Anyone who remembers how the classic car boom of the late 1980s ended in a dramatic bust might be inclined to steer clear of sinking their life savings into a collection of old automobiles. But perhaps they should think again. A cursory look at the prices being achieved for the most sought-after models shows that the market is currently at an all-time high.

A prime example of its buoyancy was seen in February of this year when French house Artcurial set a new record price in Euros for any car sold at auction by hammering down a 1957 Ferrari 335S Spider Scaglietti for €32.1 million (about $35.7 million). Two years ago, the highest price ever achieved for a car in dollars was reached at Bonhams for a 1962 Ferrari GTO: $38.1 million. The message is clear: classic cars are now officially regarded as blue-chip investments, with their value increasing at a higher rate than the stock market, property and even gold. In the 2015 passion investment index by the private wealth managers Coutts, certain classic cars showed an increase of 40 per cent in 2014 and a 400 per cent increase since 2005.

Not that the appeal of old cars is purely financial. For most buyers, the real pull lies in the fact that they are rolling works of art that not only look great and evoke a golden era but offer the potential for a huge amount of fun, too. In recent years, the number of events being staged for veteran, vintage and classic automobiles has grown exponentially. Today, instead of just polishing your pride and joy and taking it for an occasional weekend jaunt, you can actually use it for anything from an organized tour with a group of like-minded enthusiasts to a road rally, hill climb or all-out circuit race. In May, for example, the biennial Monaco Historic Grand Prix saw hundreds of vintage and classic cars racing around the legendary circuit in seven different classes catering for everything from 1930s Bugattis to the wildest Formula One cars of the 1970s. So, if you fancy owning a classic, which should you buy? The choice is, of course, myriad, but here are five that are on the wish lists of most lovers of historical cars.

Jaguar E-Type

Created by former aircraft designer Malcolm Sayer, Jaguar’s E-Type was the fastest production car on the market when it was unveiled in March 1961. With a top speed of 150mph, a 3.8-liter, 265-horsepower engine and jaw-dropping looks, it was declared by Enzo Ferrari to be “the most beautiful car in the world”. More than 72,000 were built during a 14-year production run. The most popular, however, are the “Series 1” models, with the best open-top “roadsters” currently commanding around $250,000, and fixed-head coupés only half as much. Jaguar recently built a series of six “continuation” cars to finally finish the Lightweight E-Type project which, 51 years ago, resulted in the creation of a series of highly-focused racing versions of the car. Only 12 of the intended 18 cars were ever made, leaving the remaining half-dozen allocated chassis numbers on file. These were used by Jaguar’s Special Operations division to build the “missing” Lightweights, which sold for more than $1.5 million each.

Ferrari 250 GTO

Said by many to be the most beautiful car ever created, a mere 39 examples of the legendary 250 GT “Omologato” were produced between 1962 and 1963, originally to contest the FIA GT World Championship series in the three-liter class – the “250” in the title referring to the 250cc capacity of each of the engine’s 12 cylinders. Although designed as a pure racing machine, the GTO is renowned for its ease of use as a road car. The most paid at auction to date is $38.1 million, although one example is rumored to have changed hands in a private deal for closer to $50 million.

Porsche 911 Carrera RS

The Carrera 2.7 RS of 1973 was intended purely for racing, but Porsche had to build 500 road-going examples to qualify the car for inclusion in the Group 4 GT category. It proved so popular as a high-performance street machine, however, that production only stopped after 1,508 had rolled off the line. Much of the appeal of the RS lies in the fact that it combines 150mph performance with reliability and surprising economy. The best examples now fetch between $1 million and $1.5 million, but beware: early 911s are notoriously dangerous in the hands of the uninitiated. When cornering, the golden rule is “slow in, fast out”, because if you lift off the throttle on the apex of a bend, there’s a good chance it will spin off the road.

Bentley "Blower"

“The world’s fastest lorries” is how Ettore Bugatti rather rudely described the pre-war Bentleys that dominated the Le Mans 24-Hour races during the late 1920s and early 1930s. The “blown” 4.5-liter Bentley was unveiled at the London motor show in 1929 having been privately developed by “Bentley Boy” Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin as a higher-performance version of the standard four-liter. Just 50 production cars were built, all of which could top 100mph, making them among the world’s first supercars. Examples rarely appear for sale, but those that do command sums in the region of $1.5 million. Four years ago, however, the 1932 single-seater, record-breaking Blower that originally belonged to Birkin fetched a record $7 million at Bonhams.

Lamborghini Miura

Made famous in the opening scenes of The Italian Job, in which a bright-red example can be seen driving along an alpine road to the strains of crooner Matt Monro’s On Days Like These before being pushed off a cliff by a Mafia bulldozer, the Miura was the first ever mid-engined, road-going supercar when it was launched in 1966. According to legend, it was designed by Lamborghini engineers in their spare time, as company boss Ferruccio Lamborghini was more interested in grand tourers. Featuring a 12-cylinder, four-liter engine, Miuras are known for their brutal power, weighty gearshift and over-light front end. But on a challenging back road with a good driver behind the wheel, thrills are guaranteed. Add to that a range of wild color options and past owners ranging from Frank Sinatra to the Shah of Iran, and you can see why values have risen from $800,000 five years ago to more than $2 million today.

Images: Getty Images, Alamy

Two years ago, a friend I hadn’t seen in years phoned me from Washington, D.C. He was in the city on business and knew I lived in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, but he said he didn’t have time to visit “the South”. I told him something that surprised him. “You’re in the South, Jonny. Look out of your hotel window. That’s Virginia on the other side of the Potomac River. I live 50 miles west of there. Tell me when you’re free, and I’ll take you on a drive. It’s another country out here – great characters.”

I understood my friend’s surprise that cool, cosmopolitan D.C. was a Southern city, largely because I had to amend my own hoary clichés about the South when I moved here from New York five years ago to a historic 1733 Quaker village named Waterford, in the Piedmont region of rural northern Virginia. We could see the Blue Ridge, part of the Appalachian Trail, from our front porch.

We’d moved because my wife, a dyed-in-the-wool Yankee, wanted our kids to feel the grass beneath their feet, but still have proximity to D.C. I wanted all the Southern stereotypes: mint juleps, crumbling antebellum mansions, redneck moonshiners tending stills on starlit nights. What we got was something so utterly different it still surprises me today.

The land around us turned out to be far more Hamptons than hillbilly. Luminous green meadows dotted with sheep and horses stretched to the horizon; historic country homes with wrought-iron gates and oak-shaded driveways stood sentinel on hilltops, like mansions out of Edith Wharton novels. On any given weekend, we would drive winding, stone-fenced country lanes to our local tavern and run into scarlet-jacketed fox hunters riding to hounds. Loudoun, it turned out, was the richest county in America.

But the wider region was rich, too – in history. The land between the Blue Ridge and Route 15, a narrow north-south blacktop that runs 180 miles from Pennsylvania, past Waterford, on down to Charlottesville, Virginia, is one of the most historic corners of the U.S. It’s The Place Where America Happened. No fewer than nine presidents have lived on it or nearby; some of the greatest battles of the Civil War, including Bull Run (first and second) and Antietam, took place here, and world historic documents, from the Declaration of Independence to the Constitution, were either drafted or inspired by events on its route.

My friend had two days to spare, and I took him on the drive I take all visiting friends: a 350-mile loop from the Capitol, west on Route 50, through the chic horse country towns of Middleburg and Upperville (where Jackie Kennedy rode to hounds), and down Skyline Drive on the crest of the Blue Ridge into rural Rappahannock County. We would stop at Montpelier, family home of James Madison, father of the Constitution, then loop back up Route 15, Highway of Presidents, arguably the most eventful road in U.S. history.

I picked him up at the St. Regis, where he was staying, and we did a brief Capitol tour, cruising past the Lincoln Memorial on The Mall, and the Jefferson Monument along the Potomac. No fewer than eight U.S. presidents were born in Virginia, the Old Dominion, including four of the first five. George Washington’s grand estate, Mount Vernon, stands on a high bluff overlooking the Potomac near Alexandria to the south of us; it’s not on our route but it’s an essential stop for any D.C. visitor.

