Once seen, a Beatriz Milhazes canvas is never forgotten. The 54-year-old Brazilian’s palette races through tangy citrus, raspberry, blueberry, coral, mint, scarlet and sky-blue. Sharpened here and there by linear shapes, the leitmotif is the sphere, often figured as a tropical flower. But she explodes the curves into fragmented arabesques that swirl and spiral across the canvas.

Rather than working directly on canvas, Milhazes paints on sheets of plastic which she then lays on to her surface and peels away. From a distance, her paintings possess flawless, graphic sheen; close up, subtle shifts of tone and texture inject a vigorous, carnal vitality.

Today, her oeuvre has garnered worldwide recognition, with works residing in New York’s Guggenheim Museum and MoMA. In 2012, her painting My Lemon sold at Sotheby’s for $2.1 million, making her Brazil’s most expensive living artist at the time.

Last year the Paço Imperial cultural center hosted her first retrospective for ten years in Rio de Janeiro, her native city. For Milhazes, the experience was thrilling. “The pulse of this city is incredible right now,” she tells me at her studio in Rio. But it was nerve-racking, too. “People say, ‘I love your work’, but many have only ever seen it in books.

”This year, her sights are set on her first major U.S. retrospective, at the Pérez Art Museum Miami. Milhazes is keen to make her mark on a city she views as “a bridge between North and South America.” She is also enthused by the museum’s spectacular new building, whose glass walls are framed by a pergola of hanging gardens.

“I love the way that nature is integrated with the space,” she says, adding that the rapport with flora mirrors the tension in her own work, which thrives on the clash of landscapes. “I love to be surrounded by the city and yet also by nature. That’s why I love Rio and Miami.”

Your address: The St. Regis Bal Harbour Resort

In Italy, luxury has long been associated with food. When Catherine de Medici, great-granddaughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent, moved to France in 1633 to marry Henry II, a bevy of cooks followed in her wake, heralding the first export of Florentine cuisine that would go on to spread across the globe. Some 400 years later, many of the world’s most prized gastronomic products are still produced in Tuscany, from single-estate olive oils to sought-after wines, cheeses and treasured truffles.

Remarkably, many of these highly regarded foodstuffs are still produced by the same families who once fed Europe’s aristocracy during the Renaissance. Here, we profile three of them: two noble families, the vintners Marchesi Antinori and the olive-oil producers Marchesi Mazzei, who have been growing grapes and olives for more than 600 years; and the Brezzis, the Tuscan kings of truffles.

The Brezzi Family

Eugenio Brezzi was six years old when he found his first white truffle. Standing by his father in a pine forest collecting cones, he suddenly saw a strange dog digging something up. It was a truffle. Thrilled by the idea of a creature helping man to find such a treat, he took his father’s dog Lola into the forest the next day and found two more. And so began the world-renowned Eugenio Brezzi truffle business.

Today, the 93-year-old is as passionate about the fungi as he was as a child, explaining how the seasons bring different qualities to the truffle. “The white Alba truffle, the most valuable, ripens in autumn,” he explains. “The best ones will have been nibbled at by animals, which only go for the truffles with the strongest scent,” adds his son Valdimiro, who now runs the family business at Grosseto, near the Tuscan coast.

Like many family businesses, the company headquarters abuts the family home, and it is filled with memorabilia from the family’s other passion, travel. The walls are a patchwork of photographs recording epic trips around the world in cars, on motorbikes, horseback and on foot, and there is an enormous map criss-crossed in thick black pen showing itineraries.

It is beyond this office that the truffle rooms lie: spotless areas in which the fungi are inspected, scrubbed, stored, packaged and exported to prestigious stores throughout Italy and across the world as far as Australia and the United States. Here, three members of staff work diligently with their organic gold, some packing up whole truffles, others making white truffle purée to a recipe created by Eugenio Brezzi many years ago.

The Brezzis use no chemical aromas; all of their products are 100 percent natural. “To do things well is the best lesson in economics,” explains Valdimiro, taking a handful of perfect white truffles from a fridge: all perfectly shaped, unmarked and absolutely fresh. This little pile, he estimates, will be worth about $11,000.

Although the Brezzis are master truffle merchants and renowned throughout the world, theirs is a business for which they cannot plan. The truffle grows entirely wild, they explain, and no one can anticipate where it will grow or can plant it. Which is why the family explores forests all year round. Between December and March they will go out hunting for black truffles, also known as a Périgord truffle. Then comes the season for white spring truffles, followed by black summer truffles and finally the white Alba truffles.

A good harvest depends purely on nature’s goodwill. “The deeper in the ground the truffle is found, the better it is,” explains Valdimiro. And it is only the best specimens that will be sold. “If they’re less than perfect, we eat them ourselves.” Which is why Eugenio, Valdimiro and his son Ludovico have just enjoyed truffles with their lunch. As perks of the job go, it’s one that many of their customers would surely envy.

The Antinori Family

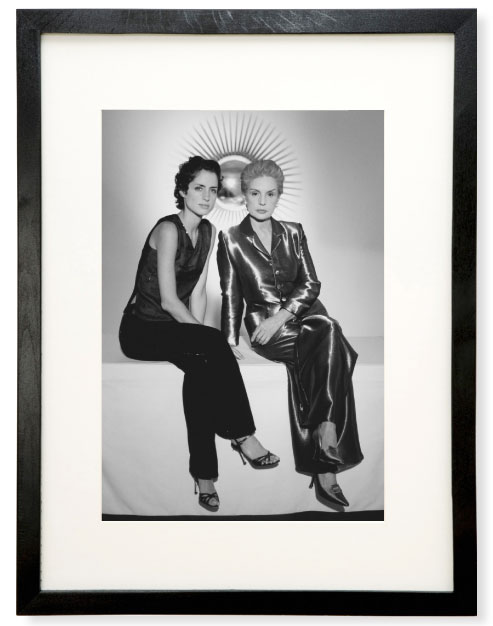

Who needs sons when you have three daughters – particularly ones as capable as the progeny of legendary winemaker Piero Antinori? Today, alongside their father, Albiera, Allegra and Alessia Antinori run Marchesi Antinori, one of Italy’s best-known wine labels.

Since their ancestor Rinuccio di Antinori started growing grapes at Castello di Combiate near Calenzano in 1180, the family business has expanded all over the world. Today, having passed through 26 generations, it employs almost 400 people worldwide and has vineyards comprising 1900 hectares in different regions of Italy and 540 hectares of vineyards abroad, from California’s Napa Valley to Chile, Romania and Malta.

While Albiera, the eldest of the daughters, spearheads worldwide marketing, Allegra oversees Antinori restaurants and Alessia, the youngest, runs a family farm near Rome, producing organic wines and cheeses sold in the family restaurant, La Cantinetta Antinori. The first restaurant opened in 1957 in Florence, and it now has offshoots in Zurich, Vienna and Moscow, with another due to open imminently in Baku, the oil-rich capital of Azerbaijan. “The idea is to export our gastronomic lifestyle around the world, centered around our wines,” explains Allegra.

Keeping the Antinoris’ rich heritage alive is constantly on the sisters’ minds – hence their decision to move from their historic headquarters in a 16th-century palace in the heart of Florence to Il Bargino, a splendid avant-garde cellar in Chianti’s rolling hills. More like the sprawling control center of a Bond villain than a wine vault, the 540,000 sq. ft. building is seamlessly integrated within the landscape and almost totally camouflaged. The only part completely visible to the naked eye is a panoramic terrace from which visitors can admire the vineyards, planted mainly with sangiovese grapes.

As Albiera shows us round their new cellars, her handsome features every bit as classic as those of a Renaissance Madonna, she explains how the company reached a turning point in the 1970s with the creation of its flagship wine, Tignanello. A blend of sangiovese with non-traditional grapes cabernet sauvignon and cabernet franc, which was then aged in small French barriques, it was hailed as a Super Tuscan in America, and was a harbinger of the success to come. “It was then we realised that the quality of the grapes was paramount,” continues Albiera. “We knew we had to work during every phase in the vineyards, as well as in the cellar, with the aim of producing the best possible wines without compromising the purity of typical Chianti terrains.”

