Around Aspen, the term “heavy metal” is not bandied about lightly. Here, it does not mean that Judas Priest is in town for a set, although of course this little town in the Rockies attracts more than its fair share of big music acts, both to perform and to enjoy some downtime. Nor is it a reference to high-carat bling at the Golden Bough jewelry store, though Aspen is one of the wealthiest spots on the planet. Or to the 2,350lb silver nugget pulled from the Smuggler Mine in 1894, during the town’s early prospecting days, when Aspen was a place where people came to find their fortune in the newly-discovered silver lodes, rather than to enjoy it. No, around Aspen, “heavy metal” chatter means that the Aspen/Pitkin County Airport is gearing up for a steady stream of A-listers jetting into town. Known locally as Sardy Field, the airport is one of the busiest small airports in the country. Fleets of GulfStreams, Challengers and Citations can fly in on any given day, especially for the Fourth of July or New Year’s Day. At the same time $20 million trophy homes in the elite Red Mountain neighborhood are being primped and polished, likewise those lovingly restored “painted lady” Victorians in the historic West End. And across town, chefs, personal assistants and private shoppers are put on high alert. Invitations go out from Aspen’s high-society hostesses (Ivanka Trump, Glenda Greenwald, Soledad Hurst, Paula Crown) for everything from big charity bashes to “cosy” suppers feting a visiting artist or media mogul.

What is it about this luxe little town in the Colorado Rockies that inspires such an influx? “Aspen is like no other place,” says local real estate broker Joshua Saslove of Joshua & Co., part of Christie’s Great Estates international network, who has been accommodating the whims of a moneyed and powerful clientele for more than 20 years. “The wealth of the world is drawn here not only for its natural resources, but for the character of the town, its passion for intellectual activity and its cultural amenities.” Proximity to all of the above doesn’t come cheap. Indeed Aspen is one of the most expensive real-estate markets in the USA, with people paying “a lot of money for city penthouses with views. Up here at this altitude, we have a 7,000ft advantage.” A veritable who’s who of famous faces (Kevin Costner, Goldie Hawn), tech wizards (Amazon’s Jeff Bezos), media moguls (Michael Eisner) and corporate billionaires (Charles Koch, Roman Abramovich, Stewart and Lynda Resnick, Sam Wyly) have added big-ticket properties to their portfolio of homes.

Aspen got its first real taste of wealth in 1879, when silver prospectors flocked here to the summer hunting grounds of the local Ute Indians to mine the recently discovered silver lodes. During this boom time, the area’s mines produced nearly $100 million worth of silver ore. Aspen’s next boom was the result of another valuable product of Mother Nature: snow. In 1947, the Aspen Skiing Corporation cranked up the mountain’s first chair lifts and, three years later, the FIS World Skiing Championships packed the town with celebrities and Olympic skiers. Aspenites and visitors alike rejoiced by riding horses into bars and Aspen Crud (a milkshake laced with bourbon) flowed like water. The town’s reputation as a world-class ski – and party – town was set.

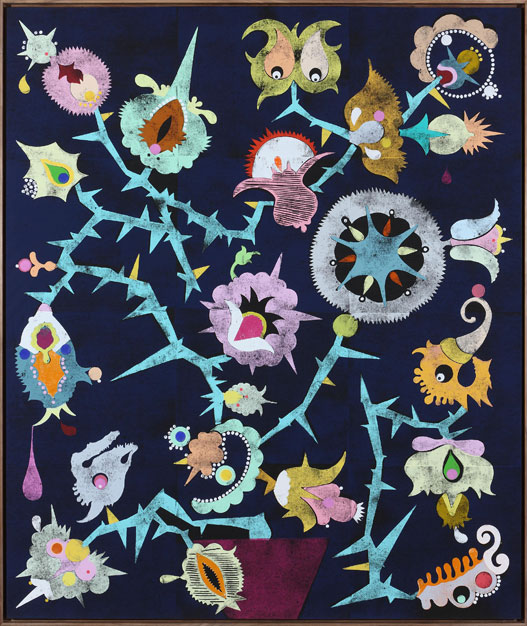

Right from those early days however, intellectual ambition was a key part of the Aspen mix. In 1945, the Chicago businessman Walter Paepcke visited the Bauhaus architect Herbert Bayer in his minimalist home outside town. Together they discussed how to make the resort somewhere artists and thinkers could gather to exchange ideas. Paepcke proved adept at attracting both generous sponsors and cultural heavyweights to his endeavors, and he quickly launched the Aspen Institute, the Aspen Center for Physics and the Aspen Music Festival. The Festival continues to attract major performers and music fans every summer, and while the Institute’s HQ is now in Washington DC, in 2005 it spawned the Aspen Ideas Festival, helmed by Walter Isaacson, which aims to stimulate debate with a series of talks and forums attracting global opinion formers such as the Clintons, media entrepreneur Arianna Huffington and author Thomas L. Friedman. All of which means that, like Davos in Switzerland, today Aspen can claim to be as much about cultural or “thought leadership” as it is about great runs. What’s more, given all of that cultural ambition, the wealth, and the fact that some of the world’s leading collectors have homes in Aspen, it should come as no surprise to hear that there is also a concentration of high-end galleries here.If Calders and Lichtensteins are to your taste, they can easily be found at Casterline Goodman Gallery.