For the first 40 minutes, Route 50 is bumper-to-bumper through the suburban sprawl, but nearing Aldie, a strange thing happens. As if you’ve crossed a border, the development clears, and you’re suddenly in glorious countryside: luminous green fields; forests of maple, oak and birch; the Blue Ridge Mountains shimmering in the distance.

Route 50 meanders 3,000 miles from Maryland, through America’s heartland to California, but the 30 miles where it passes through Aldie, Middleburg, Upperville and Paris in the Piedmont are arguably the most gorgeous 30 miles in Virginia. The towns date back to the 1700s, when the road became a busy route for traders from colonial Georgetown and Alexandria accessing the farms of the Shenandoah Valley across the Blue Ridge. Stables, inns, taverns and mills opened to cater to passing carriages and horsemen, and as the settlements grew, grand estates sprang up on their outskirts. Today, Middleburg is a sort of Hamptons for the D.C. set, but with horses instead of beaches.

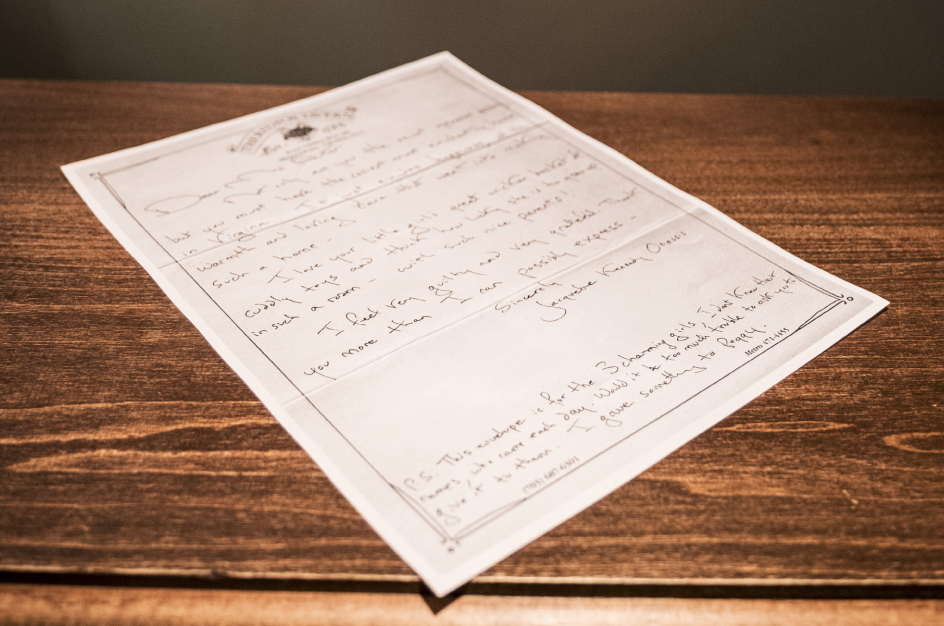

I park outside Country Classics, a raffish boutique selling tweed coats and cravats, and watch as blondes in jodhpurs and leather riding boots step out of mud-splattered Range Rovers. Middleburg is the heart of the Mid-Atlantic show-jumping, steeplechase and fox-hunting scene. Even the coffee shop is called the Giddy Up. We pop into the Red Fox Inn for coffee, the oldest building in town, a low-slung fieldstone “ordinary” from 1729 that reminds me of the Dickensian taverns of London. Above the front desk are gracious thank-you letters signed by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, from visits the former First Lady made here in the early 1980s.

It was Jackie Kennedy who put Middleburg firmly on the map, 20 years prior to penning those letters. When J.F.K. was president, she wanted a weekend retreat from the White House for her and the children. The Kennedys rented Glen Ora, a grand estate south of town, one of those sprawling mansions with oak-shaded driveways. Jackie joined the Orange County Hunt, her kids attended the local pony club, and the paparazzi followed. Middleburg was never the same again.

We pop across the street to The Home Farm Store, a former bank converted into a gourmet food store by Cisco Systems co-founder turned organic farmer, Sandy Lerner. Everything here is from Lerner’s farm, Ayrshire. After a six-dollar Scotch egg, we motor west. It’s early afternoon and the Blue Ridge shimmers above fields of boxwoods and beech. Then, like a mirage, a red British phone box appears as we enter Upperville. Welcome to the Hunter’s Head, my favorite country pub.

The tavern is a warren of cozy, low-ceilinged rooms, their walls covered with cartoons of foxes in riding hats. Built as a farmhouse in 1750, it looks like it’s been serving ale to ruddy-faced regulars since George Washington’s time. We tuck into bangers and mash with fresh bread, then walk off lunch in the village. It’s tiny, with the handsome sandstone Trinity Church, a few stone houses hugging the road, and a gun shop selling vintage muskets and Remingtons. As John Updike noted in a 1961 poem for The New Yorker, Upperville is even fancier than Middleburg:

In Upperville, the upper crust

Say “Bottom’s Up!” from dawn to dusk

And “Ups-a-daisy, dear!” at will

I want to live in Upperville.

“Mr. Rogers, cocktails in the parlor at 6.45pm. Don’t be late!” It’s time to meet some local characters, including Nat Morison, 76, seventh-generation Virginia Brahmin, owner of Welbourne, a 1770s country estate on a rutted dirt road, 15 minutes’ drive away (near the famous Foxcroft School for girls).

Welbourne, a custard-yellow colonnaded mansion on Nat’s 500-acre family horse farm, is a Piedmont mansion that doubles as a guesthouse. It was turned into an “invitation-only” inn back in 1930 by Nat’s grandmother. Thomas Wolfe and F. Scott Fitzgerald were invitees, and both wrote stories about it. I stay in Wolfe’s room (creaking four-poster) just past the library, where an imposing portrait of Nat’s bearded great-great grandfather, Confederate Colonel Richard H. Dulany, stares at me from the wall. Dulany rode with the great Gray Ghost, guerilla fighter John S. Mosby, in the war, and road signs throughout the Piedmont still venerate “Mosby’s Confederacy”, as the region became known.

You visit Welbourne for warmth and character, not frills. Sherry, Nat’s garrulous Connecticut-born wife, gives us “the tour”: three floors of dust-covered armoires, antique travel chests, shelves cluttered with faded Country Life magazines and leather tomes on war and horses. Picture Downton Abbey, if Carson, Mrs. Hughes and the rest of the staff had gone to the village fair 30 years ago and never returned. The music room (Nat collects – and plays nothing but – pre-1930s New Orleans jazz 78s) has a still-working Aeolian Vocalion gramophone and an out-of-tune 1907 Steinway. “It’s the eternal question,” Sherry sighs. “Fix the pipes or the piano?”

To me, this sounds like an unmistakably English sensibility, but when I mention this over cocktails (Virginia Gentleman bourbon on the rocks), Nat bellows at me like I’m crazy. “England? How would I know? I’ve never been out of America – except to New Orleans.”

In the morning, we motor south, leaving Route 50 for Fauquier County on a narrow, stone-fenced lane towards The Plains. A promising sun is burning off yesterday’s cold, and the land changes subtly here, becoming flatter and drier, yellow grass in open fields making it resemble Montana. The Plains are aptly named. The actor Robert Duvall has a horse farm here and is a regular at the local Virginia Gold Cup steeplechase in May, the Piedmont social event of the year. My Waterford neighbor,Tom, a political consultant, tells me he does more business in one afternoon at the Gold Cup than he does in a month at the Capitol.

It’s time to hit the Blue Ridge, and from The Plains we drive due west, detouring through the orchards, hollows and deer-specked valleys of Naked Mountain, part of Sky Meadows State Park, before accessing Skyline Drive at the resolutely blue-collar Front Royal. Built in the 1930s as a public works project, Skyline Drive is a spectacular 105-mile traverse running north-south through Shenandoah National Park on the crest of the Blue Ridge. There are 75 cliff-edge viewing points on its course and low hanging oaks and willows form a natural tunnel part of the way. To me, Skyline Drive is more than a road; it’s a barrier and symbol. Below, to the west, the Shenandoah Valley, its great river a muddy snake on the plains, is the start of the American heartland, while down to the east, the Piedmont, as green and delicate as a country garden, clings to the ways and manners of the Old World.