Although the family’s vineyards are among the oldest in Tuscany, it is essential, Albiera says, for the Antinoris to continue to move forward. “We are always experimenting, because there could always be something new we could improve on. That might be in the vineyards and the cellars, seeing new clones of local and international grapes, experimenting with cultivation techniques, altitudes, fermentation and barrels. And that’s what is exciting: as a family, our work is never done.”

The Mazzei Family

Among the ten oldest family businesses in Italy is that of the Florentine Marchesi Mazzei. They have been making wine and olive oil for nearly 600 years at Castello di Fonterutoli, where they live for part of the year. Known since Roman times as Fons Rutolae, a stopover for travelers commuting between Florence and Siena, the estate came into the family in 1435. It was here that Filippo Mazzei lived during the mid-18th century before traveling to America, at the behest of Thomas Jefferson, to plant vineyards at his estate at Monticello in Virginia: the first in that part of the New World.

Today, Fonterutoli is principally run by two of the middle Mazzei brothers, Filippo and Francesco: both CEOs. Their father Lapo Mazzei is the president, while their elder brother Jacopo and niece Livia are also on the board of directors. Their mother Carla is also active, cultivating lavender on the land, producing small batches of oils and soaps that go on sale at the shop that greets visitors at the very top of the hamlet. Like the Antinori family, they have a magnificent state-of-the-art cellar designed by the CEO’s sister, Agnese Mazzei, an architect and also a member of the board.

“We employ 54 people, but this is a seasonal business so the number of our employees increases during harvest time,” says Francesco Mazzei, as he shows us around the mill where the olive oil is produced. A keen sportsman, he sometimes cycles the 20 miles to and from Florence.

The large building is surrounded by 3,500 olive trees of different varieties – frantoio, leccino, moraiolo and pendolino – from which the celebrated Castello di Fonterutoli extra virgin olive oil Chianti Classico DOP is derived. The dark oil, rich with hints of artichoke and thistle, is sealed in a squat, dark-glass bottle that bears the family’s golden crest.

There are no great secrets, the family maintains, to producing olive oil: it is a process established in ancient times that has changed little over the centuries. But there is an art to producing the very best oils. All of the Mazzei olives, for instance, are picked by hand – mostly in November – before they’ve reached maturity to retain the fruity taste typical of Fonterutoli. They are also pressed within the space of two hours in an atmosphere with a partial, or total, absence of oxygen, depending on the variety of the olives.

The family’s investment in high-tech equipment has meant that they have been able to develop the processes even further. Oil can now, for instance, be extracted even from the smallest lots of olives, so that “cru” bottles can be produced for those with more discerning palates.

The aim, Francesco explains, is to make the same products created by their ancestors, but to make them as refined as possible. “We want to keep alive historical and family values, but with new tools, to make them the very best we possibly can.”

Photographs: Magnum Photos

Your address: The St. Regis Florence

“The maps of ancient Jerusalem are all fabrication, while celestial maps are an attempt to impose the Greek myths on to the night sky,” says Jay Walker of the Walker Library of the History of the Human Imagination in Connecticut.

Today, printed maps of the ancient world have never been as prized, or as celebrated for their rarity and their beauty. The oldest date back to the early days of printing in the 15th century, when European explorers started documenting their travels, and hit an aesthetic high in the elaborately decorated works of the Dutch mapmakers of the 17th century, the so-called Dutch Golden Age.

Although prices for antique maps start at about $100, most purchases are in the low five figures. The most expensive single printed map sold to date is Abel Buell’s A New and Correct Map of the United States of North America from 1784, which fetched $2,098,500 at Christie’s, New York in 2010. Seven-figure sales such as this are becoming more and more common, with dealers pinning great hopes on increasing interest from the Far East and Southeast Asia. “I’m off to Hong Kong for the second time in two months,” says Daniel Crouch, of the eponymous map-dealing firm in London. “Five years ago I would buy in China and sell in the U.S. Now it’s the reverse.”

What are these new buyers going after? So-called “curiosity maps”, in which land takes the form of figures – monarchy or politicians, for example – are well-liked. Among the most sought-after are Ptolemaic maps, based on the shape of the world set out by Claudius Ptolemy around AD 150; the last one sold to an individual by Sotheby’s in 2006 was printed in 1477 and fetched £2.1 million (about $3.4 million). The most undervalued, Crouch believes, are whole atlases. “You can get a globally significant world atlas collection for the same price as a mediocre Impressionist painting,” he says.

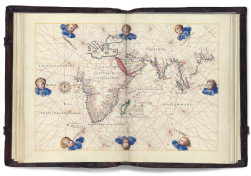

Christie’s, meanwhile, has seen prices soaring for masterpieces which are rare, in fine condition and have an excellent provenance. Just two years ago at the Kenneth Nebenzahl sale in New York, the auction house sold a 1542 portolan atlas by Battista Agnese for $2,770,500 – well above the original estimate of $800,000 to $1,200,000.

The internet has also had a huge part to play in rising prices, creating “a transparent marketplace where map and globe values can be easily traced,” according to Julian Wilson, specialist in books and manuscripts at Christie’s. “It’s also facilitated the globalization of the market, which was dominated by Western buyers ten years ago,” he adds.

Massimo De Martini of the Altea Gallery in London points out, however, that many people still like to make their purchase in person. “The internet is like our shop window,” he says. “Part of the fun of collecting is the hunt. But people still try to feel the quality for themselves.”

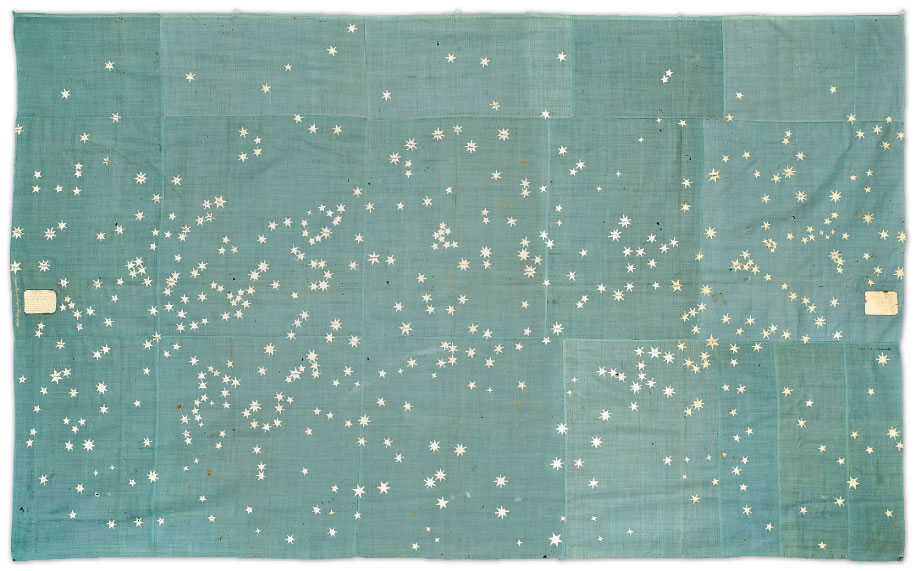

Experts advise new buyers to start small, looking for anything with original hand-painted colour on it, and to collect what they love. For Daniel Crouch, this is maps that are unusual. “My favourite item is an original 1930 copy of a 16th-century book called Astronomicum Caesareum by Petrus Apianus,” he says. “It’s made with moving parts and is full of dragons.” Wilson advises looking to the skies. “Celestial maps such as Star Spread by E. Hattie Rogers (1863) will pick up soon,” he says.

Perhaps surprisingly, new territories are still being charted. “NASA has produced a complete set of geological maps of the moon,” says Wilson. “One day, they, too, will be seen as a part of history.”

