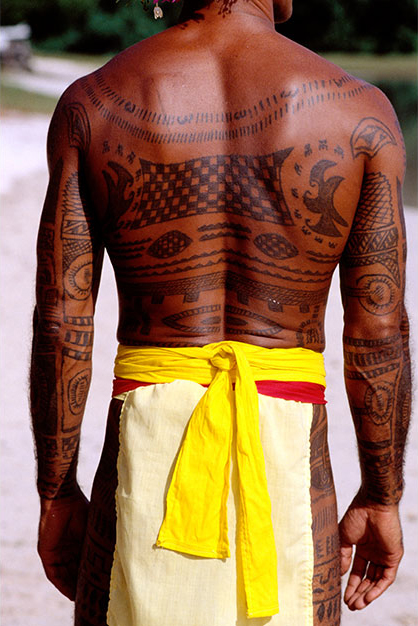

Gauguin never made it to Mo’orea, but I can’t resist whizzing over by high-speed ferry, which takes 35 minutes and provides a chance to mingle with the sturdy, tattoo-covered, ever-smiling Tahitians who so enchanted the French painter. Here I join a Jeep tour that takes a roller-coaster drive inland to savor panoramic views and visit pineapple estates and marae (historic sacred sites). While French Polynesia is traditionally seen as a place for scorching romance and sipping coconut cocktails on the decks of over-water bungalows, it clearly offers much more: 118 islands, in fact, sprinkled over an area the size of Europe, but with just 275,000 inhabitants. Rather cheekily, Air Tahiti, the domestic airline, prints its route map superimposed on this continent, with Papeete standing in for Paris and its services shooting off to the equivalent of Bilbao, Stockholm and Istanbul. Point made – French Polynesia is one huge, adventure-packed chunk of paradise that cries out to be explored. Diving the shark-filled Tiputa Pass in Rangiroa, swimming with whales in Rurutu, visiting the pearl farms and vanilla plantations of Taha’a, admiring the coral churches of the remote Gambier archipelago – it is all most enticing.

One place on most wishlists is Bora Bora, a 50-minute flight west of Tahiti. “So beautiful they named it twice” quip the t-shirts, and its reputation as a scenic stunner is deserved. The island presents a sensational pairing of dramatic tooth-like peaks and bewitching blue-green lagoons, and owes its fame in part to the Second World War, when U.S. forces built an air base here following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Among their number was a young naval officer, James A. Michener, whose 1947 Pulitzer Prize-winning book Tales of the South Pacific, which inspired the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical South Pacific, shone a spotlight on this balmy paradise. Until the 1960s, when tourism started to develop, Bora Bora was one of the few places you could fly to in French Polynesia, and it has since developed a reputation as the destination for honeymoons and landmark celebrations.

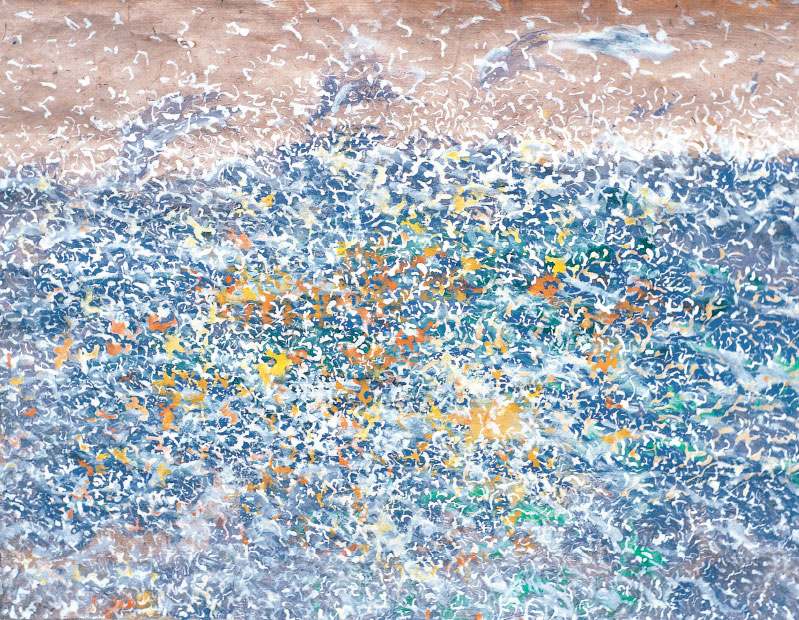

“Have you ever seen green clouds?” a boatman asks as I speed across its divine waters. He points up to the sky, and I see what he means. At times the lagoon here is so intensely emerald that the sunlight bouncing off its surface gives the puffy clouds above a mesmeric, jade-like sheen. Gauguin would have noticed such things, I’m sure, just as he would have appreciated the tremendous sunsets now enjoyed by guests at The St. Regis Bora Bora Resort, which rests on an eastern motu (islet), with a necklace of luxurious over-water villas, offers grandstand views.