Skyline Drive ends in the town of Charlottesville, home of another Virginia President, Thomas Jefferson, author of the original American document, the Declaration of Independence. His majestic plantation, Monticello, which he built in French Revival-style, stands atop a hill overlooking a sea of green forest. Somehow, 230 years of development in the nation he helped found have not encroached on his view.

We don’t have time for Charlottesville, though, and instead keep it local, exiting Skyline Drive on Route 211 at Thornton Gap, descending into Sperryville, a river-splashed Piedmont farming town somnolent in the shadows of the Blue Ridge. Seventy years ago this was a bustling outpost, last stop before the mountain for traffic heading south-west to New Orleans and beyond. Then, in the 1950s, the highway was built at Front Royal, and Sperryville fell into slumber. In retrospect, it saved the town. Today, it’s a bucolic retreat with a creative subculture of organic farmers, artists, chefs and artisans. I make my way to the River Arts District, former apple-packing sheds on the Thornton River, converted into studios, galleries, and a tapas restaurant.

The highlight is the Copper Fox Distillery, where fortysomething Rick Wasmund makes award-winning ryes and whiskeys using a unique technique: he accelerates the aging of his spirits by adding a sachet of small “chips” of charred wood (oak, apple, and cherry) to the aging barrel, increasing the wood surface area. The result is astonishing: rich, smoky spirits with a delicate, fruity finish. I ask him how he came by the method, and he tells me he was caretaker at an old mansion in Middleburg that had eight fireplaces. “I had to light them every night, and I got to experimenting with smoke and wood, which got me to thinking about whiskey.” A brief stint at a distillery in Scotland and, lo, an idea was born.

We consider the power of ideas an hour later. We have taken the scenic 231 South for an hour and found our way to another presidential home: Montpelier, home of James Madison, the fourth president. A handsome two-floor neoclassical mansion on a 2,500-acre estate, Montpelier was built by Madison’s father in 1764, and remained in the family until 1840. In 1901, it was bought by the duPont industrialists, who added a garish mural to its façade and a steeplechase track – as you do. But in 2008, after a painstaking $24-million restoration, it was returned to the way it originally looked back in Madison’s day.

From the second-floor library, I look out on the same incomparable Blue Ridge view Madison had surveyed in 1786 as he considered all those weighty questions. A towering intellectual, he read more than 400 books in seven languages while he was drafting the documents that would form the basis for the U.S. Constitution, including, as our guide explained, texts in original Latin, Hebrew and Greek. “They don’t make ’em like that anymore,” someone next to me mumbles.

It’s late afternoon by the time we double back on to Route 15, now part of The Journey Through Hallowed Ground national heritage area that links Jefferson’s Monticello to the Gettysburg battlefield in Pennsylvania, 180 miles to the north. Several other battles took place at points along its route including Manassas, site of the First Battle of Bull Run, the brutal first big clash of the Civil War. Waterford, my own town, lies just off it. I take Jonny to see it before driving him back to the St. Regis in D.C. We sit on the porch sipping a bourbon as the sun sets over Blue Ridge. For some reason I think of New York City and the big move south. I have no regrets. I’m in Virginia, where America began.

Your address: The St. Regis Washington, D.C.

A South Indian

restaurant in Mumbai

by Naeem Khan

Trishna, Sai Baba Marg, Kala Ghoda, Fort, Mumbai

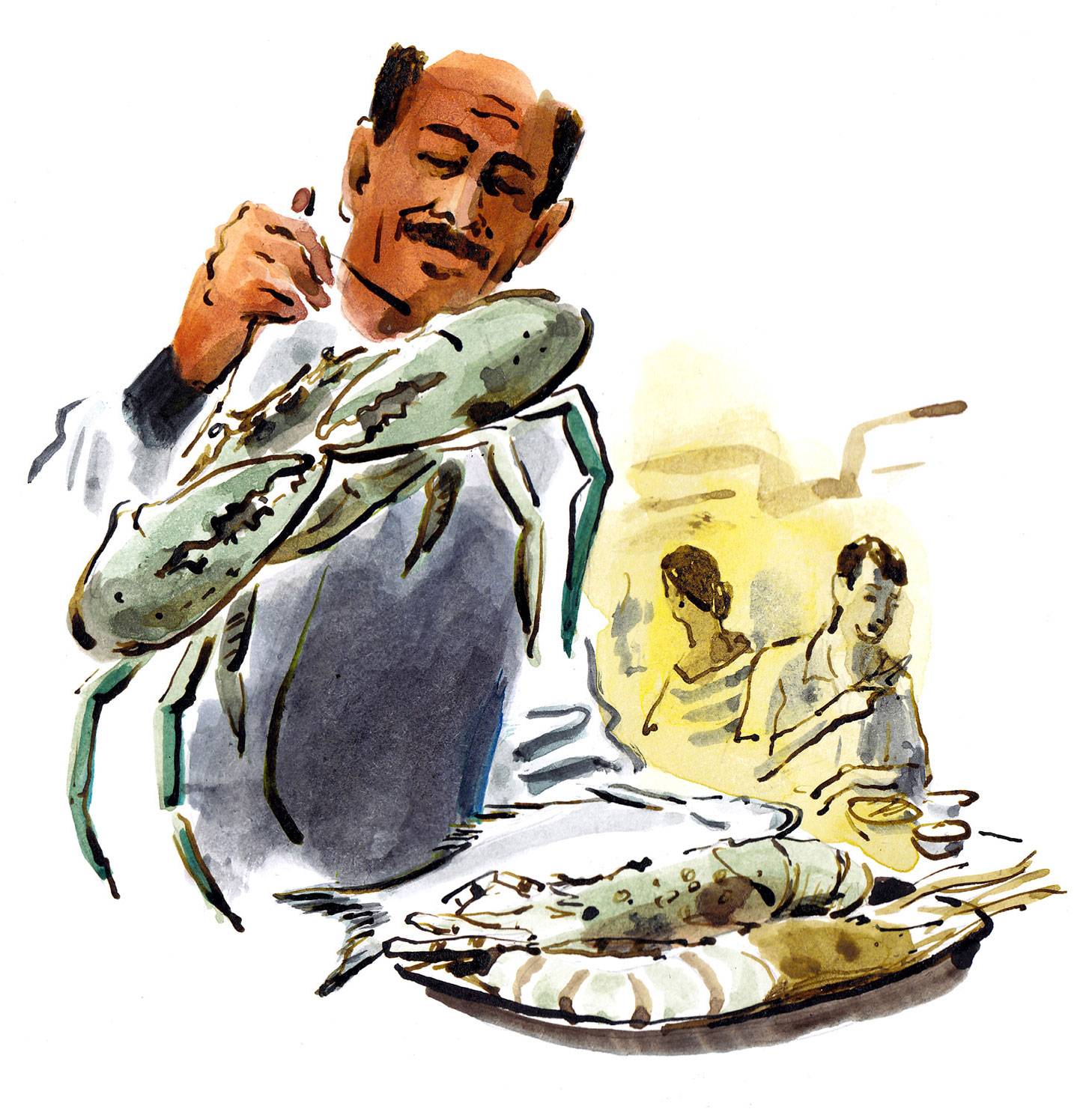

I first ate at Trishna ten years ago, and now whenever I’m back in Mumbai I just have to go there. The restaurant is hidden away in a back street in the Kala Ghoda area, which has a lot of art galleries and cafés. It’s been there for about 50 years and is owned by a family from Mangalore, which is on the coast in South India. As Mumbai restaurants go, it’s not particularly cool or fashionable, but it serves the best food in the world. The first time I went to Trishna I was a bit surprised – the furniture is basic, it’s quite dark, with pictures of Mangalore and a large fish tank – but I’d heard so much about it from my brothers I thought, “OK, I’m willing to experiment.” Since then it has become a bit of a hotspot, with a more international clientele, though the décor hasn’t changed. The menu mainly consists of Konkani or Mangalorean cuisine, so there’s a lot of fish and seafood. The best thing is the giant crabs. The way they prepare them with chili and garlic is just incredible. For me, Trishna is the taste of India. It’s not northern Indian cooking, which is predominantly Mughal, it’s South Indian, which means things like light coconut curries, steamed lentils, seafood and grilled fish, so it’s much healthier. It’s spicy though, which I love. For Indian food to be really special the ingredients have to be totally fresh. At Trishna you can tell that the coconuts have just been picked and the spices are all freshly ground. The crabs couldn’t be fresher: they actually bring a huge live crab to your table before they cook it. These days I go to Trishna about twice a year, usually for a family gathering. My brothers and sisters and I have been going there for 10 years, so it has a lot of happy memories. Going there has become a kind of joyful family ritual, with delicious food.

