Artisans have always been the heart and soul of Italy. Although “haute couture” began in Paris in the early part of the 20th century, the great Italian ateliers emerged on the international stage in the 1950s thanks to the fashion pioneer Giovanni Battista Giorgoni. The entrepreneur cleverly persuaded US buyers to stop in Florence the day after the Paris collections, before flying back to America. Both buyers and press returned home inspired by what they saw, and Italian “alta moda” (or couture) was born. Three talented sisters, the celebrated Sorelle Fontana, led the way, the glamour of cinema immortalizing their designs in the public imagination when they unforgettably dressed Ava Gardner in The Barefoot Contessa and Anita Eckberg in La Dolce Vita.

Giorgini cemented Italy’s fashion reputation internationally, and when he stopped hosting shows in Florence, Rome gradually took over. Galitzine, Lancetti, Fausto Sarli, Renato Balestra and Raffaella Curiel were among the many prestigious houses – the greatest though, were Valentino Garavani and Roberto Capucci. Both equal in genius in the pursuit of beauty, Valentino was more commercial and international, while Capucci, who never ventured into prêt-à-porter, was more known at home than abroad, memorably dressing Italian socialites in fantastical sculptural creations. With the rise of Italian prêt-à-porter, led by designers such as Walter Albini and Giorgio Armani in the 1970s and 1980s, Milan gradually eroded Rome’s position and turned the spotlight on itself.

But today, there is a renewed focus on AltaRoma, as the assembly of Italian couture houses is known, showing twice a year in January and July, immediately after the haute couture shows in Paris. Currently under the stewardship of Silvia Fendi, the doyenne of celebrated Fendi accessories such as the Baguette bag, and granddaughter of the legendary house’s founders, its aim is to promote and sustain the extraordinary wealth of Italian artisanship passed down through the centuries. “AltaRoma has a specific vocation – that of treasurer of our artisanal heritage,” Fendi says, “as well as being a launch pad for innovative, creative people seeking to develop their international profile. Rome is now a scouting centre for global talent.” With the support of Vogue Italia editor Franca Sozzani, the best young designers are being discovered through the competition Who’s Up Next? Today, former winner Sergio Gambon is the creative director of Galitzine, and is one such talent continuing the tradition of haute couture in Rome. Most of the “hands” – as the top-level seamstresses are known – learned the craft at their grandmothers’ knee, sewing dresses for their dolls.

Witnessing these unsung artisans at work in ateliers across Rome is enlightening and humbling, like observing the weavers of 15th-century tapestries. The care, precision and expertise given to each stitch recalls a true artist at work, and to know that this craft is being kept alive in a world of accelerated change, is a vital connection to the past that safeguards the integrity of haute couture.

Your address: The St. Regis Rome. A private visit to the Fendi atelier, design studio and boutique can be arranged for guests.

Valentino

Since Valentino’s legendary 1968 White collection knocked the fashion world sideways, he has been at the epicentre of Italian couture. Jackie Kennedy gilded his reputation when she ordered a wardrobe of clothes for her official mourning period as JFK’s widow. Later, the picture of her white-lace mini-dress for her wedding to Aristotle Onassis in 1968 became an iconic image. Many of the house’s premier seamstresses have been working there for decades, and some have memories of fitting Kennedy and Audrey Hepburn.

Neighbouring rooms with glass doors overlooking the Piazza di Spagna are furnished with large tables at which six or seven seamstresses work under the eagle eye of a premiere. Photographs of some of the world’s most famous women, wearing dresses made within these very rooms, occasionally interrupt the whitewashed walls. Powerful neon ceiling lamps illuminate the workshop, and metal irons of different weights are neatly stacked on shelves. The ladies at the table are currently working on the top-secret haute couture collection to be presented in Paris in July.

In one small room, four focused young seamstresses and one young man, all with pin pouches attached to their chests, painstakingly embroider a landscape on a single black sheet of tulle. It’s utterly beautiful, reminiscent of an ancient Chinese pen-and-ink drawing. But this, I learn, will only be one of the four layers of the finished dress.

In another larger room, several “hands” are constructing delicate flesh-coloured bustiers. It’s exhilarating to see exactly what’s behind each item of clothing: the geometry, the imagination, the skill, patience and dedication afforded to every single hand-sewn stitch. Some dresses are first made in paper, then in fabric. Each part of the craft is complex and demanding because they are unique pieces, but perhaps the hardest part is to achieve the perfect “drop” of the dress.

At Valentino, different “hands” are needed to handle different fabrics, but the current creative directors of Valentino, Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli, are known to sometimes use a seamstress who, say, usually works with lace, to drape leather.

The dresses produced here are one-off pieces and when Valentino has a “bestseller”, it means that just three editions of the same dress are made.