Where to buy antique maps

Altea Gallery, London, alteagallery.com; Antipodean Books, Maps and Prints, New York, antipodean.com; Christie’s, New York, christies.com; Geographicus Rare Antique Maps, New York, geographicus.com; Sotheby’s, New York, sothebys.com; Daniel Crouch Rare Books, London, crouchrarebooks.com

Where to see antique maps and globes

The Map & Atlas Museum of La Jolla, San Diego, mamlj.org; The National Maritime Museum, London, nmm.ac.uk; The British Library, London, bl.uk; The Newberry Library,

Chicago, newberry.org

Your address: The St. Regis New York

Images courtesy of Christie's and Sotheby's

How did you come to be editor of Vogue China?

Before I came to Vogue I was thinking seriously about quitting fashion journalism. I had been editor-in-chief at Marie Claire Hong Kong and Elle China, but although I studied law at university, I’d never practised it. I wanted to do something other than fashion journalism, because I thought I’d done it all. Then Condé Nast came calling. I mean, it’s Vogue. How could I say no?

Vogue China has a print and online readership of more than 1 million. Are you surprised by how successful it’s been?

Yes and no. China was tipped to be the next emerging market in fashion when we launched in 2005, and our launch issue sold out immediately, which was an encouraging sign! At the time, I said that if people are riding a horse, and you ask them what they need, they would say a very fast horse, until you show them the car. I think the time was right to show them the car.

Has the way Chinese women approach fashion changed since 2005?

Definitely. Their approach has matured at such a rapid rate. Obviously there are people who love the big brands and logos. But within the first- and second-tier cities, there is an incredibly sophisticated consumer base. These women travel extensively, they go to the shows in Paris, they buy couture. Women here like to look polished. They like beautiful handbags, lovely high heels, dresses and having their hair perfectly done. People don’t admire “casual chic” here so much. Having said that, vintage is really taking off lately. In Beijing and Shanghai, there are some very niche spenders: money is not an object, but they want to buy the right things. Some of them might buy only runway collections, for instance. Others are moving away from logo products; they feel that the newcomers from second- and third-tier cities are wearing those, so they want to show they have moved on.

Are Vogue editors friends or rivals?

There is a certain identity that is shared by being an editor-in-chief of Vogue, because it is the pinnacle of a career in fashion magazines. However, we work within very different markets, with very different readers, so at the end of the day we are very independent of each other.

The speed of change in China looks incredibly fast. Does it feel that way?

Yes. Even the architectural landscape around you changes at a rapid speed; buildings seem to come and go. However, when you live here for so long, you get used to change. People are accustomed to a very fast pace of life. Sometimes, when I go to Europe or to America, I’m like, “Oh, this is still the same as it was two years ago.”

Do you have a good work/life balance?

I used to work all the time, then a few years ago I had my daughter, Hayley. I really felt the impact of these choices that you make between work and family. It’s so important to give it your all in both aspects, and it’s something that I really try to do. Even though I travel so much, I often end up taking day trips to different continents so I don’t miss out on too much.

What are the best and worst things about living in Beijing?

Beijing is a difficult city to live in, with its infamous traffic and pollution, but it is the center of China, and that has its appeal. Parts of the old city, around the Imperial Palace, are very beautiful. It doesn’t have the cosmopolitan charm of Shanghai, but at the end of the day, the majority of the movers and shakers are here, so Vogue is, too.

How different is your daughter’s world to the one you grew up in?

I can’t even begin to tell you. My daughter has been travelling with me since she was a baby – she’s such a little jetsetter. We grew up with nothing by comparison: there was no fashion to speak of, no diverse cuisines or restaurants, nobody traveled anywhere. Now, new shopping malls are opening up everywhere, people are exposed to so much via the internet, and everybody is on their phones all the time. Hayley knows her way around an iPad, and she’s only six. That would have been unimaginable when I was growing up. I still have a picture of when I was a kid, holding Mao’s Little Red Book. My grandma was a tailor, and she made me some really tight black-and-white check trousers to wear to school. Everyone else was in a blue uniform. I loved my trousers, but when I went to school they whispered, “Bourgeoisie.” That was a very bad label. After that, I didn’t dare wear them ever again.

Would you ever consider giving up work to be a full-time mother?

I don’t think so. Much as I love my daughter, I would miss my hectic life. One benefit we have from Chairman Mao is his slogan, “Women hold up half the sky.” That era basically

lifted women to the same status as men. As a result, women of my generation feel that we have to work. It never occurred to us to stay at home. If I told my mom I wanted to stay at home, she would think my life a total failure. Maybe it’s nice sometimes to go to the spa and have your nails done, but I don’t think that’s me, and I don’t think it’s the majority of Chinese women.

Is there any job you would like to do after Vogue China?

I never thought I would be in this job this long: nine years now. Friends still tease me about it, because when I joined Condé Nast, I said I would probably stay for two years

and move on to something else once Vogue was successfully launched. But we just kept having new ideas. I always believe there is life after Vogue. Life is short. If one day I stop feeling inspired, I will move on to something else. But I don’t think I will go back to law now.

Where in America have you traveled? What do you like about the country?

I travel to America quite a lot, but I always go on business trips with packed schedules. I love New York – I like the energy, and I love how everybody there is very direct. They know what they want, and they’re not afraid to go after it.

How would you describe your personal style?

In this industry you’re forced to make choices about fashion every single day, and with a young child, and the school run in the morning, I really try to keep things simple. I love one-piece dresses, and Jason Wu always makes ones that are chic but comfortable for running around in all day. Accessories are great for making an outfit stand out, and Lanvin does such fun pieces. I have a particular weakness for coats, and I find the shapes from Marni work really well for me.

What was the inspiration behind your trademark asymmetric haircut?

It was really the notion of my hairdresser at the time. He said he had an idea for a cut and couldn’t think of anybody who could carry it off, apart from me. I said, “Go for it,” and it’s been this way ever since.

Are we going to hear more from Chinese fashion designers in the future?

We’ve always been very conscious about promoting Chinese designers since our first issue, but I must admit that, back then, it was a bit of a struggle to find anybody. Now, we have people like Masha Ma and Uma Wang who show at Paris and Milan. Huishan Zhang, who we’ve supported from the beginning, has a presentation during London Fashion Week and has just won the Dorchester Collection Fashion Prize. They’ve come so far over the past few years, and I think they’ll go even further.

Your address: The St. Regis Beijing

The recycled fashion shop in Rome by Livia Firth

RE(f)USE , 40 Via della Fontanella di Borghese, carminacampus.com

I always enjoy wandering along the magical street of Via della Fontanella di Borghese, in the historical heart of Rome. Not just for its history and culture. I go primarily to see Ilaria Venturini Fendi’s magical shop, RE(f)USE. Ilaria launched her ethical fashion brand Carmina Campus a few years ago because she wanted to make her business more sustainable and to find a way of extending the life of objects.

It is the only store I know of whose fashion and design objects are all made exclusively with recycled materials. They use all sorts of things – remnants from factories, discarded fabric, end-of-line stock, vintage snippets – which are then all assembled and reused to create something with a totally new shape and function. When you enter RE(f)USE, you feel like Alice in Wonderland: the selections of jewelry, accessories, tables, chairs, sofas, lamps, chandeliers and other pieces of design are all unique. There are all sorts of incredible works by some of the most unconventional designers from all over the world, including the Berlin-based Stuart Haygarth and the Belgian Charles Kaisin.

The first floor is the place that reflects Ilaria’s real passion. It’s all paneled with mirrors and stocked with dozens of handbags, each of them different styles, sizes and colours and upcycled by artisans from Italy and Africa. What makes them extra-special is that each piece carries a tag, telling its story, listing the materials that have been used to make it and the number of hours spent to produce it by hand. To me, this place is temple of design. It’s somewhere I love going into and never regret buying anything from.

Your address: The St. Regis Rome

The California chocolatier by Sally Perrin

Christopher Michael Chocolatier, 2346 Newport Blvd, Costa Mesa, chrischocolates.com

This is really a hidden gem, because it’s in an unassuming shopping center on the Newport Peninsula where you’d never expect to find something quite as incredible. It is total chocolate heaven. To the right, as you walk in, there’s a counter featuring all the truffles, ganaches and confections of the day, and to the left, ready-made packages which make easy-to-grab gifts, including the store’s famous chocolate bars with unique flavors.