Naeem Khan is an Indian-American fashion designer based in New York

Your address: The St. Regis Mumbai

A vintage perfume

shop in Bangkok

by Simon Westcott

Karmakamet, Chatuchak Weekend Market, facebook

This tiny little perfume shop is the sort of place you really have to look out for. Actually, you’ll probably smell it before you see it. Inside, it feels like an old-fashioned Thai pharmacy, full of dark wood shelving with scratched mirrored walls and medicine cabinets stocked with the most beautiful candles, fragrances and perfumes. The brand has been around since the 1970s, and the shop since 2001, selling the most intoxicating melange of essential oils, room fragrances, perfumes and all things scent-related. Although they use ingredients from all over the world, there’s a distinctly Asian influence in their scents, which include East Indian Sandalwood, Silver Needle White Tea and Siamese Lemongrass Peppermint. Each product comes in such beautiful vintage, hand-made packaging that you almost don’t want to open it. I’ve got so addicted to their scents that whenever I’m in Bangkok, I stock up. Products I buy most are the room diffusers, in scents like the earthy, masculine Egyptian Fig and zingy, fresh Pomegranate; travel candles, which I take wherever I go; and stashes of things to give as gifts. Last time I bought a Siamese Lemongrass Peppermint candle, and whenever I light it, I’m transported back to leisurely evenings in Thailand, sitting in the warm, heady heat listening to the cry of a nearby gecko. Lots of brands have tried to emulate it, but this place is the real deal.

Simon Westcott is head of Luxe City Guides, which offers sophisticated, opinionated pocket-sized guides to 36 cities around the globe

Your address: The St. Regis Bangkok

An Istanbul emporium

of objects for bathing

by Rifat Özbek

Abdulla, beside Fez Café, Grand Bazaar, abdulla.com

If I had to recommend just one shop in Istanbul it would be Abdulla, on Halicilar Street in the Grand Bazaar. It’s a totally unique shopping experience that offers the best of traditional and contemporary Turkey. The bulk of what Abdulla sells was made especially for the hammam, or Turkish steam bath. He has the very finest quality hand-loomed peshtemals, or Turkish towels, which are 100 per cent natural cotton, luxuriously thick and tasseled. He has such a beautiful range, all neatly folded in perfect little piles. As well as stocking specialist objects for the hammam, such as takunyas (wooden hammam slippers), keten zincir (scrubbing mitts), ponza (scrubbing brushes) and tas (small metal bowls), Abdulla also sells robes, scarves, hand thrown ceramics and a few fun pieces and divine vintage treasures that may include a rare piece of tribal jewelry or clothing. His soaps have a great following because they are 100 per cent natural, made with olive oil and scented with herbs and flowers: juniper, sandalwood, nettle, almond, citronella. He really has done all the work for you when it comes to sourcing and manufacturing using the best local craftsmanship. Once you’ve browsed his wonderful wares you can pop next door to his Fes Café, with its wonderful old brick arched ceilings, for delicious traditional treats such as baklava and sweet apple pie, accompanied, perhaps, by a cup of thick Turkish coffee or fresh mint tea, served on a beautiful old metal tray, with a glass of water and a little toothpick with a square of delicious lokum, or Turkish delight. A lovely way to end a shopping trip.

Rıfat Özbek is a Turkish fashion designer who transforms vintage fabrics into cushions sold at Yastik in Istanbul, Le Bon Marché in Paris and Dwell in New York

Your address: The St. Regis Istanbul

A museum of

Islamic antiquities

in Cairo by Dr. Zahi Hawass

Gayer-Anderson Museum, Ahmed Ibn Tolon, sca-egypt.org

The Gayer-Anderson Museum is situated right next to the oldest mosque in Cairo, Ibn Tulun. The building it’s housed in has had many owners over the years, one of whom was a woman from Crete, which is how it became known as Beit al-Kritliyya [“house of the Cretan woman”]. It actually consists of two houses. Between them there’s a passage leading to the eastern door of the mosque. When I was young, I used to travel from my village to stay with my aunt. I would visit the pyramids and then play soccer with friends in the streets around this house. The first time I saw it, something about it touched my heart. Its architecture is truly unique. The museum itself takes its name from Major R.G. Gayer-Anderson, an English army officer who in 1935 wrote a letter to the Committee of Arab Antiquities asking to live in the house. He told them he would furnish it in Islamic style, and fill it with precious antiquities. He also promised that, when he died, he would leave everything to them. The committee approved and Anderson began collecting Islamic furniture and artifacts from Egypt, Syria, Asia, Persia, China and Europe. He lived there until 1942, when he was forced to leave Egypt due to ill health. The houses were turned into a museum about 40 years ago. My favorite exhibits are the ostrich egg and the mazwalla [sundial] found in the mosque of Ibn Qalawun, which was used as a watch to announce the time for prayer. I also love the objects that belonged to Gayer-Anderson, displayed in his office, such as his gramophone, typewriter, bottles, personal photographs and a decree from King Farouk. It’s a fascinating window into the past.

Archaeologist Dr. Zahi Hawass is the former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities

Your address: The St. Regis Cairo

Seated at the rustic boardroom table of his studio in the heart of New York’s Garment District, Jason Wu appears calm and relaxed, not at all like someone who has just shown two collections at New York fashion week: a ready-to-wear line for Hugo Boss and his eponymous line, Jason Wu. But don’t let the calm exterior deceive you. This is a man whose drive and ambition saw him designing dresses for dolls as a child in his native Taiwan, a hobby that led to the creation of the Fashion Royalty doll collection, right through to designing the dress that Michelle Obama wore to the 2009 Inauguration Ball, and to his current heady heights as one of the world’s leading designers. That inauguration dress is now in the Smithsonian Museum, which to Wu sums up the scale of his achievement. “When I moved to America to be a fashion designer, I never imagined I’d become part of American history,” he said last year.

Making clothes for dolls gave Wu a grounding not only in the creative side of fashion but also in manufacturing, marketing, intellectual property, business – the many pieces of the jigsaw that make up a successful brand. It was only a matter of time before he would graduate to full-scale frocks. In 2007, at the age of 25, the designer – who had moved to New York seven years previously to attend Parsons School of Fashion – launched his first ready-to-wear collection, instantly catching the eye of the most powerful woman in the fashion industry, U.S. Vogue editor Anna Wintour. “At the time I was starting out there was a lot of streetwear around,” he recalls. “It was a lot edgier than what I do, which is uptown and polished. But Anna and the team were very supportive. It helped me embrace my aesthetic and gain the self-confidence to be different.”

Wu’s description of his signature style as “uptown and polished” certainly hits the mark – no wonder Michelle Obama became a fan. “Having anyone in the public eye support you is instrumental to a brand,” he says, “but when it’s someone like the First Lady, it’s an incredible honor.”

Wu credits his mother, a bestselling author in Taiwan, with teaching him about style and the profound empathy he feels towards women. “I really care about the way a woman feels in my clothes,” he says. “I think that’s very important, because if a dress isn’t about the woman wearing it, what is it about?” Women, in turn, respond to the wearability and femininity of his clothes. Actresses Lupita Nyong’o, Jessica Chastain, Michelle Williams and longtime muse Diane Kruger all wear Jason Wu on the red carpet, and these relationships mean a lot to him. “The idea of red carpet dressing has become so commercialized but we are an independent brand, so for us the relationship is meaningful, not just an endorsement.”

Part of the appeal is that Wu’s clothes are not too aggressively trend-led, which gives them a more lasting appeal. He’s also a firm believer in the value of luxury, talking at length about this much-debated concept. “Luxury isn’t something that only lasts for one season,” he says. “It’s timeless and it takes time to create. I believe we should move away from trying to be the fastest or first – it should be things of substance we invest in.”

Since 2013, while creating his own line, Wu has been a creative director at Hugo Boss, overseeing the entire womenswear range. The appointment was greeted with a certain amount of surprise: after all, Wu’s gowns are all old-school glamour and femininity whereas Hugo Boss has a reputation for streamlined womenswear with a masculine edge. Yet it was that contrast that drew Wu to the project in the first place. “I like the fact that it’s not somewhere people would have placed me,” he declares.

