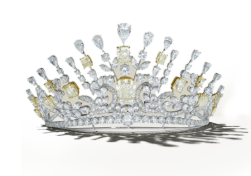

No woman looks bad in a tiara. As designer Vivienne Westwood said: “You can wear rubbish and you can just put [a tiara] on and it does something for your hair.” Hence the tiara’s return to glamorous heads, from the tousled locks of Georgia May Jagger to the regal crown of the Duchess of Cambridge. Although in European royal circles in previous centuries, crowns were daily attire, in the 20th century they were worn only for formal evening occasions, and then only by married women. In the past few years crowns have appeared on every catwalk, from Louis Vuitton to Roberto Cavalli. Why? Partly, specialists say, because of the return of conspicuous displays of wealth in places like China and Russia, and partly because many are extremely good value. A 19th-century tiara, for instance, can be purchased for less than $20,000, and makes a perfect heirloom – particularly those, like the Garrard Tudor Rose collection, that can be dismantled and made into earrings, brooch and pendant. What woman wouldn’t love that? graffdiamonds.com

When hip stylist Camille Bidault Waddington was photographed in her home for French Vogue, she chose to be shot alongside just a few of her favorite things: an antique wooden dresser, a sensuous sculpture and a vase overflowing with bulbous pom-poms of inky-blue hydrangeas. In the past, the hydrangea was a plant that was kept strictly outside. Today, it’s the bloom du jour, not just for stylists, but couturiers, jewellers, hoteliers – and even milliners. At last year’s Kentucky Derby, the heads of fashionable women were adorned with it, clearly inspired by such great hat-makers as Paulette Marchand, who created “caps” of hydrangea blossom for such clients as Greta Garbo and Edith Piaf. “Hydrangeas just go anywhere,” says florist Reed McIlvaine, whose arrangements adorn The St. Regis New York. “In winter we use big white balls of them to recreate snowy scenes, and in fall use them to turn the lobby into a jewelbox of beautiful rich antique colors. They’re incredibly versatile.” rennyandreed.com

Just as men today might compare watches or cars, in 17th-century China the object of desire was a snuff bottle. According to dealer Robert Hall, these miniature bottles were not just objects in which to carry powdered tobacco, but intricately embellished masterpieces, created for China’s elite. Snuff bottles only came to popularity in China because of a ban on smoking tobacco by the rulers of the Qing Dynasty. A bottle that was both portable and watertight became the ultimate vanity object, and exquisite models were created by master craftsmen in materials from porcelain, jade, ivory and coral to wood and glass. Today hundreds of the tiny treasures still make their way into collectors’ hands through organizations such as the Baltimore-based International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society. Their value, too, has soared. In 2010, Bonham’s received one of the biggest ever collections, of 1,700 bottles, which it valued at more than $47m, and in 2011, a bottle delicately painted with a Chinese landscape was sold for a record-breaking $4.17m. e-yaji.com; snuffbottle.com

While many horologists obsess about the movement and complications housed within a watch’s casing, for most watch-lovers, it is the look of a watch that matters most. Hence the trend in the past few years for watch manufacturers to invent increasingly decorative dials. Vacheron Constantin, the world’s oldest watch brand, has led the way by creating what are considered some of the most elaborate and intricate watches ever made. Each of its Métiers d’art collection is not just decorated with a different and highly complicated pattern, but layered with enamel, engraved by master craftsmen and then hand-painted by fine artists. Although the trend for decorative watches is gaining momentum, it dates back more than 500 years to when watches were made using mostly brass or copper and the dials enamelled to make them look more luxurious. In the 21st century, just as in the Middle Ages, designers have realized that, while complications are beloved by aficionados, the one thing no watch-lover can resist is a pretty face. vacheron-constantin.com

For those who didn’t know that wooden surfboards were having a moment, there is plenty of proof online. Such is the devotion of the natural board’s fans that there are now more than 120 websites dedicated to their manufacture. Once the means by which islanders would sail between atolls in the South Seas, wooden boards have become not just the most coveted of surfing equipment, but the most expensive. Master craftsman Roy Stuart recently made the ultimate luxury board, the $1.3m Rampant, its surface hand-painted in gold leaf and finely skimmed in Paulownia. This Asian wood was relatively unknown by surfboard makers until it was used in Australia in the 1980s by the American board-shaper Tom Wegener, who has subsequently become its greatest supporter. Not only is the Asian wood lighter than balsa, it is also more resistant to salt water than any other wood. Today, inspired by the ancient alaia boards in Hawaii’s Bishop Museum – often more than six feet long, finless and only half an inch thick – Wegener has created the finest, lightest waveriders ever created. driftwoodsurfboards.co.uk

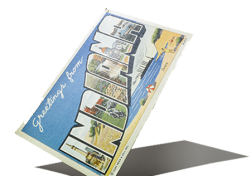

One might have imagined that the postcard would have died a death in the internet age. But there’s a growing trend for cool types to send “retro” postcards, according to Katherine Hamilton-Smith, director of cultural services at the Lake County Discovery Museum in Chicago, which holds the Curt Teich Postcard Archives, the world’s largest public collection of postcards. Cards have become collectable: the work of John Hinde’s studio is highly sought after, as are works by historic postcard artists such as New York-born Ellen Clapsaddle and Australia’s Ida Outhwaite. Far from destroying the postcard, the internet has attempted to emulate its essence. The first

e-postcard site, The Electric Postcard, was created in 1994 at the MIT Media Lab, and since then apps such as Postcard on the Run and Postagram have been invented that convert messages into physical cards. But even with this innovative technology, old-fashioned postcards will never die out, says Hamilton-Smith. “They’re both

a tiny physical gift and a message; evidence that someone somewhere is thinking of you.” teicharchives.org