The chef-owner, Christopher Michael Wood, discovered a chocolatier in SoHo in New York, and in 2006 decided to try to bring the same level of craft and detail to his native California. Every time I go to the Dana Point area, I have to go and get something: a bar, truffles, bonbons, chocolate-covered nuts... current favorites are his balsamic-caramel and chocolate-covered strawberries, his unusual bars, like the spicy pomegranate and lime and his lavender-infused caramels. My husband absolutely loves the Sizzling Bacon Bar, which is Venezuelan chocolate flavored with sea salt, smoked bacon and popping candy.

What’s great is that they take classics and twist them; they take a risk, which is what I like to do. I like the unusual, the untried, the unexpected. And I like the fact that it’s small and artisanal. Christopher takes care of every little detail, whether that’s the painstaking airbrushing of designs on his chocolates or the unique flavors he creates on the premises. I am not sure whether to thank the friend who brought a box to a dinner party we had at our home a few years ago. I had three pieces and have been hooked ever since!

The homewares store in Mexico City by Kiyan Foroughi

Common People, Emilio Castelar 149, Colonia Polanco, commonpeople.com.mx

This store, in a beautiful four-story 1940s colonial mansion, is on an upmarket street in the characterful area of Polanco, which is known for its architecture, restaurants and hotels. From the outside there is no hint of what is within and even when you step through the door, it seems more like a gallery than a store. Nothing’s straightforward-looking. All the merchandise looks as though it’s been caught on a strong breeze: there are bags, plates, cushions of all sorts, piled high and hanging from walls and roofs.

The idea of the owners, Monika Biringer and Max Feldman, was to create “a place filled with uncommon things for common people.” And that’s what it is. There’s something to contemplate wherever you look and nothing is the same. There are all sorts of names, from independent local artists to international figures. So you’ll get local companies such as TOSCA, which produces big, chunky jewelry, alongside Commes des Garçons and Vivienne Westwood, clothing piled alongside homewares, and high-tech gadgets next to projects by artists and musicians. It’s a bit like Colette in Paris. One minute you’ll be looking at books from Assouline, the next furniture from Vitra and then vintage pieces from the forager Emmanuel Picault.

The owners are involved in the creative scene in the area – fashion, design, art, music, everything – and incorporate that into the store wherever possible, which gives it a lovely creative edge. What’s great, too, is that although the assistants are incredibly cool, they’re not at all snobby and will know all about the makers: who they are, where they’re from and how they’ve made things. So every time you go in, you learn. A friend who recommended it to me suggested that I didn’t go in if I was in a hurry, and he was right. If you’re not shopping, then there’s a café and a beautiful ornate staircase to go up, to discover a whole other floor, then another, then another…

Your address: The St. Regis Mexico City

The haberdasher in New York by Collette Dinnigan

Tinsel Trading Company, 828 Lexington Avenue, tinseltrading.com

This shop is so tiny that it would be easy to miss. Its previous address, on West 38th Street in the Garment District, was even smaller. But wherever its location, it has always been packed from ceiling to floor with treasures. Four generations of the same family have worked in the business since the current owner’s grandfather, Arch J. Bergoffen, took it on in 1933, specialising in French tinsel and metal threads, and it has much of the same charm, if not as much clutter or dust, as the original.

It’s the ultimate shop for treasure seekers: full of shiny, beautiful ornamentation that has been collected by its owners for decades, from all over the world. There are antique trims and beading from the 1930s and 1940s, metal fringing, tassels, vintage cards from 1900, old labels, waxed flowers. The things I most love are the buttons. In the old shop, you had to go through hundreds of boxes and jars to find the ones that were really special: those that were hand-painted, glass, covered in silk and velvet, collected from old military jackets. Sometimes they might only have enough for ten dresses; other times for whole collections.

Now the shop is much more organized. The buttons are all in boxes with a button sewn on to the front, so you know what’s inside. The rolls of fabric are also now merchandised according to colour, with a flower at the end of each roll, so the whole wall looks like a spring field.

What’s great fun is that you never know what you might find. Once I came out with a collection of big letters from the 1930s covered with real, old-fashioned glass glitter. Another time I found beautiful old tags and some quaint pieces of original embroidery and lace.

Today, it has been brought much more up-to-date; they now even have a website, which is handy if you can’t get there in person. Also, if you let them know what you want, they can often help you find it from one of their many contacts all over the world. It’s one of those quirky, quite peculiar places that is a real one-off. Just talking about it makes me long to go and rummage around in it.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

The sushi bar in Osaka by Maria McElroy

Yamane, 1-3-1 Doujima Kitaku (+81 6 6348 1460)

The exclusive Kitashinchi neighborhood is the beating heart of Osaka at night, and this sushi restaurant is right in the center of it. Above the narrow streets are a tangle of neon signs and boards inviting people inside, to secret little places where geishas once delighted customers. Because the area has such a lovely feeling, it’s where the cream of Osaka society goes. There are half a dozen Michelin-starred restaurants around, but for me and my Kyoto-born husband, Yamane is by far the best.

You’d never know from the outside that it was so special. It’s in an unassuming building and behind the sliding door is an intimate space, with a delicate blond-wood latticed sushi bar, behind which the master sushi chef Mr Yamane and his staff work.

There is nothing quite like sitting there, watching the action. Like most old traditional establishments, the fish from that morning’s catch at Sakai fish market is not on display, but kept in boxes of ice and taken out when the chefs need to slice it with their precision knives. Some of them have been sushi chefs for decades and are masters in local specialities: mehari, a heady combination of rice with fatty tuna and salmon caviar wrapped in pickled mustard or square hakozushi, topped with marinated mackerel and kelp. Although I always have their tuna, octopus and flounder sushi, I love their dashimaki tamago, a thick, warm rolled omelet, much softer and more pliable than those you find in Tokyo.

The food, as you’d expect from someone with such a precise eye, is presented in an extremely elegant way, on ceramic plates made by the famous ceramicist Ippento Nakagawa. And the smells that waft through the air, of warm soy sauce, incense and the freshness of the sea, are as enjoyable as the sounds of the chefs chatting and laughing. The people in this area of Japan are known to be very funny and full of life, and although everyone is hugely respectful of Mr Yamane, his restaurant is full of warmth and humor.

Your address: The St. Regis Osaka

The stationery shop in Washington, D.C. by Fareed Zakaria

Thornwillow, The St. Regis D.C., 923 16th Street, thornwillow.com

Entering Thornwillow is like entering a library or a gentleman’s club. It even has a “librarian” to look after you, who encourages you to have a cup of tea or a whiskey while you sit and browse books. It’s an extraordinary publishing house: a place where you can buy books, or get them printed, and walk out with incredibly beautiful stationery. My wife and I had our New Year cards printed there and as usual, the owner, Luke Ives Pontifell, came up with a wonderfully whimsical design: a flying pig!

He is one of those people who is extraordinarily wise although still pretty young. He wears wire-rimmed glasses and three-piece suits with a pocket square so you feel a bit like you’re talking to someone from another era.

We’ve also visited the place in which the books are made, an old coat factory in Newburgh, New York. There, we realized what a craft bookmaking is: they have lots of men, I think from Eastern Europe, who obviously make each book as a labor of love. They are expensive, but each one is fashioned by hand, their handmade paper covered in beautiful leather and each special for a different reason, whether it’s President Obama’s inaugural speech or a famous old novel they have reprinted.

I am lucky enough to have a set of simple notecards and matching envelopes printed with nothing but my name and a charming little vellum-based desk calendar that sits on a little gold easel. It’s a lovely old design and, in a world in which almost everything is on our phones, it is nice to have something on your desk that reminds you quickly about the passing of time. You don’t have to fiddle around to find the calendar app.

Thornwillow offers a reminder of the efficiency of paper and the beauty of the printed word. Whenever I visit, I am hit by not just the intellectual power of the printed word but the emotional power of seeing something beautiful written on paper. It always makes me feel great.