Luxury and elegance, always interpreted with a contemporary sensibility, run through both collections, which is why Wu is drawn to show in spaces that embody these qualities. In the past, he has chosen to show his collections at The St. Regis New York, which reminds him of the 1950s: the era he would most like to return to. “I love it,” he says. “The shape, the clothes: it was a really glamorous time. Not just the fashion, but refrigerators, cars, furniture; the whole thing to me is irresistible.” In fact, after showing at the hotel in 2010 (“It’s so refined – I loved showing my collection in such a landmark”), Wu became an ambassador for the brand – a St. Regis Connoisseur – and has, to date, designed a bag and scarf for St. Regis.

His creative ambitions don’t end there: in addition to designing four collections a year for his own line and four for Hugo Boss, he wants to expand the Jason Wu line, “to really establish a lifestyle brand”. Despite his hectic schedule, Wu did recently manage to squeeze in a family reunion holiday at The St. Regis Bali Resort. “It was great,” he sighs. “The first time we’d all been together in a decade; everyone is just so busy.” Sadly, it may be some time before the next get-together. When asked about his work-life balance, he lets out a rueful laugh. “I don’t have one! But then, I’m not sure any designer would say they do. I’m not too upset about it. My work is my life, it’s my passion. So for now the work-life balance will have to wait.”

Images: Getty Images, Dan Lecca

“What you have to understand is that, for me, map collecting isn’t a casual hobby,” says Nicolò Rubelli, with a laugh. “It’s a disease, an addiction. If I see a map shop, there is no way I can pass it by. I have to go in.”

Rubelli, the fifth generation to run the eponymous textiles company founded by his great-grandfather in 1889, is not only a proud Italian but a proud Venetian. Even as a boy, he says, he appreciated the “incredible privilege” of being one of only about 60,000 permanent residents able to explore Venice’s streets and its bridges, its domes and its bell towers whenever he liked. When, at the age of 17, his father gave him an antique map of the north of Italy, he was hooked. “I loved the idea that, although the map was created in 1648, so much of the city and the area around it still looked the same,” he says. “It gave me a new way of looking at my home.”

For the aspiring architect, who went on to become an engineer, maps were not only a means by which to examine the make-up of the city but to understand the artistic sensibility of that period. “If you look at certain German maps of Venice, for instance,” he explains, “all the bell towers have pointed spires, because the map-makers had reinterpreted the city according to what they thought was beautiful at the time. Most of the publishers in Nuremberg had never been outside Germany, so often the maps they printed were embellished or fictitious – and that’s fascinating.”

Since he was given his first map three decades ago, the company CEO, whose fabrics adorn interiors including Buckingham Palace in London, the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, the Vanderbilt mansion in New York and St. Regis hotels in Rome and Florence, has amassed around 180 maps, printed between 1500 and the late 19th century.

Unlike many collectors, Rubelli doesn’t believe in hiding his printed treasures in drawers or darkened rooms. Each is mounted on white paper so its edge can be seen, then framed simply in wood, and hung “in a giant jigsaw puzzle” in rooms shaded from bright light during the week and opened up for his enjoyment on weekends. One of his most precious maps is also one of the earliest ever printed – in 1500, by Jacopo de’ Barbari. “He went from bell tower to bell tower above the city to draw it, so it’s a perspective view. What’s incredible is that it’s obviously Venice. Certain things aren’t there, like the [Santa Maria della] Salute church, which is beside my house and whose dome I can see from my window. But so much of what we see hasn’t changed at all.”

Today, having run out of wall space, Rubelli tries to buy books of maps (“which are pretty much the same price as single maps”); he has also bought a single terracotta globe, designed by Giò Ponti for porcelain maker Richard Ginori in 1929. “It’s the one exception to my rule, this globe: normally I don’t collect them because they don’t usually feature Venice, they’re overpriced, and I don’t collect 20th-century maps. But I love Giò Ponti’s work, and we have many of his drawings in textiles in our collection. So when I found this at a market in Padua, I just had to have it.”

Images: Contour by Getty

1. 1964, London

When I was seven, my father went to America for six months on a Carnegie grant to lecture about education in Africa, accompanied by my mother. I went to live on my uncle’s cotton and cattle farm in the south of Swaziland, and, at the end of it, they arranged for me to fly on my own to meet them in London. Never having been on a plane before, I was incredibly excited.

2. 1969, Europe

My twelfth birthday present from my father was a family “cultural injection trip” to Europe to make up for the isolation of living in the smallest country in the southern hemisphere. It was incredible: Aida in Rome, the ruins in Pompeii, The Sound of Music in Salzburg, and in London, Hair, Oliver, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Mame, starring Ginger Rogers. I particularly remember in Piccadilly Circus, which was peopled by hippies smelling of patchouli oil, seeing a woman wearing a transparent blouse. As a little Swazi boy in shorts, my eyes were on stalks!

3. 1978, London

This trip was my twenty-first birthday present from my parents, when I was midway through my drama degree. In six weeks, I saw 72 plays and films, including Judi Dench and Ian McKellen in Macbeth – both of whom I would work with 15 years later in Jack & Sarah. I diarized everything I saw and knew in my bones that this was the city in which I wanted to spend my adult life.

4. 1982, London

After my father’s death at the age of 52, I emigrated to England with a couple of suitcases, a Sony Walkman and big dreams. I lived in a tiny bedsit in Notting Hill Gate and worked as a waiter. Having met my future wife, Joan Washington, who coached me to do an Irish accent, I got an agent and began to get work: Shakespeare in Regent’s Park, then an improvised TV film for the BBC with Gary Oldman, which led to me being cast in Withnail & I and ultimately gave me a film career.

5. 1987, Los Angeles

I was flown to the U.S.A. to film Warlock. The excitement of being in Hollywood was matched by the acute loneliness of landing in a city where I didn’t know anyone and where you had to drive everywhere. Julian Sands introduced me to Jodie Foster, while every agent I met told me they were “so excited!” – something I soon realized they said to everyone, about everything. Working in bright sunshine in the middle of the Californian winter was spectacularly seductive, as was going to the grocery store and seeing screen legends I’d grown up watching in the cinema.

6. 2004, Swaziland

After five years of script rewrites, financial hiccups and casting challenges, I called “action” on my autobiographical film Wah-Wah, all shot in locations where the key events had actually taken place. It was a journey back into my own lifetime, and both cathartic and surreal by turn. I was particularly struck by the symmetry of having made a shoe-box theatre with cut-out figures attached to lollipop sticks when I was a little boy and then watching – on a monitor the same size as a shoe box – the story of my life being filmed with great actors like Gabriel Byrne, Emily Watson and Julie Walters.

7. 2012, Grasse

Handbag supremo Anya Hindmarch saw me sniffing everything in sight on holiday in Mustique and suggested I create my own perfume. Visiting the olfactory nirvana of Grasse had been a lifelong dream, and the perfumed air when I arrived at the flower distilleries made me feel like Charlie stepping into the Chocolate Factory. I’d tried to make scent when I was 12, to impress an American girl, but my attempts at boiling gardenia and rose petals in sugar-watered jam jars failed. Fast-forward four and a half decades and choosing oils in Grasse to conjure up the scent I’d long dreamt of bottling was a Eureka moment. Jack (jackperfume.co.uk) launched in 2014, combining lime, marijuana and mandarin notes: my signature in scent.