For me, it isn’t the soaring silhouette of Mount Otemanu backed by an apricot glow that most impresses; it’s the sights after sunset. When the sun has slipped away but the darkness of night, heralded by the first silvery stars, has yet to take hold, the sky becomes a magical, fleeting shade of indigo. You might even want to paint it… On the other hand, by this time you will surely have sipped a cocktail or two, such as the intriguing watermelon-infused Bora Mary, the signature drink at The St. Regis. Then it will be time for dinner, perhaps on the beach, à deux, with flaming torches. A little poisson cru à la Tahitienne, some roasted spiny lobster with mango. Could life ever get more romantic?

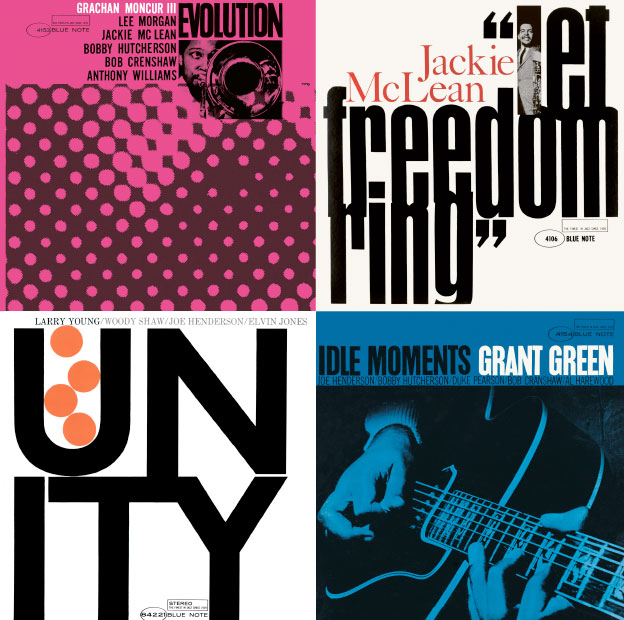

Gauguin returned to France in 1893, where 42 of his Tahitian paintings were exhibited that autumn in Paris, receiving little acclaim. These include the now-celebrated Vahine No Te Tiare (Woman with a Flower) and Manao Tupapau (Spirit of the Dead Watching), which are today in galleries in Copenhagen and Buffalo respectively. Two years later the artist was sailing south again, on a trip from which he never returned. His entire life had been spent rejecting things: wife, children, France, friends, agents, Van Gogh… The final destination this time was the Marquesas Islands, which lie almost 900 miles north-east of Tahiti. For the 19th-century adventurer, let alone a man now ill, penniless and despondent, it was the equivalent of a voyage to Mars.

It took Gauguin five days to sail here from Papeete, but I choose to follow in his wake aboard Aranui 3, a “freighter to paradise” that carries both passengers and cargo. It’s a comfortable but unconventional cruise – there are lectures and entertainment, but the crew are informally dressed and there is a clear sense that we are here to do important work supplying French Polynesia’s far-flung islands. We deliver everything from cars and cement to peanut butter, and then pick up copra and noni fruit for export. One of the deepest joys of this voyage is being lost amid the vast blue saucer of the South Pacific. At night, up on deck, relishing the warm breezes and a sky peppered with stars, I can’t help thinking of the Polynesian navigators who ventured across these waters in their huge canoes as early as 2000 BC.

While the crew get busy loading and unloading, passengers take excursions. One key stop is the 78 coral atolls known as the Tuamotus, where the horizon is adorned by a long trail of cartoon desert islands. Renowned for their diving, this is where another great French artist, the 60-year-old Henri Matisse, came in 1930. Like Gauguin, he was drawn to Polynesia’s extraordinary light and color. On Fakarava he went snorkeling, donning wooden goggles to admire the vivid fish, corals and “undersea light like a second sky” – sights that would inspire later works, such as the two Oceania cut-out wall-hangings, dancing with vibrant fish, corals, jellyfish, birds and leaves, that are now in the National Gallery of Australia.

Ten degrees south of the equator, the 15-strong Marquesas are the island group farthest from any continental land mass. Their atmosphere is markedly different from Tahiti, and it is easy to believe they were once peopled with club-carrying cannibals tattooed from head to toe. Rising to 4,000ft, their steep volcanic peaks are blanketed with thick forests that confine village life to narrow valleys and beaches fringed with a waving green sea of coconut palms. Serial escapists can’t keep away. In 1842, Herman Melville jumped ship on Nuka Hiva, his experiences inspiring his first best-selling novel, Typee. Jack London passed through in 1911, and in 1937 a young Thor Heyerdahl lived on Fatu Hiva for a year, trying to lead the simple life as the world moved towards war.

Gauguin only made it to one of the Marquesas, Hiva Oa, and today his simple grave lies in a hilltop cemetery overlooking the capital, Atuona. It is often adorned with flowers and mementos from the trickle of fans who make it here, and I am moved to pay my respects, too. As with many great artists, Gauguin’s personal life was far from exemplary, but no one could argue with the sensational work he created in his “Studio of the Tropics”. He painted his dreams, but after my 2,000-mile tour through the enchanting islands of French Polynesia, I have only one conclusion: the reality is even better.

Your address: The St. Regis Bora Bora Resort

Images by Getty Images, Burt Glinn/Magnum Photos, Ferdinando Scianna, Bridgeman Images