Your address: The St. Regis Washington, D.C.

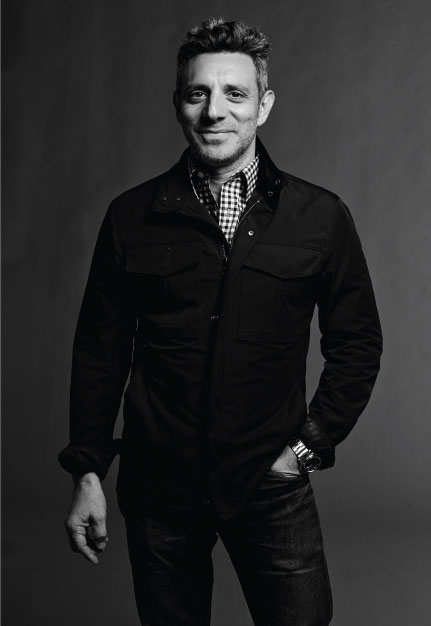

A born-and-bred New Yorker, John DeLucie was a late starter in the culinary world, discovering his calling at the age of 29. Since then, he has become a major figure on New York’s restaurant scene, making his name as the executive chef and partner of the Waverly Inn, the Greenwich Village restaurant that became the ultimate hangout for the city’s glitterati. DeLucie is now proprietor and executive chef of the Lion, Bill’s Food & Drink and Crown, three of Manhattan’s most celebrated restaurants. His latest project has been to reimagine the culinary offering at the refurbished King Cole Bar & Salon at The St. Regis New York.

What’s your earliest food memory?

When I was a child we lived with my grandparents, who were Italian immigrants, and one of my earliest memories is of being in the kitchen with my grandmother. My grandfather sold fruit and vegetables, and he would bring home any produce that didn’t sell that day. It was grandma’s job to make dinner with it. So it could be things like dandelion greens or broccoli rabe – food that was pretty unusual in America at that time. I remember having dinner at a friend’s house in my teens and eating iceberg lettuce. I didn’t even know what that was.

What was the first thing you ever cooked?

Ditalini with tomato and celery leaves and chickpeas – basically pasta fagioli. I’d seen my mother make it a thousand times and one day when I was about 13 I thought, “I want to do that.” I remember painstakingly taking the delicate light-colored leaves from inside the celery, not the big overgrown darker leaves – just like I’d seen my mother do.

Who taught you to cook?

My mother, my aunts and grandmothers were all instrumental. My dad had 11 siblings and my mom had four brothers and sisters, so every Sunday we would gather somewhere with a lot of people. There was always tomato sauce and pasta or ravioli and some kind of meat. It was a very food-oriented family.

What’s your favourite Italian-American dish?

Veal milanese. I just love a pounded veal cutlet drenched in egg and breadcrumbs and pan-fried. It’s the most delicious thing in the world.

What made you become a chef?

I had a lot of different jobs after college. I was a musician. I sold advertising, I represented fashion photographers, I worked as a headhunter in the insurance-brokerage industry. Around the time I was 29 I realized I wanted to cook for a living, so I enrolled on a masterchef class at the New School, and it turned out I had some aptitude. When the course finished I got a job making salads in a very busy restaurant on Third Avenue.

Did you ever have any cooking disasters?

One of my first jobs was at Dean & DeLuca. They asked me to make a potato salad and I got so excited that I forgot one vital ingredient – the potatoes.

How would you describe the menu you’ve created at the King Cole Bar & Salon at The St. Regis New York?

Over the years there have been some amazing chefs at The St. Regis New York, like Gray Kunz, Christian Delouvrier and Alain Ducasse. So when it came to creating the menu, we felt it had to be a real departure from the past. We took a simple approach: super-accessible dishes such as trout wrapped in prosciutto and grilled merguez. We were thinking about the modern traveler who would relish the splendor of the place but not want to get bogged down by food that was too traditional or too complex.

Where’s the best city in the world for food at the moment?

There are so many hotspots – Spain, Italy, the Nordic countries – but Brooklyn is really interesting right now. It’s a very exciting time. Trend-wise, vegetables are pretty hot – dishes such as carrots wellington and parsnip steaks. I think it’s great that we’re paying more attention to stuff that’s growing.

What’s your ultimate comfort food?

A great pizza with a delicious chewy crust – there’s nothing better. I like it best with just tomatoes and chilli and oregano.

What’s the most memorable thing you’ve ever eaten?

I stumbled upon a bakery in Naples with an old pizza oven that had been there for centuries. They were making flatbread, so we bought some, along with some buffalo mozzarella and a bottle of wine, and we sat in the park. It was just glorious – an incredible sensory experience.

If you could fly off right now and eat at any restaurant in the world,

where would it be?

Shiro’s Sushi Restaurant in Tokyo. Simple, fresh, honest – that’s the kind of

food I like.

Your address: The St. Regis New York

The grand British art historian Kenneth Clark, once the director of the National Gallery in London, owned a lot of art. But among Lord Clark’s favorite works was a piece made by Duncan Grant – a precious and much-loved artwork that he stepped on almost every day. Sacrilege? Not at all, because the artwork in question was a rug: designed especially for his eminence by the Bloomsbury Group artist, and frankly, far from the average humble floor covering.

Which goes to show that a rug can be a work of art and usable. There’s certainly a lot to love about a great rug. Like “slow food”, rugs are perhaps the ultimate “slow” art form. They take months and even years to complete, are usually made of natural fibers, last for centuries if kept properly and can be rolled up and transported. They are also warm and tactile.

Which is probably why the artist-designed rug is having a renewed moment in the art and fashion worlds. Pioneering the revival is the Rug Company, which has showrooms across Europe and North America, as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong and the Middle East. It has placed itself firmly in the vanguard of artist and designer-made rugs by commissioning and selling rugs created by such fashion figureheads as Alexander McQueen, Vivienne Westwood and Diane von Furstenberg, as well as a series of one-off tapestries from contemporary artists including Kara Walker, Fred Tomaselli (whom we feature on p.74) and Sir Peter Blake.

“Artists and designers’ contemporary rugs have become really collectable in recent years,” says Christopher Sharp, CEO and co-founder of the Rug Company together with his wife Suzanne. “The nature of their production – they’re knotted and woven entirely by hand by a small group of skilled craftspeople – means that their production is limited, and that demand outstrips what we’re able to produce.” So they’re also an investment, one reason why artists’ rugs are flying off the floors of the Rug Company’s stores, everywhere from San Francisco to Mexico City.

The swell of interest is not limited to New York. Earlier this year the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris hosted Decorum, an exhibition featuring more than 100 rugs and tapestries created by artists ranging from Francis Bacon and Pablo Picasso to Le Corbusier and Louise Bourgeois. This summer in London there’s been an exhibition called Form through Colour, both showing and selling rugs produced by Bauhaus designers Josef and Anni Albers, as well as contemporary British artist Gary Hume.

The organizer of that exhibition, textile and rug-designer Christopher Farr, whose eponymous company has offices in London and Los Angeles, was a frontrunner in the current rug boom. “When we started making artist-designed rugs [in the early 1990s] people laughed at us,” says Matthew Bourne, Farr’s business partner. “Nobody else did it at the time. But we’ve always asked, ‘Why can a sculpture be a work of art and not a rug?’ ” Christopher Farr now sells rugs by a roster of big-name artists and designers that includes Andrée Putman, Jorge Pardo and Sarah Morris.

As Bourne notes, artistic rugs have seen previous high-water marks: “In the 1920s the groundbreaking Myrbor gallery in Paris, led by Marie Cuttoli, sold rugs by Picasso and other artists.” Then, into the 1950s and 1960s, rugs came on to the market bearing designs by artists including Ellsworth Kelly and Alexander Calder. But it took until the 1990s to feel the real heat of revival, which Bourne attributes to “a search for new and durable art forms that are useful as well as beautiful”.