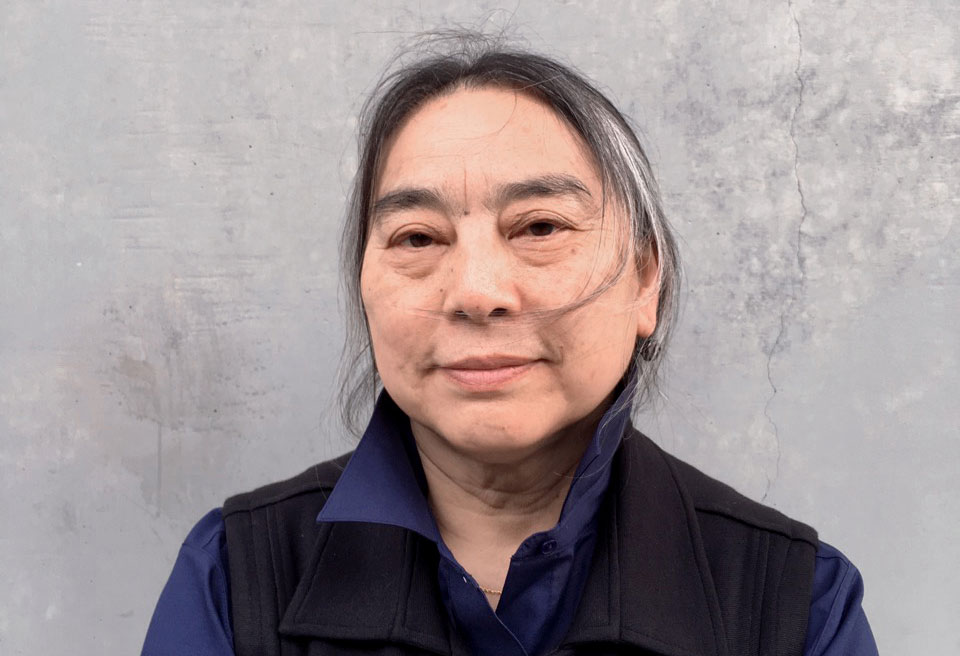

In a visionary body of work, rich in symbolism and pathos, California-based artist Hung Liu connects history to the present, East to West, mundanity to beauty. Dripping with immediacy, as if the artist has just put down the brush, her paintings of anonymous figures adapted from historical photographs are timeless, yet paradoxically anchored to the past, infused with a nuanced narrative and layers of psychological insight.

Born in China in 1948, Liu came of age during the Cultural Revolution. After high school, she was sent to the countryside where she spent four years working in the fields. There, she photographed and drew workers and their families. This was a formative experience for the young artist, who went on to portray ordinary people as the subjects of much of her work.

Following her early studies as a mural painter at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, one of China’s leading art schools, in 1984 Liu emigrated to America to pursue a graduate program in visual arts at the University of California San Diego. Today, from her hometown of Oakland in California, she re-contextualizes snippets of history that may not be lost, but have perhaps been forgotten. “I’ve come to think of these subjects as ghosts I ‘summon’ from the grainy, chemical surfaces of the photographic past,” she says. “That’s kind of going backwards technologically, from a newer medium to an older one, but mineral pigments on canvas can be very physical, bringing the image forward into the present in a vivid, present-tense way. There’s some kind of alchemy here, although I think of myself less as an advocate or guardian, more as a witch.”

On a visit to China in 1991, Liu found a treasure trove of studio photographs of 19th-century Chinese prostitutes, which became references for a series of riveting multimedia works. A series called Dandelions, meanwhile, is based on photographs she took on a road trip, the flowers often blown up to the size of the human figure. And the subjects of American Exodus, on show this fall at the Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York City, are based on images of migrants from America’s Depression era that she found in the Dorothea Lange archive at the Oakland Museum of California.

In a Wall Street Journal review of her 2013 Oakland Museum of California retrospective, Summoning Ghosts: The Art of Hung Liu, critic David Littlejohn referred to Hung Liu as “the greatest Chinese painter in the U.S.”. Her art, which is represented in the permanent collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, not only mirrors the unique duality of her extraordinary life experience, straddling two cultures, but transcends the boundaries of time.

Hung Liu: American Exodus is showing at the Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York City until October 22, 2016

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Crane Dance, 2011

The delicate cloud of circling cranes in this work has a profound underlying significance. “In China, cranes are considered auspicious, and are associated with the imperial palace and heaven,” says Hung Liu (below). “This woman is from a photo, circa 1865, by the American John Thompson. The juxtaposition of her hand with the cranes suggests the vast space between the imperial court and working peasants.”

Dandelion 11, 2015

“The woman and the flower are both ornamental, but the dandelion is mostly blown away. It suggests to me the unpredictable course of one’s life, no matter how ornamented one is,” says Liu.

Widely regarded as one of the top chefs in Italy, Valeria Piccini’s restaurant, Da Caino, in southern Tuscany, has held two Michelin stars since 1999. Three years ago, Piccini was invited to team up with The St. Regis Florence’s executive chef, Michele Griglio, to create Restaurant Winter Garden by Caino, the hotel’s fine dining experience, housed in an exquisite former courtyard with lofty ceilings and sumptuous décor. From day one, the collaboration between these two culinary masters has been a resounding success: in 2014 the restaurant was awarded a Michelin star for its unique take on classic Tuscan cooking.

What do you eat when you’re home alone?

V.C. Spaghetti and eggs with tomato sauce.

M.G. Something very simple like a beef fillet.

What would you order from the menu at Restaurant Winter Garden by Caino?

V.C. Right now I would order the homemade ravioli stuffed with grey mullet on a cream of fresh peas and grey mullet roe.

M.G. For the ultimate experience you really have to try the tasting menu.

What’s your favorite dish to cook?

V.C. Definitely pasta and desserts.

M.G. Spaghetti with tomato sauce.

Are you inspired by local ingredients or traditions?

V.C. Always. We try to use local products as much as possible. For example the grey mullet and the grey mullet roe both come from Monte Argentario [a peninsula off the southern Tuscan coast].

M.G. I’m constantly inspired by Tuscany’s incredible culinary tradition and all the outstanding products the region has to offer.

What’s been your proudest or most memorable moment during your career?

V.C. When I was awarded a second Michelin Star at Da Caino. And when we received our first Michelin star at Restaurant Winter Garden by Caino.

M.G. In 2005, when I did my first service alone [as head chef], in charge of an entire kitchen staff.

Which dish you’ve created are you most proud of?

V.C. It’s impossible to choose just one. My favorites are tortelli pasta with Cinta Senese [a type of pork], tortelli with cacio cheese and pears, and I always love cooking anything with pigeon, because for me it’s the best meat.

M.G. I’m very proud of my risotto with peas and squid.

What’s the best thing to eat in Florence?

V.C. Lampredotto, which is a traditional Florentine dish made using part of a cow’s stomach, boiled in a broth with tomato, onion, parsley and celery.

M.G. You can’t beat a Florentine steak.

If you could revisit any meal in your life, what would it be and why?

V.C. It has to be lasagne – I love it.

M.G. I’m a big fan of jerk chicken, a typical Jamaican dish. One day I would love to recreate it with a touch of Italian style.

What’s the secret to running a restaurant?

V.C. Never losing the passion you had at the beginning, constant research, and humility, which I’ve noticed seems to be decreasing.

M.G. I’m still trying to find out, but passion and constant dedication are without doubt the starting points for a successful restaurant.

When you were a child, what was your favorite type of food and do you still eat it now?

V.C. For me it was always pasta with butter and Parmesan cheese, but to be honest I don’t eat it very often these days.

M.G. I always loved dark chocolate. It’s one food I’ll never give up.

Which dish or meal most reminds you of home?

V.C. I’ve always had a nostalgia for foods that are derived from the cheese-making process. My parents were dairy farmers, so I always loved eating “cuculo”, which is the spun curd before it becomes cheese, and “scottino”, a combination of hot ricotta cheese, buttermilk and bread.

M.G. Sunday roast beef always makes me think of home.