Tommy e Giulio Caraceni

This celebrated sartoria, founded in Rome by Domenico Caraceni (1880-1939), has dressed Italy’s most dashing men for generations. The legendary Fiat boss, Gianni Agnelli, was a regular customer. “I was taken on full time to make his suits,” explains master-cutter Giancarlo Tonini, who has worked at the same table for 53 years. “He would bypass the fitting room, head straight to where the tailors were at work, sit on the edge of a counter and talk football with them.” When Gary Cooper had a breakdown in 1931, he left Hollywood for a year of travelling in Europe and big-game hunting in Africa. He stopped at Caraceni to get suited up, marking the beginning of his reputation as Hollywood’s best-dressed man.

Tonini points out the particular trait that makes a Caraceni suit instantly recognisable: the top buttonhole remains unused and exposed on the lapel of the jacket. “There are those who always want the same fabric,” continues Tonini, “like the incredibly smart Count Cini, and those like Agnelli, who tried everything. Agnelli had his own style.

Still, today, customers arrive with photographs of him, asking me to make them the same suit.” Tonini is currently making a blue pin-striped suit, which will take him a minimum of three weeks to complete. The customer’s measurements are drawn out on brown packing paper and spread onto a three-meter counter where the fabric is cut to size. “The only thing done by sewing machine are the hips, the back stitch, and the exterior of the sleeves – the rest is sewn by hand.” “Sadly, new ‘hands’ are few and far between in this craft,” explains Guido Finigalia, who manages the business. Tonini, the slim 75-year-old master tailor, impeccable in his Caraceni suit, is more pensive: “When Italy loses its artisanship, it will lose its history.”

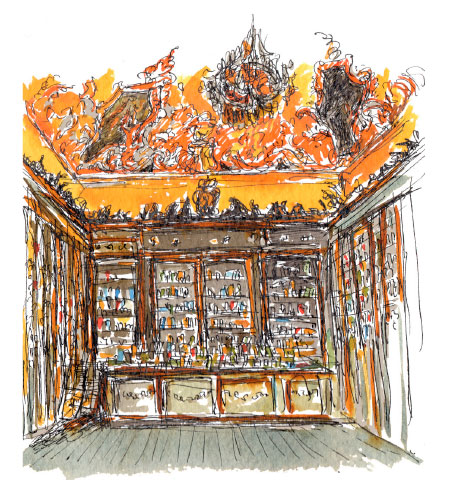

Antica Cappelleria

In 1935 the Cirri brothers from Florence opened the Antica Cappelleria in the heart of Rome, in the days when society demanded diligence in gentlemen’s and ladies’ clothing. The Cirris worked and slept on the premises. “Hats are an incredible form of communication as well as objects of seduction,” says the current owner Patrizia Fabri. “Just look at what a crown symbolizes.” Fabri bought her first hat at this very shop when she was 18 in the early 1980s. “I bought a straw hat, decorated it myself and sold it on immediately. I went back the next day and ordered 25 more, took them around to fashion stores and got more orders.”

Born from this enterprising spirit, Fabri had her career cut out for her. So when the Antica Cappelleria was about to go out of business in 2003, she took over and saved the day. The atelier reverberates with her enthusiasm for the craft. “The first bashing the hat got was in the 1920s with the advent of the motorcar,” explains Fabri, “and then later and more severely in the 1970s due to feminism.” The premises are stacked with elegant hats in all shapes colours and sizes. They are custom-made in the back room by master hatter Sandro Bellucci. “I started by chance at 14 and never looked back,” he says, while steaming a hat made from rabbit hair in a dome-shaped, cast-iron oven. “The raw material as a rule for all hats is rabbit fur because it’s water repellent. It’s then treated so it can be dyed and shaped.”

Above us on surrounding shelves is an infinity of wooden hat molds from different eras that Fabri travels the world to collect for her archive. “We’re determined to maintain traditions unaltered through time,” she says passionately. “There is only one producer of raw materials for hat-making left in Portugal, otherwise one must order now from China.” Fabri has made hats for many designers, including the great Roberto Cappucci for an exhibition currently being shown in Beijing. Handmade top hats and panamas are suspended above our heads. Here a customer can come in, be measured up, choose a hat for day or evening and have it on their head before close of business. Fabri slips on a 1920s cloche, looking as though she were born in it. “A person has a good relationship with a hat when they feel as though they’re not even wearing one!” she laughs.

Renato Balestra

A former engineering student and pianist, Renato Balestra is especially known for his fabrics, hand-embroidered in his basement atelier, and for Blu Balestra, a particular tone of peacock blue that he has always been passionate about and uses in each of his collections. Famous clients include Farah Diba of Iran and the Queen of Thailand.

Angela, the premiere, has been working for him for 20 years. She learned the craft from the age of six at home. “It’s difficult to find new ‘hands’,” she says. “I think one can only do this job out of passion.” At the next table, Chiara is doing embroidery. Being a new “hand”, she studied at the Accademia in Rome.

Once a dress has been ordered it takes around 20 days to complete. Balestra, now 88, is still closely involved with every aspect of his collection. “Haute couture is a whole culture, an art,” he says.