Cast around, and you’ll find plenty more manifestations of the new art rug. Notable in the genre are Michelle Evans’s wool and silk rugs, which have just been exhibited at the J+A Gallery in Dubai; ChiChi Cavalcanti’s graphic, Brazil-influenced rugs, which are prized by architects and interior designers; and Tania Johnson’s meditative rugs based on photographs of natural phenomena such as water. “They take months of painstaking work,” says Johnson, whose clients have included Calvin Klein Home.

There’s even an avant-garde strand in artistic rug-making. In May, at Barneys in New York, an exhibition called Volume #1 showed the results of a limited-edition art-rug project from luxury rug-makers Henzel Studio, which included a Juergen Teller portrait of a nude Vivienne Westwood in rug form, a rug by Helmut Lang, and an astonishing floor-piece by Marilyn Minter called Cracked Glass.

Several of these rugs broke out of the classic rectangular format, and used differing weave heights to create complex images. “This collection was a way to show the rug in a broader context,” says Joakim Andreasson, curator of the project. “The idea was to bring the art rug to a new audience that doesn’t make such a distinction between applied and fine art.” It’s also worth noting that compared to much contemporary art, the rugs were relatively affordable: with prices ranging from $16,000 to $20,000, they are cheap enough, almost, to induce a serious rug habit.

We still have some way to go, however, before precious rugs and tapestries are as appreciated as they were in their heydey, during the Middle Ages. “Tapestry was then judged as a higher art than painting and was more expensive,” says Matthew Bourne. So prestigious was it, adds Christopher Sharp, that “aristocrats would roll up their tapestries and take them to other people’s castles to show them off. Henry VIII had a lot of his wealth wrapped up in them.”

It was probably industrialization that led to rugs, wall-hangings and tapestries being downgraded. “In the 20th century, makers’ skills started to disappear in the West,” says David Weir, director of Edinburgh weavers Dovecot, which itself was revived ten years ago after a period in the doldrums. “Previously we’ve commissioned artists such as David Hockney, Graham Sutherland and Frank Stella, and we’re now returning to the artist-designed rug idea – we’ve recently brought out a series of hand-tufted rugs in collaboration with artist Than Hussein Clark. Weaving translates well to contemporary art.”

Rug-making remains a slow and labor-intensive endeavor, but producers have found plenty of artisans happy to take on the challenge of making art rugs in the developing world. Christopher Sharp uses weavers in Nepal, for example, while Christopher Farr employs Indian craftsmen, and is even making rugs in Afghanistan as part of the US-led AfghanMade initiative.

The one question Matthew Bourne is always asked by buyers is whether they should, like the aforementioned Lord Clark, actually walk on their beautifully designed rugs.

“Well, rugs are made for use, and assuming they’re made well, they are very robust,” he says. “But if people want to put them on the wall, that’s also fine.” It probably depends, as much as anything, from which perspective you like to encounter your art: head on, or from on high.

WHERE TO FIND FINE-ART RUGS

The Rug Company, therugcompany.com; Christopher Farr, christopherfarr.com; Michelle Evans, aykadesign.com; Tania Johnson, taniajohnsondesign.com; Henzel Studio, byhenzel.com; Dovecot Studios, dovecotstudios.com; AfghanMade, afghanmade.com; Top Floor, topfloorrugs.com

Your address: The St. Regis San Francisco; The St. Regis Mexico City

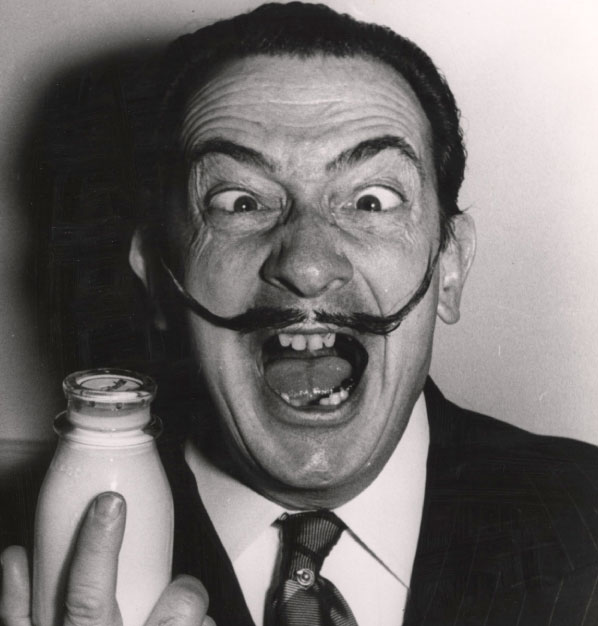

DALÍ… IS… HERE!” For 40 years this gutteral cry announced that the greatest artist of the 20th century, certainly in his own estimation, had arrived in New York at his own private fiefdom, the fabled St. Regis. And whether it was in the hushed acreage of the restaurant, the lofty grandeur of the lobby, the dark enclave of the King Cole Bar or his gilded suite with adjoining studio, Salvador Dalí adored turning this hotel into the stage of his celebrity, his one-man theatre, his private palace and zoo.

Every winter from 1934 Dalí would appear like clockwork, or rather like some distorted cog from his own surreal timepiece, to occupy Room 1610, accompanied not only by his wife and muse Gala, but also a bizarre retinue of associates and animals, including his pet ocelot named Babou. Here he would happily swish around in his golden cape of dead bees or “accidentally” let loose a large box of flies. With arms stretched wide, cane held high, moustaches pointing to the heavens, nobody knew better how to make the grandest entrance. Soon not just fans but also tourists would congregate around the hotel hoping for a sighting of him on the steps of East 55th Street, growling his war cry, each loud sung syllable: “Da-lí… is… he-re!”

No city was better suited than New York to Dalí’s unique brand of showmanship and entrepreneurial hustle, “brand” being the mot juste for this groundbreaking artist who managed to turn himself into a business model and a limited-edition luxury product endorsed by the rich and famous. And no venue suited Dalí better than The St. Regis. (In fact few hotels are as closely associated with one particular artist as The St. Regis and Salvador Dalí.) For New York has as voracious an appetite for culture as for celebrity and commerce, and Dalí was the first to conquer the city by combining all these into one irresistible package: high art and high finance, and every sort of hijinks in between. Dalí’s true celebrity, his serious worldwide fame, was entirely due to the Manhattan media machine. There was an almost symbiotic relationship between the artist and the city’s press, feeding off each other in a mutual frenzy of outrage, a tornado of publicity stoked by Dalí’s pranks and posturings, as if neither could ever get enough of the other.

None of this was an accident, Dalí having plotted it all from the first time he stepped off a boat in New York. He understood that to be a truly modern artist in this one truly modern city he had to become a mainstream star. Which is why, when he arrived in Manhattan before World War II on the steamship Champlain, at the end of an expensive marine expedition from Le Havre subsidised by Picasso, nothing was left to chance. He had even prepared his own publication for the occasion, a broadsheet with the splendid title New York Salutes Me!, which was distributed on the ship and then to the awaiting newsmen when he stepped down the gangplank into New York for the first time ever, on November 14, 1934. Dalí had well and truly arrived.

The mutual attraction between the artist and the media when he stepped off the ship was immediate. In fact, when asked to single out his favorite work of those he had brought on the ship with him, he had one already prepared. Theatrically ripping away the wrappings, he revealed his chosen masterpiece: a portrait of his wife Gala with lamb chops on her shoulders, which made not just the next day’s papers, but that evening’s edition. By the end of his very first day, Dalí was already a hot gossip item.

And so the adulation continued. His debut exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery proved an instant success, and he gave a hugely successful talk at MoMA. Soon, he was being photographed wherever he went. His famous “Bal Onirique” costume ball in honor of his return to Europe, organized by the bohemian Bostonite Caresse Crosby, was so outrageous that the next day there was a maelstrom of publicity, with photographs of his head bandaged in hospital gauze as he danced under a giant cow’s carcass.

Not that the artist stayed away too long. He soon set a pattern of travel, returning every winter, starting in December 1936 with another Julien Levy show that coincided neatly with the MoMA show Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. This was accompanied by the ultimate accolade: a portrait by Man Ray on the cover of Time magazine, which dominated the newsstands and ensured that Dalí would have to sign autographs in the street for as long as he stayed in the city. As Time put it, “Surrealism would never have attracted its present attention in the US were it not for a handsome 32-year-old Catalan.”