Your address: The St. Regis Florence

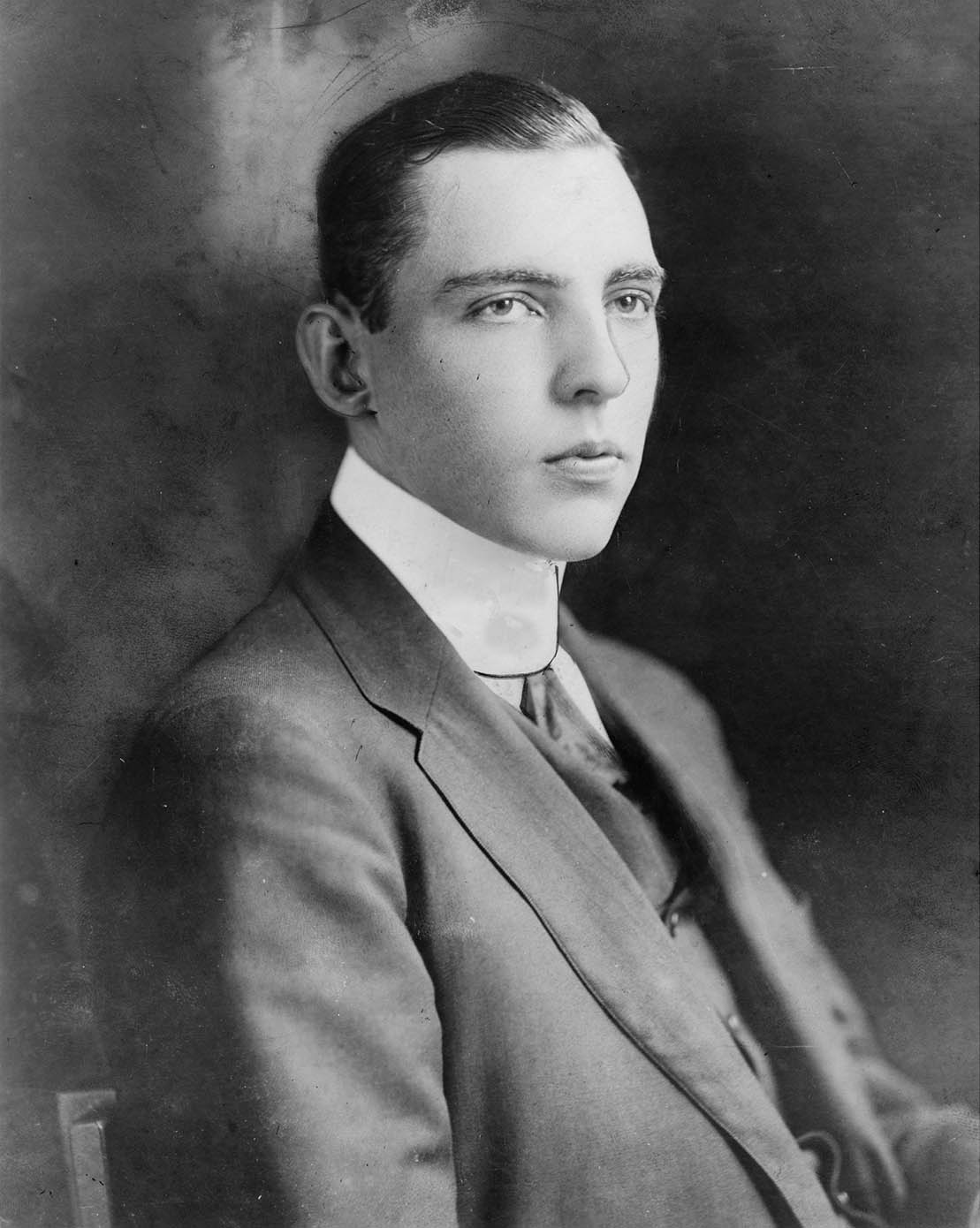

Every day, from when he was 20 years old, Vincent Astor slipped into his pocket the most valuable thing he owned: the watch used by his father, John Jacob Astor IV.

While personal heirlooms are normally of sentimental value to bereaved children, this watch was particularly precious. John Jacob had been one of the nation’s wealthiest men, and one of New York’s most keenly chronicled social figures, and the watch was in his pocket when he boarded the Titanic in Southampton with his young (second) wife, Madeleine, in 1912. Although Madeleine survived, John Jacob perished, and when his body was retrieved from the freezing waters and taken back to New York, the gold watch that had been in his pocket beneath his life jacket was presented to his son. It was never recorded whether the pocket watch still kept the time or if its hands were stilled, or even whether its numerals were still readable, having been immersed in water for days. But it remained in Vincent’s pocket for the rest of his life.

The two men had been extremely close. As the biographer Justin Kaplan writes in his book When the Astors Owned New York, “Vincent adored him and was adored in return”, obliquely referencing Vincent’s mother, Ava, who was unadoring, if not hostile, to both men. “Jack spent much of his time away from Ava in the company of their son... he was happiest sailing with Vincent on board Nourmahal, the steel-hulled steam yacht he had inherited from his pleasure-loving father.”

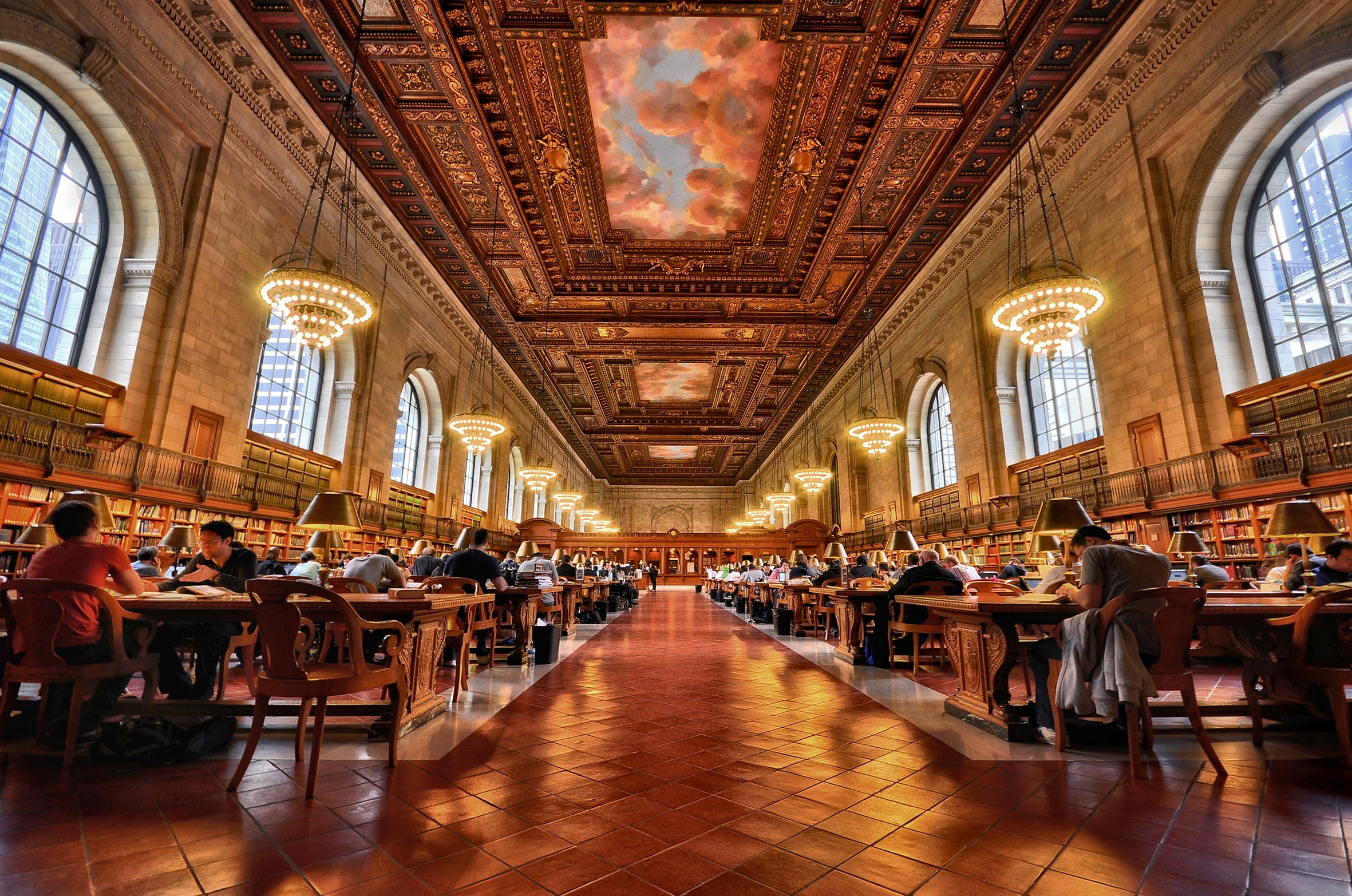

With the sinking of the Titanic, everything changed in Vincent Astor’s life. Having been a carefree undergraduate at Harvard, he suddenly became “the richest young man in the world”, with enormous responsibilities – and an empire to run. Alongside his father’s precious timepiece, $87 million cash and vast swathes of New York real estate, one of the most valuable items Vincent inherited was the St. Regis Hotel in New York City. An elaborately wrought and technically advanced building opened by John Jacob in 1904, it was, according to Frances Kiernan, an Astor biographer, “one of his proudest assets”.