If you’re after a Ross Bleckner painting or a Bruce Weber limited-edition print, then perhaps you should head over to the Baldwin Gallery. Or for the kind of fine art collectible that can be shipped home effortlessly, Pismo Fine Art Glass will have a Chihuly or two. Meanwhile, the ultra-contemporary, 30,000 sq ft Aspen Art Museum, designed by Shigeru Ban and under construction in the heart of downtown, has benefitted from some starry fundraising events (most of its $65 million cost has been privately funded). Culture aside, the extraordinary setting of Aspen remains core to its appeal. In summer, a seemingly endless chain of back-country trails beckon for hiking, mountain biking and horse riding, and there are trout-filled waters, where rafters and kayakers can also get their kicks. In winter, naturally, you can enjoy some of the best skiing in the world – on four distinct mountains – plus of course that après ski: the private mountaintop parties up at the cosy Cloud Nine Alpine Bistro on Aspen Highlands or the champagne bar of the private Caribou Club. Less exclusive, but sometimes even more fun, there is a buzzing live music scene at venues like the famous Belly Up, or Music on the Mountain concerts on Aspen mountain. Then there’s the food.

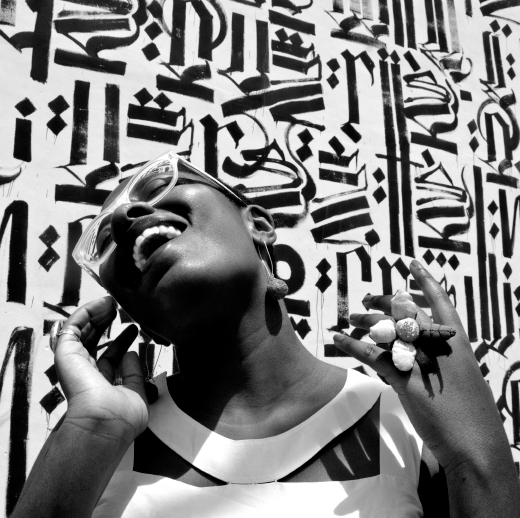

If Cloud Nine’s appeal is homey Alpine cooking, elsewhere, Aspen also has one of the most competitive restaurant scenes in the United States – from the freshly sourced sushi Robert De Niro enjoys at Matsushisa to the ever-changing menu of the Chefs Club at The St. Regis Aspen Resort. There, innovative dishes by up-and-comers from Food & Wine magazine’s Best New Chefs program are whipped up by executive chef Didier Elena, who has spent the past 20 years working alongside the world-renowned Alain Ducasse. For Didier, the opportunity to come to Aspen was too much to pass up. “Aspen is unique,” he says. “People from all over the world come here to live, to enjoy this place – and to eat.” Naturally Aspen’s year-round enthusiasm for all things foodie is reflected in yet another major festival, the popular Food & Wine Aspen Classic every June. It is worth noting, though, that despite its fancy restaurants and lively social scene, Aspen isn’t a town for Manolos. Heels do not mix well with cobblestones, and though furs are worn year-round, the billionaires who own those modernist penthouses and exquisite 19th-century houses are often to be seen wearing cowboy boots.

Curiously, one man who spotted Aspen’s potential early on also played a major role in the making of Utah’s Deer Valley Resort, another globally-recognized ski destination. The New Orleans real-estate entrepreneur Edgar Stern developed Aspen’s first gated enclave, the 1,000-acre Starwood. Over the years, Starwood has been home to many famous residents, perhaps the most celebrated of all being Country music legend John Denver, who referenced his idyllic 7-acre property in many of his songs. Stern then followed his instincts to Utah’s Wasatch Mountains. After scouting around the rough-and-tumble Park City Ski Resort, and eventually purchasing it and the acreage around it, he initiated the concept of a top-notch ski resort operated like a 5-star hotel. Deer Valley Resort is all that and more. Like Aspen, it’s on the radar of the country’s upper crust, who fly in to rub shoulders with an international collection of likeminded revelers in luxe hillside homes. Also like Aspen, it’s a delightful summer destination, especially for those with a proclivity for outdoor adventure, gallery-hopping, or performances at an outdoor amphitheater during the Deer Valley Music Festival, which is the summer home of the Utah Symphony and Utah Opera.

For, just as in Aspen, high culture is also a key component of Deer Valley’s appeal – for many visitors, as important as the mountains. Each January, the streets are studded with Hollywood’s finest, up for the annual Sundance Film Festival, a launching pad for independent films. Between screenings, stars gather at Robert Redford’s Zoom for chef Ernesto Rocha’s wood-fired artichokes and steak frîtes, or at Bill White’s Grappa for lobster ravioli and osso bucco. March brings a week-long fête called Red, White & Snow, with ski-in wine-tasting events on the slopeside Astor Terrace at The St. Regis Deer Valley. Of course Aspen and Deer Valley have their partisans. But as tempting as it may be to join in the bacchanalia of high season in the high country, local knowledge in both destinations has it that it is the days after the lifts close, or when the golden aspen leaves have fallen, that can be the most rewarding. Perhaps the most special time to capture the essence of America’s mountain playgrounds, then, is when you can have it all to yourself.

Your address: The St. Regis Aspen Resort; The St. Regis Deer Valley

Images by Denver Post via Getty Images, 4 Corners, Rex Features