Just as successful as his art-pieces were Dalí’s windows for Bonwit Teller department store, where crowds jostled six-deep on 5th Avenue to admire his surrealist woman with a head of roses complete with red lobster telephone. It was in these windows, in 1939, that Dalí staged possibly his most famous New York stunt, climbing into a bathtub in a window and then crashing through the plate glass – with the bath – to thunderous applause.

For Dalí, the best thing about this event was actually to be arrested and to spend time in a real New York prison with real American criminals, before being given a suspended sentence for disorderly conduct. As he admitted, it was “the most magical and effective action” of his entire life.

In spite of this, the artist was soon asked to create one of his most important commissions: his own pavilion at the World’s Fair of 1939, which he called Dream of Venus. In typical style, he came up with an outrageous plan, featuring semi-naked swimmers, and when sponsors objected, he wrote one of the best works of his life, Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness, copies of which were showered over the city by aeroplanes as a full-scale public protest.

There was nothing more he loved than being noticed. As Nicolas Descharnes, the world’s leading Dalí expert, and son of his official personal secretary, Robert Descharnes, explains, “I remember my father recalling a walk with Dalí near The St. Regis Hotel in the 1970s, during which he was dressed in a black coat of panther skin, trying in vain to attract the attention of passersby while gesticulating with his stick. ‘Descharnes, have you seen?’ the artist apparently said. ‘It’s incredible how one can pass unnoticed in this city!’ ”

New York represented absolute energy for Dalí in his annual circuit between Paris, New York and his home in Port Lligat on Spain’s Costa Brava. It’s the city where he dynamized his career, whether during his long residence in America from 1940 to 1948 – when his and Léonide Massine’s ballet Labyrinth was shown at the Metropolitan Opera House, and he had a full retrospective at MoMA – or the winters near the end of his life.

Most of his meetings were in his “résidence d’hiver en St. Regis”, where he’d often hold court looking down on visitors from his 7ft chair, installed on the backs of four turtles. It was here that some of his most important engagements took place, whether that was receiving Helena Rubinstein’s commission to create her frescoes, or meeting for the first time the collectors Eleanor and Reynolds Morse, who went on to create the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. It was in this suite, in 1965, that he first met the young Andy Warhol, that ultimate New York artist. On a subsequent encounter he dressed Warhol up in an Incan headdress before tying him to a spinning wheel and pouring paint all over him.

It was also in 1965 that a remarkable film, Dalí in New York, was made, capturing all the magic and madness of the maestro in residence. Directed by a young Englishman, Jack Bond, the documentary captures Dalí and his circus preparing for his largest exhibition yet, at the Huntington Hartford Gallery. Bond himself stayed in a suite at The St. Regis and in the film we see much of the hotel of the era and Dalí’s “special relationships” with its residents and staff, including the famous waiter Stanley. We also see just how difficult Dalí could be. During one scene, he is filmed demanding 5,000 large black ants (having previously insisted on a sequence of exploding swans, much as at the World’s Fair he had initially conceived a set of exploding giraffes).

As Bond explains, “Dalí always knew exactly what he wanted and he got it. The doormen had to pay Dalí’s taxi fare. He was ‘grand’ in the real meaning of the word. He fitted New York like a glove, it was made for him, and The St. Regis was, and still is, the best hotel in the whole city. He was even able to paint there – he kept a special room as his studio.”

Bond’s film about New York is on permanent show at the Dalí Museum in Florida, a fitting homage to the importance of that one city, and one hotel, in the artist’s life, the place where he turned even his social world into one fantastic happening. As Hank Hine, director of the museum, puts it, “One of our greatest Dalí works is from 1976 and is entitled Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea Which at Twenty Meters Becomes the Portrait of Abraham Lincoln (Homage to Rothko). This masterpiece was painted in the studio that Dalí kept at The St. Regis. The hotel is a living reminder of the vitality of the life of the city and the special vibrancy of great hotels.”

The Dalí Museum is at 1 Dalí Boulevard, St Petersburg, Florida; dali.org

Your address: The St. Regis New York; The St. Regis Bal Harbour Resort

Images by Getty Images, Bradley Smith/Corbis, Bettmann/Corbis, WireImage, David McCabe

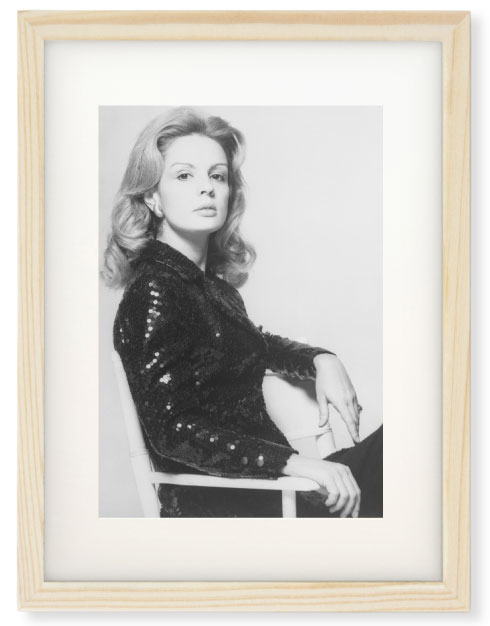

You waited until 1981, when you were 42, before launching your fashion house. Why?

There comes a time in your life when you need to do something new, and that was the right time for me. I’d never done anything before. I asked my friend Diana Vreeland what she thought about me designing some materials and she said, “That’s so boring. Why don’t you design a fashion collection?” She gave me the idea.

What did your husband think of you starting work?

He believed that I should do it, and that was very important for me. You have to have the support of your family, because if you do something they don’t agree with then it’s hell.

Did you ever feel any self-doubt?

Sometimes everything’s fantastic and you think you’re on top of the world; other times it’s more difficult. Fashion, and dealing with the egos in the industry, is a very difficult business.

Were you ambitious?

You have to be ambitious in fashion, otherwise you won’t get anywhere. You have to persevere and realize that you are designing for many different tastes, not just your own. I design things that I wouldn’t wear, but I know they’re going to sell.

You had no formal design training. Did that matter?

No, because in design, the most important thing is to have an eye: for proportion, for mixing colors. You can go to fashion school and learn how to cut a pattern and how to sew, but if you don’t have the vision you won’t know how to put it together. I sketch very badly, but I know exactly what I want. I can’t sew on a button, but I know how it should be sewn on.

Why did you choose to live in New York?

I’ve been in love with New York since I was a child. It’s a very glamorous city, and one of the few cities in the world where there are so many events every night that you always see men looking handsome in black tie and women in evening gowns.

What are the best and worst things about the city?

The best is the weather: when it’s very cold and the sky is blue. The worst is

the traffic.

Apart from New York, which is your favourite city in the world?

Rome. It’s so chic, the Italians are so delicious and the Romans are divine. You can be walking in a small street and suddenly you find something grandiose in front of you, something out of this world. And the Italians are always in a happy mood. They ask you things with a smile, so you can’t refuse. I love London, too, but I don’t like the weather too much.

Where is your favorite place to go on holiday?

Patmos in Greece. We stay with our great friend [interior designer] John Stefanidis, who has a lovely house there. The island is really beautiful, and not so crowded.

How often do you visit Caracas, where you were brought up?

I haven’t been in a long time. I love my country, and I would love to be there all the time, but we became a left-wing country. It’s difficult. Our family house is still there – it was built in 1590 and has always been in the hands of the same family – but we don’t live there any more.

What is the key to looking well-dressed?

Your clothes have to fit properly. You can be in the most beautiful dress in the world, but if it doesn’t fit, it’s a mistake. Sometimes women say, “I want to look sexy”, and for them, sexy is three sizes too small. That’s also a mistake.

You’re a regular on the best-dressed lists. Do such things matter?

It’s very flattering, and it’s very nice of people to say that you are well-dressed, but you cannot think about it all day long.