There was much about the St. Regis Hotel to be proud. Architecturally, the Beaux Arts–style edifice was celebrated as much for its expertly articulated ornamentation as it was for the state-of-the-art engineering. As Robert A.M. Stern describes it in his book New York 1900: “The St. Regis [was] an accomplished design that used a vocabulary of ornamental details based on contemporary French practice to set a new standard for the luxury hotel.” The hotel’s general manager Rudolf M. Haan, wrote at the time of the opening of the 18-story hotel at Fifth Avenue and East 55th Street: “My hotel is not a place for billionaires only, but a hostelry for people of good taste who have the means to live as comfortably as they choose.” And the critic Arthur C. David said in a 1904 issue of Architectural Record that the elegance, grandeur, and domestic feel of the city’s finest townhouses “have been transferred to a hotel, and have in some respects been transcended”. He added that those who gravitated to the hotel were taken with the fact that it was “somewhat quieter and more exclusive” than other fashionable hotels.

When the hotel was first built, it was situated in what was then a decidedly upscale residential neighborhood, but was, as Arthur David put it, “plainly withdrawn from the ordinary places of popular resort”. By the time Vincent had inherited the hotel, however, it was a locus of New York society life, and its very existence had transformed the surrounding neighborhood into the city’s premier shopping area. Nevertheless, for reasons that remain unclear, Vincent sold the hotel to industrialist Benjamin N. Duke, who added the famous St. Regis Roof, with its elegant, frescoed dining room, and the Salle Cathay, both of which played host to some of the era’s most prestigious parties. By the early 1930s, however, Duke had allowed the hotel to lose its sparkle. In 1935, Vincent Astor regained control of the property through a mortgage default and immediately set about returning the St. Regis to its former glory. He modernized it, hiring the highly respected Anne Tiffany to redecorate, and made it financially profitable within just two years by placing his brother-in-law, Prince Serge Obolensky, on the executive board. La Maisonette Russe (formerly known as The Seaglades) became one of the most popular supper-nightclubs in New York. The Roof was turned into The Viennese Roof. The Iridium Room replaced the Salle Cathay and swiftly became one of the city’s hottest spots, complete with an ice-skating platform that rolled out from beneath the orchestra floor.

The hotel was a source of immense pride for Vincent. Although he was never a handsome man – who dressed in rather unimaginative suits, and was described by his mother as “stupid” as well as “clumsy and lumpish looking, with big feet” – he certainly understood the beauty of impressive buildings. He owned exquisite homes in Bermuda, Phoenix, Rhinebeck in upstate New York and Northeast Harbor, Maine – many of them considered among the finest houses in America. In the city, the building at 120 East End Avenue in which he lived with two of his three wives in the 23-room penthouse was considered one of the most luxurious apartment blocks of its day. But the most coveted of all of the homes he owned was a Manhattan townhouse he’d commissioned in 1927. The Regency-style townhouse on East 80th Street (now the headquarters of the New York Junior League) was so deep that it ran the full length of the lot to 79th Street and incorporated both a sunken garden and garage. It was, according to Robert A. M. Stern in his book New York 1930, a masterpiece, whose plan was “exceptionally gracious” and whose individual rooms were “delicately scaled”.

Real estate was in Vincent’s blood, and as well as creating beautiful homes for himself, he created vast housing projects across New York. Recognizing the increasing demand for upscale residences in Manhattan, he began to transform entire neighborhoods with new buildings, many of which still exist today. On East End Avenue, for instance, at the corner of East 86th Street, he erected fashionable and handsomely appointed Georgian-style apartment houses that still remain stolid fixtures in the neighborhood. Working together with Obolensky, he converted a row of Victorian-era brownstones between 88th and 89th streets into something he fondly referred to as “Poverty Row” (a reference to the fact that he envisioned young artists and professionals moving in who hadn’t yet made their fortunes in life, but would).

Not all of his life, though, was taken up with business – or mixing in high society. In fact, in marked contrast to his grandmother, who had established “The Four Hundred”, a collection of 400 members of American high society, Vincent was drawn to charitable rather than social causes. Despite the fact that John Jacob Astor, Vincent’s great-great-grandfather, had been one of the founders of the New York Public Library, the Astors were not especially famed for their civic or social generosity. In fact, prior to Vincent’s involvement, many of the apartments controlled by the family had devolved into slums – something the young man set about trying to put right.

By 1935, he had become instrumental in establishing America’s first managed housing project. Having sold a significant parcel of the Lower East Side to the New York City Housing Authority for less than half its market value, he built eight five-story walk-up apartments, meant to house poor and working families, many of them immigrants. On East 79th Street, he constructed housing for working people that, for the first time says David Patrick Columbia, co-founder of the New York Social Diary, took into consideration their health, “being constructed near water, with fresh air and ample space around them. He was sensitive in that way, very involved.”

Alongside housing projects, he funded youth projects at the New York Hospital and the American Red Cross, set up playgrounds and youth centers around the city, and built the Astor Home for Children in Rhinebeck, N.Y. “During his own childhood he was mistreated by his mother,” Columbia says. “So, as an adult he became extremely sensitive to the needs of children who were mistreated and needed love and attention.”

Given his relationship with his mother – and the fact his father’s second wife was only a year older than Vincent – it is hardly surprising that his private life was less successful than his business life. A man not known for natural bonhomie, nor interested in the activities required of his class, Vincent preferred to spend time sailing on the yacht he commissioned in 1927, a new Nourmahal, named after the vessel on which he and his father had passed such happy times. The 264-foot yacht, which he later donated to the U.S. Navy during World War II, boasted eleven staterooms, a dining room for 18 and a crew of 42. With its cruising range of 20,000 miles, the yacht allowed Vincent to travel the world for months at a time, even bringing home tortoises and other exotic specimens he found during his trips to the Galapagos and donating them to the Bronx Zoo. Back on dry land, while his successive wives continued to socialize at galas and fashionable functions, the biographer Kiernan notes that “Vincent went to the office every day. And when night came, he was a virtual recluse, wanting nothing more than to enjoy his dinner and relax by the fire.”

Of his three marriages, his last, to Brooke Astor in 1953, was perhaps the most successful. Unconventionally, the match had been set up by his second wife, Minnie. Vincent and Minnie’s marriage had long been over, but she agreed to divorce him only when she could find him a suitable wife. When Brooke’s previous husband died in 1952, Minnie arranged a dinner party, seating the widow opposite Vincent. Within weeks he had proposed.

By then, so astute was Vincent as a businessman, he had already doubled the family assets and initiated several notable ventures. One of these included providing the funds to merge Today magazine with a then defunct publication called Newsweek, to create a more politically progressive foil to rival Time. He became the famous magazine’s chairman from 1937 to his death in 1959. But perhaps his most dramatic and lingering financial undertaking was his establishment of the Vincent Astor Foundation in 1948, the goal of which was simply “the alleviation of human misery”. It was a big motto to uphold, but if any charity has come close to realizing that goal, it has been this foundation.

After his death in 1959, Brooke inherited $67 million to give to charitable causes: half the value of the estate. Until it was all spent in 1997, funding was given to countless institutions small and large: to dance troupes, the New York Public Library, neighborhood literacy programs, the Bronx Zoo (which built its monorail, among other features, with the grant money), the restoration of Bryant Park in midtown Manhattan, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Corporation, and the installation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Astor Court, a full-scale replica of a traditional Chinese garden and house.

Today, Vincent Astor’s legacy is present in so many aspects of New York life that the city would be unrecognizable without his munificence. Not only did he build neighborhoods that are mainstays of Manhattan and fund many of the city’s key cultural institutions, he also helped children gain access to good housing, recreation and education.

It is more than ironic that one of Vincent’s first heart attacks occurred as he was entering a theater in Poughkeepsie, New York, to attend a screening of A Night to Remember, a feature film that depicted the Titanic disaster. The story of his extraordinary life had come full circle.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Images: Getty Images, Pars International/Newsweek, Rex Pictures, Mary Evans Picture Library, Alamy