What is the biggest mistake celebrities make when dressing for the

red carpet?

They wear clothes that don’t fit or don’t suit them. And their shoes are three sizes too big, because they’re on loan.

You have had a long working relationship with Renée Zellweger. How important to a brand is celebrity endorsement?

Renée is great because she doesn’t use a stylist. She comes to me and we discuss what she wants. She knows exactly what she likes, and that’s very rare.

Who in the public eye would you like to wear your clothes? The Duchess of Cambridge, perhaps?

Well, why not? Of course! She has a fantastic figure and she is always properly dressed for her role. I know some people say she’s too serious, but what they don’t realize is that she is representing something.

Is it true that you can get ready for a black-tie ball in ten minutes?

I can get ready for anything in ten minutes. In my mother’s time it was very different, because none of them worked. These women today who take two hours to get dressed – what are they doing after the first 10 or 15 minutes? If I had to spend two hours getting dressed, I’d be so tired by the time I arrived at the party I’d want to go home.

You’re 76. Are you ever tempted to retire?

No, I adore my work. Nobody’s forcing me to do this.

Two of your four daughters work for your company. Does that ever

cause friction?

It’s fun to work with both of them because they have a different approach to what they do and a different eye. They both have a lot of style, but they’re different. Carolina lives in Madrid and is responsible for the perfumes. Patricia lives in New York and is on my design team.

Do they find it difficult to combine working with motherhood?

No. They are very well-organized. To be a working mother

you have to have a lot of discipline and some help.

Did you ever struggle to combine work and home life?

No, never, because I stop talking about work the moment

I leave the office.

Do you burn the midnight oil at the office?

No. If you can’t do what you have to do between 9am and 5pm then there’s either something wrong with you, or something wrong with the organization.

Can women have it all?

Yes. Women are very lucky because we can do many things at the same time.

Men can’t.

You dressed Jackie Onassis in the last decade of her life. Is her style

still current?

Look at photographs of her now: she looks so modern. She was an amazing woman, so cultivated and intelligent, and a great inspiration for me. I have dressed Michelle Obama, too, and she has a different style to Jackie. She mixes it up a lot and wears a lot of young designers. She has created her own style: more informal I suppose. But the world is getting less formal.

What is the most important thing a woman should have in her closet?

A full-length mirror.

Do you find yourself looking backwards now, rather than forwards?

I like the future much more than the past. If you just sit and think about the past, you’re lost.

Have you made any concessions to age in the way you dress?

Of course. Sometimes you see a woman with a fantastic figure in a mini-skirt, and when she turns around she’s ancient. That doesn’t look right to me. You need to be soigné – or at least more soigné than you were when you were 20. The key thing is to dress according to your age, your style and your figure. It doesn’t matter if something’s fashionable or not – if it looks good, wear it.

Does your husband notice what you’re wearing?

Yes and that’s great, because he has a very good eye and he’s not going to lie to me.

You’ve been married for 46 years. What is the secret of a happy marriage?

Love, respect, friendship and a sense of humor. You have to be able to

laugh together.

If you had your time again, what would you change?

I wouldn’t change anything. I would do it all exactly the same way. Even

the mistakes.

When and where were you happiest?

When I had my first child. I loved it. It’s a fantastic experience.

What advice would you give to a fashion designer starting out today?

Love what you’re doing, believe in it, find your own style and like fashion a lot. Nobody knows what fashion is. It’s a mystery.

Images by Conde Nast Archive/Corbis, Christopher Little/Corbis, Alexis Rodrigues-Duarte/Corbis, Bettman/Corbis

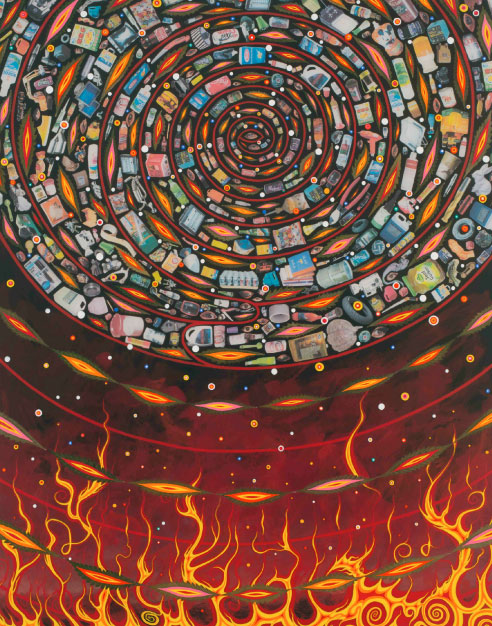

The New York-based Fred Tomaselli is acutely aware that as an artist – particularly one who makes a very comfortable living as such – he is privileged to enter his own little world every time he steps foot inside his Brooklyn studio, even as the world outside seems to be spinning out of control. “The studio is almost like paradise,” the 58-year-old California native says. But he is also a self-described news junkie, reading The New York Times, checking the web and listening to the radio. “The news is constantly penetrating the environment I live in.”

That tension – utopia versus cold, hard reality – pervades Tomaselli’s oeuvre. In his intricately patterned, obsessively assembled – or, as he says, “relentlessly handmade” – “hybrids” of collage and painting, he seems alternately to be inviting the world in and shutting it out. There are elegant, unabashedly beautiful images of birds, but look closer and see that they comprise tiny pictures snipped from magazines; there are fish, trees and flowers fashioned not only from paint but from pills and organic matter like insects and leaves, encased in layers of resin. The New York Times art critic Ken Johnson has compared his hybrids to “windows into the mind of someone in a state of visionary rapture”.

At first glance, his subjects might look placid. On careful inspection, they can veer to the violent: is the bird with its beak thrust into the snake’s mouth in Penetrators (Large), overleaf, feeding the serpent or fighting it? Has the eagle in Avian Flower Serpent just killed the snake wrapped around the tree branch?

Although he lives in Williamsburg, an urban hub of creative types, Tomaselli is actively connected to nature. He is an avid bird-watcher, fly fisherman, surfer and gardener. But his art historical influences also run deep and are as disparate as Japanese Edo prints and Joan Miró’s Constellations series of cosmic-themed paintings, executed at the outbreak of World War II. “I felt like Miró was saying the world is going to hell, but this need for culture continues,” says Tomaselli. “Art needs to be made.”

Tomaselli’s ongoing series, The Times, in which he alters the lead photo on the The New York Times front page, is in the same political vein. He has tweaked images of Ponzi-villain Bernie Madoff, bombed rubble in Syria and children sledding in Central Park. “I decided to become another editor and impose my subjective decisions,” he says. Lawrence Weschler, a well-known cultural critic, has described the series as an “act of witness, a Book of Days across an age of tumultuous transition.”

The series, which has heavily influenced his recent hybrids, will be featured in a solo exhibition at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in October, and in California in February 2015. A selection of his bird paintings will also be on view from October to February as part of The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

His dealers, he says, are adept at insulating him from business affairs. At one time, a while back, uncomfortable with the growing commodification of visual art, Tomaselli tried to stop making it. “But I was really unhappy,” he admits. Now, “I’ve made an uneasy peace with it. Few jobs have no dark night of the soul. I do feel I can do anything I want in the studio. That’s incredible.”

Fred Tomaselli: The Times is at Orange County Museum of Art until May 24, 2015. Fred Tomaselli: The Times, by Lawrence Weschler, is published by Prestel

Your address: The St. Regis Washington, D.C.

Nov. 11, 2010, 2010

In this instalment of his series The Times, Tomaselli

took the original photograph of students protesting

tuition hikes in the UK, or, as the artist says,

“anarchists smashing stuff”, and made an abstraction of brightly

colored shards, like an explosion of stained glass

After Oct. 16, 2010, 2014

Tomaselli’s Times pieces sometimes serve as studies for larger

compositions, such as this one, inspired by a photo

of a machine drilling a tunnel for a Swiss rail system.

“There’s this zooming in and zooming out happening,”

he says of the painting, which pairs Earth’s

flaming core with a kaleidoscope of humdrum man-made products